Paper fan

Paper fan

Spain

1875-1899

Gift of Yvonne Hummel

2010.947.10

Folding fans printed or painted with Spanish genre scenes of bullfighters and dancers are relatively common in museum collections. They generally date from the second half of the nineteenth century and are typically very large. When open, the fan above is 26 inches from point to point of the fan guards, the outermost spines. An 1897 article in Godey's Magazine noted this characteristic of Spanish fans, describing them as "extremely large and usually black" and decorated with amusing scenes of Spanish life.1 The fan pictured above features indoor and outdoor views of a festive occasion, similar to the Spanish fans described in Godey's Magazine. If the image itself didn't give away its origin, the fan is also labelled "Madrid" in applied gilt lettering.

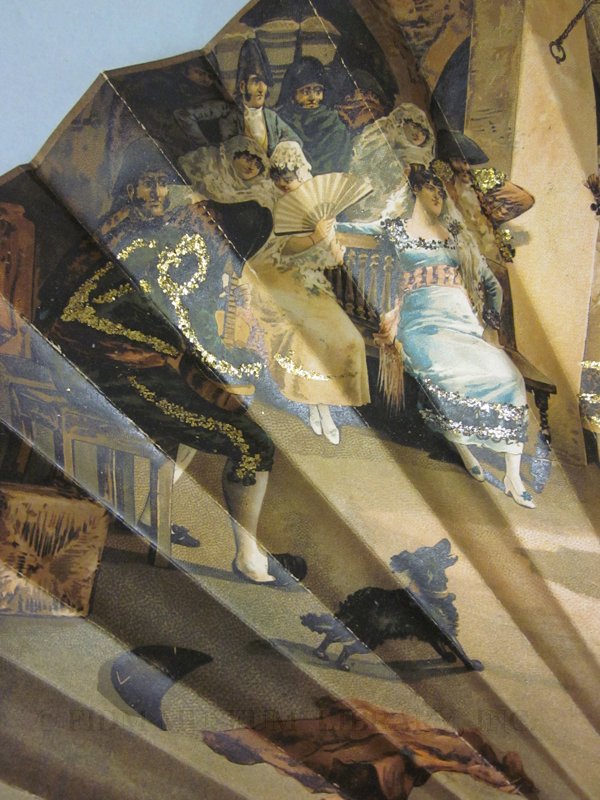

This detail image shows the central dance scene pictured on the fan above. Note that the central figure is a woman holding a large fan.

2010.947.10 Image detail (center)

2010.947.10 Image detail (center)

This detail portrays the far left portion of the fan. Notice the seated woman holding a fan.

2010.947.10 Image detail (far left)

2010.947.10 Image detail (far left)

The vogue for Spanish folding fans has roots in a seemingly unrelated event: Napoleon's Spanish campaigns. From 1807/8 until his abdication in 1814, Napoleon occupied areas of modern-day Spain and Portugal as part of his bid to expand French influence. Prior to Napoleon's occupation, Spanish art was rare in other parts of Europe. This changed with Napoleon's Spanish campaigns, which sparked hispagnolisme, an interest in Spanish art and culture that influenced France throughout the nineteenth century. In 1838, King Louis Philip dedicated a gallery at the Louvre to Spanish art, allowing many French artists the opportunity to see Spanish art (primarily painting) in person. Because of North America's reliance on France for cultural leadership during, nineteenth century American artists also became interested in Spain.

The importance of Spain is evident in the large numbers of nineteenth century French and American paintings that portray aspects of Spanish life and culture. Édouard Manet, John Singer-Sargent, Edgar Degas, William Merritt Chase and other well-known artists were influenced by the work of Spanish painters Francisco de Goya and Velázquez. Paintings by these French and American artists often portray stereotypical aspects of Spanish culture, including bullfighting or the performing arts. Manet's painting A Matador portrays a Spanish bullfighter gesturing to an unseen audience while his Lola de Valence pictures a Spanish dancer named Lola Melea. Melea was the star performer in a troupe of Spanish dancers who performed La Flor de Sevilla (The Flower of Seville) from August to November 1862 in Paris. Chase and Singer-Sargent painted a hired Spanish dancer in perform in Chase's Paris studio sometime in 1890. The resulting paintings are similar, though Singer-Sargent's La Carmencita stands still, while Chase's Carmencita is captured mid-dance.

Folding fan

Folding fan

1870-1889

Spain

Gift of Yvonne Hummel

2010.947.6

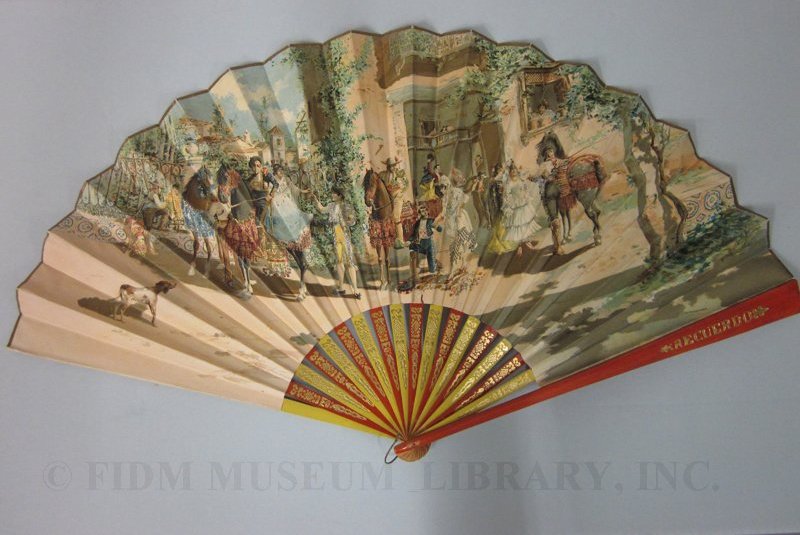

Also large, the fan above captures a tranquil moment. A small group, including a matador, enjoys a musical interlude. This image fades into cityscape with bridge. Any guesses as to the city portrayed? The reverse is a print of repeating checkered squares and roses.

The influence of Spain appeared in realms other than romanticized genre paintings. After Napoleon's attempts to capture Spain failed, the country became a popular destination for rugged travellers. According to an 1875 travelogue, Spain offered "strong and sharp contrasts" for the North American traveller.3 Spanish art and architecture tours, a variation on the Grand Tour, left regularly from Paris and London. A romanticized version of Spain appeared in the popular opera Carmen, which portrayed a love triangle anchored by the Spanish gypsy Carmen. The opera premiered in 1875, but was staged to even greater acclaim in 1881.

The popularity of the French Empress Eugénie also brought attention to Spain. Spanish by birth, educated in Paris, Empress Eugénie was the wife of Napoleon III. During her 1853-1871 reign as Empress, Eugénie was the world-leader in fashion, setting trends copied throughout the Western world. In September 1855, Godey's Lady's Book described Eugénie as the "closest devotee of fashion…the only woman in the world compelled to wear a new dress on every appearance." A later article, written after the death of her husband and son, described Eugénie as "the most brilliant and conspicuous princess in Europe. She set the fashions for the world."2 Though nothing about her personal style was overtly Spanish, her public stature certainly brought attention to Spanish culture.

According to fashion periodicals, garments and accessories were given names related to Spain. On February 22, 1873, Harper's Bazaar featured a brief article on Spanish hair combs, recommending them for wear with full evening dress. For the most part, items associated with Spain were accessories or small touches that added an aura of romantic exoticism to everyday dress. This attitude towards Spanish culture is exemplified in an 1872 article on the color red, which praised the Spanish woman's supposed habit of wearing a red rose behind the ear. This image could easily have been drawn from many of the paintings discussed previously.

How do Spanish folding fans fit into this mania for all things Spanish? By the beginning of the nineteenth century, folding fans were already established as both a fashionable accessory and commemorative device. Fashion fans coordinated with dress styles, while commemorative fans were used to relay information about political and national events or the births or deaths of famous (often royal) people. Small, decorative and functional, fans also became popular as souvenirs during the nineteenth century. For those who could travel abroad, fans were an easily portable souvenir for friends and family at home. Some fans might have purchased at one of the many international expositions held during the nineteenth century. National pavilions at international expositions often sold souvenir fans, whether or not the fan was a traditional part of the culture represented. Such fans might feature the date and name of the exposition, or imagery related to the culture of the exhibitor. A recent post on our blog examined fashion at the Paris Exposition of 1900.

Spain was a participant in many international expositions. According to Harper's Bazaar, Spanish bullfights were a popular attraction at the 1889 Exposition Universelle. Outfits worn by the toreadors inspired Parisian women to wear gowns of "Spanish red cloth."4 Several months later, Harper's Bazaar described the Spanish jacket. Modelled on a toreador jacket, the Spanish jacket was short and trimmed with tassels, beading or fringe.

Many extant Spanish folding fans are inscribed or stamped with the name of a Spanish city. This suggests a calculated intent to link fans to a specific national origin. The fan below reads "Recuerdo de Espana," or souvenir of Spain. "Recuerdo" is printed on one fan guard, "de Espana" on the other. The fan seen at the beginning of this post reads "Recuerdo de Madrid." Though sources indicate that fans were widely used in Spain, logic suggests that fans for domestic consumption wouldn't require such an obvious marker of nationality. Additionally, the romantic imagery presented on Spanish paper fans suggests that they were tailored to adhere to external perceptions of Spanish culture.

Folding fan

Folding fan

1875-1899

Gift of Yvonne Hummel

2010.947.7

Though we don't know when or where our Spanish fans were purchased, they are clearly situated within a cultural context which venerated romanticized aspects of Spanish life. Like orientalism, hispagnolisme created a fictionalized version of Spanish culture signified by exotic difference: bullfighters, red roses worn behind the ear and dancing girls. This perception of Spain circulated on multiple economic levels. Those with access and the means could attend museum exhibitions to see French or American genre paintings portraying Spanish life. Consumers with lesser means could purchase a Spanish-themed folding fan. The idea of Spain suggested by Spanish fans might not be accurate or true to real life, but the appeal is obvious. Romantic, festive and visually rich, it offered an appealing respite from the day-to-day repetition of real life.

2010.947.7 Detail (right of center)

2010.947.7 Detail (right of center)

1 "Fans." Godey's Magazine. June 1897: 662.

2 "The Ex-Empress Eugenie." The Youth's Companion. 17 Mar. 1881: 100.

3 "Spanish Sketches." Scribner's Monthly. Dec. 1875: 213.

4 "New York Fashions." Harper's Bazaar. 7 Dec. 1889: 883.