During World War II, raw materials were in short supply. Wool was needed for military uniforms and a shortage of rubber led to the near disappearance of athletic shoes. Silk stockings vanished, as silk fiber was needed in the production of parachutes. Additionally, factories which had produced civilian clothing were reconfigured to produce items needed in the war effort. In order to regulate the remaining production of civilian garments, the United States government implemented the L-85 regulations in 1942. L-85 dictated the styling of garments with an eye to conserving materials and production time. Skirt length, hem width and types of trim were strictly regulated, as were the cuffs and pockets of menswear. Home-sewn clothing was exempt from these regulations, but all were encouraged to “make do and mend.”

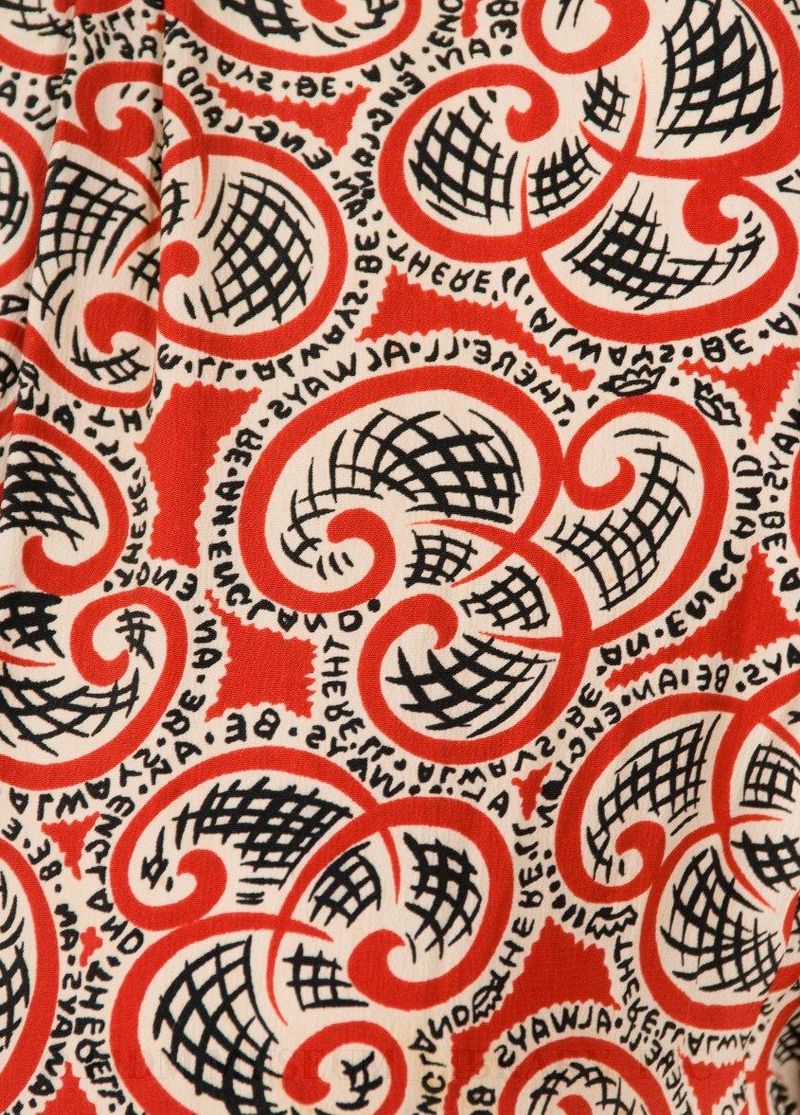

In addition to the actual conservation of materials, L-85 regulations provided a constant visual reminder of the necessity of total participation in the war effort. The production of propaganda textiles featuring slogans and imagery relating to the war allowed civilians to support the war effort in yet another way. Interestingly, these textiles were not produced by governments, but by independent manufacturers. In the United States and Britain, propaganda textiles featured familiar slogans such as “V for Victory” and “Keep it Under Your Hat,” a reminder that casual conversations could inadvertently reveal confidential information. Other designs featured brightly colored patterns of red, white and blue, the colors of the Allied flags. The FIDM Museum propaganda textile dress seen below features a red, white and blue pattern with the slogan “There’ll Always be an England,” after a patriotic 1939 song.

Dress

1941-42

Gift of Madge Baker

2005.842.2

The textile seen here was among a collection of propaganda textiles manufactured and sold in March 1941 as a fund-raiser for the British-American Ambulance Corps, a New York based volunteer ambulance corps. In March 1941, the United States had not yet entered the war, so the textiles were intended to provide moral and financial support to a beleaguered Britain. Other featured slogans included “Bravo Britain” and “Friends Across the Sea,” in colors called English Channel blue and Buckingham Palace red. To promote the textiles, which were marketed nationally, a fashion show was held in Manhattan featuring socialites clad in dresses created from the various textiles. Astute readers probably noticed that the text in the detail image appears backwards. This collection of textiles was intentionally printed with “mirror-writing” which could be read properly only when reversed.

With its square shoulders and slightly full, just-below-the-knee skirt, this dress showcases all important elements of World War II era fashions. The prevalence of military uniforms, L-85 regulations and a sense of patriotic duty led to dresses with a compact, structured silhouette similar to that of a military uniform. The ruched, self-fabric trim at the shoulders and waist, along with the fullness of the skirt suggest that this was made soon after the textile was released in 1941. With the advent of L-85 regulations in 1942, even home-sewers probably would have streamlined their garments out of a sense of patriotic duty.

Further reading

Atkins, Jacqueline, ed. Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States, 1931-1945. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

Wolford, Jonathan. Forties Fashion: From Siren Suits to the New Look. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2008.

The subtle text detail is really neat! From a distance it just looks like an ordinary print with no hidden message at all, but once you get up close the details are revealed.

Yes, detail is key to the success of this print. What we in the museum still can’t quite figure out is why the text is reversed. Based on documentary evidence, it was clearly intentional, but what purpose did it serve?

I’ve seen other prints in the past that had reversed text in them, but never got a definite explanation as to why. I always wondered if it was so the wearer of the garment would be able to read the text in the mirror. Since the woman wearing the dress would be the one most likely to view it up close, maybe it’s a morale thing. She stops to check her appearance in the mirror, and there it is, a subtle reminder that “there’ll always be an England.”

I actually own a BAAC fabric clutch in a brown colorway with leather trim. The brown could be a faded red (brown’s not very patriotic) although the clutch has no other flaws. The curlicues in the print spell BAAC. Do you have any other of the British-American Ambulance Corps fabrics in your collection?

Wow! This dress is the only BAAC textile in our collection. There are certainly other examples out there, but I’ve only seen print references, not images of the actual textile. Does your clutch have a manufacturer’s tag?

I have a dress that I believe is BAAC, it shows the monogram of George VI. I’ll have to check the inside, I know there is some writing there. Bought it about ten years ago to wear to a 1940’s dance.