The FIDM Museum blog will be on hiatus through early January 2015. In the meantime, enjoy weekly posts from the archives. To keep up with our current projects, find us on Facebook and Twitter, which will be updated regularly during the blog hiatus. This post on Mariano Fortuny was originally published in 2011.

**********

Though Mariano Fortuny (1871-1949) is remembered primarily for his finely pleated silk gowns, it would be inaccurate to categorize his work as fashion, i.e. undergoing frequent stylistic changes. Unlike a couturier, who regularly introduces new silhouettes, colors and textiles, Fortuny produced essentially the same garment (with slight variations) from 1909-1949. During and before this period, Fortuny was also an active painter and inventor who designed an innovative new system of indirect lighting for theatrical productions. Because of Fortuny's disinterest in the cycle of fashion, and his career as a painter, he is often considered an artist who made clothing.

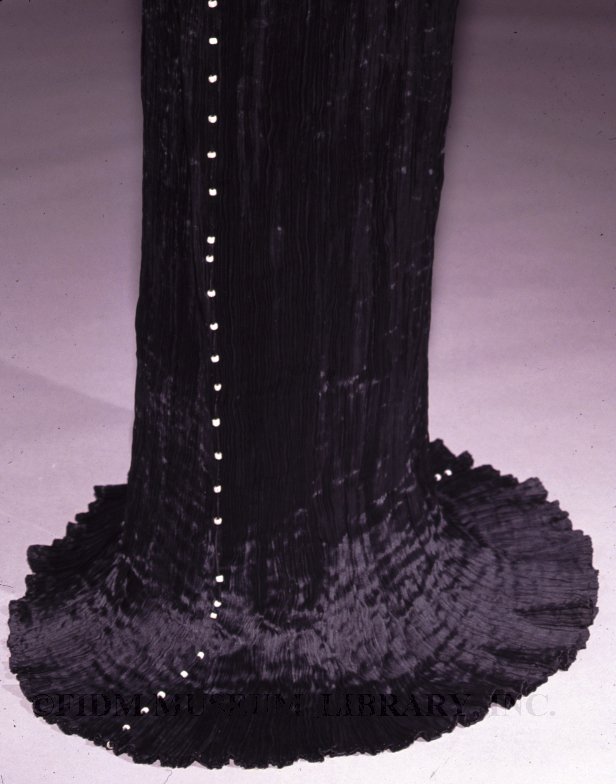

Fortuny's trademark dress is the Delphos, a simple column of finely pleated silk. As suggested by its name, which is both a location in Greece and the son of the Greek god Apollo, the Delphos dress is based on ancient Greek dress. Specifically, the Delphos and its variations resemble the pleated garments portrayed in Greek and Roman art. Though Fortuny was personally interested in Classical antiquity, this interest was also shared by many thinkers of his generation. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a widespread interest in the ideals and perceived virtue of ancient Greece and Rome. In terms of fashion, this was expressed as an interest in looser, rational and/or Artistic dress styles.

Mariano Fortuny

Mariano Fortuny

c. 1925

Silk charmeuse

FIDM Purchase

80.1925.059.4 (waist detail)

A Delphos is made from 4-5 panels of pleated silk; each panel is about 37 inches wide. The side seams are embellished with small glass beads, which are both functional and decorative. The beads are strung on a narrow silk cord, which is then stitched to the side seams. The delicate beads help weigh down the extremely lightweight fabric of the dress, pulling it closer to the body. Fortuny always used glass beads produced by the famous Murano glassworks, which was near his home in Venice. Fortuny's dresses were designed to glide over the body, showcasing the beauty of the natural form. All Fortuny garments were one-size-fits all, though a drawstring at the bateau neckline and the addition of fabric sashes allowed wearers to customize the fit.

The sash seen in the image above is typical of those worn with the Delphos. It also showcases another of Fortuny's talents, textiles printed in patterns inspired by a variety of historic cultures. Capes, cloaks and jackets of Fortuny-printed silk velvet were frequently worn over the solid-color silk Delphos or used to create simple, unfitted gowns. Our Delphos is black, but Fortuny also utilized other colors and shades. Most often, these are rich, nearly luminous jewel tones. Fortuny always dyed his own fabric, often with the help of his wife Henriette.

Fortuny's Delphos was introduced about 1909, when the highly artificial S-bend silhouette was dominant. Fortuny's lightweight creations were meant to be worn without any corsetry, and ideally, with only the bare minimum of undergarments. Because of this, Fortuny's early experimentation in classically-influenced dress were worn only by the most daring of women, including dancers Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, actress Lillian Gish and the noted eccentric Marchesa Luisa Casati. Gradually, Fortuny's gowns were adopted as at-home dress by some women. In the fashion press, they were often referred to as a teagown, a style of at-home dress popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By the 1920s, Fortuny's Delphos and its variations were becoming acceptable for wear outside the home.

The aspect of Fortuny's work that receives the most attention is the narrow pleats that give the garments their textural character. Silk, which Fortuny used to create his pleated gowns, is notoriously difficult to permanently pleat. Using a secret process that he invented, Fortuny was somehow able to achieve a nearly permanent pleat. The panels of fabric were probably finger-pleated when wet, and then heat-set. The only evidence of the process is an image taken from a patent application for a machine used for some part of the process. Scholars have suggested that the pleated widths of fabric were held in place by thread during the heat-set process. The panels, each containing between 430-450 pleats, were hand-sewn after pleating.

Though Fortuny's pleating process created a very stable pleat, customers were encouraged to maintain their pleated Fortuny garments by storing them inside small, round hat-boxes. In the boxes, the dresses were stored in a twisted coil which helped maintain the pleats. If the pleats started to come undone due to water damage or extended sitting, Fortuny would re-pleat the gown for free at his Venice production facility. Upon Fortuny's death in 1949, production of his distinct pleated garments ceased.

Women who wore Fortuny's creations were devoted customers. Photographic evidence suggests that many women lovingly maintained their Fortuny garments for decades, either as collectibles or garments still worn in regular rotation. Even today, women occasionally wear a Fortuny creation to a red-carpet or gala event. Have you spotted a Fortuny out and about lately?

It’s lovely!

I’ve always wondered how these dresses were cleaned. From what is said about water damage, I assume they were not washed. But if they were worn with minimal underwear, they would need frequent cleaning, as modern dresses do. Were they dry-cleaned? Would the pleats stand up to that?

Great question, Clare! The pleats would definitely not stand up to water, but because dry cleaning processes were so different in the early 20th century, it’s difficult to say if it would have been safe. I was not able to find any original cleaning instructions, but there is evidence that some cutomers sent their dresses back to the Fortuny atelier for repleating after cleaning, or when the pleats began to loosen from wear. I hope that helps!