“There is a new ‘wrinkle’ in dresses. As a matter of fact, they are all wrinkles, for they are made from the pretty crêpe tissue paper…”[1]

The use of paper in fashion has a long history, spanning centuries and civilizations across the globe. Yet the introduction of crêpe tissue paper in the late 19th century sparked a new interest in the endless possibilities of this fabric-like fiber. Already a popular material for making artificial flowers and home décor, tissue paper was first given its machine-made crinkle by an English manufacturing company in the late 1880s.[2] Massachusetts paper goods company Dennison Manufacturing added imported crêpe paper in a vivid array of colors to their list of offerings around 1892; the company eventually went on to produce their own crêpe paper lines in 1914.[3] Recognizing the artistic promise of tissue and crêpe paper, Dennison’s created a specialized Art Department that provided in-store craft demonstrations and published instructional pamphlets.

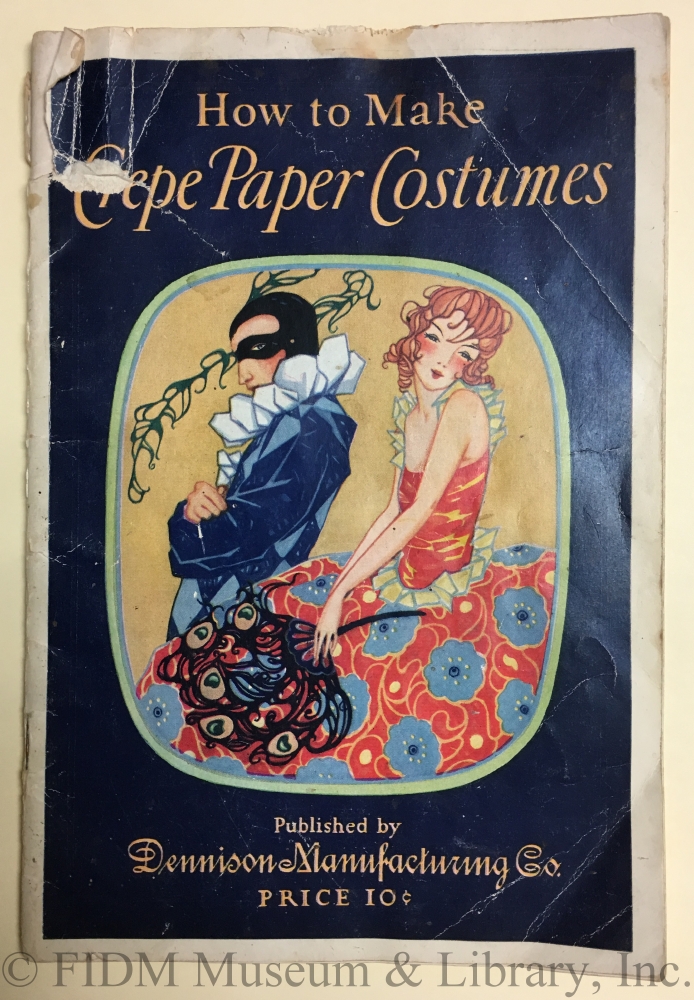

Booklet

How to Make Crepe Paper Costumes

Dennison Manufacturing Co., 1925

Gift of Ron Bernstein, SC2011.1145.2

By the turn of the century, crêpe paper became a fashionable material for all manner of crafts: dressing table accessories for the boudoir, cotillion favors, lampshades, and party décor. Harper’s Bazaar touted the ease of braiding crêpe paper to make sturdy accessories like sewing bags and even bedroom slippers.[4] The magazine also recommended a more unusual use: adding a sheet of rose crêpe paper to the wash to restore the color of a faded pink blouse![5]

Girl’s crêpe paper flower costume in Art and Decoration in Crepe and Tissue Paper, Dennison Manufacturing Co., 1917, via hathitrust.org.

The novelty material was similar to a woven textile such as cotton gauze or silk georgette, allowing the possibility that “any pretty evening frock can be copied in the crêpe.”[6] Consumers quickly realized crêpe paper was strong enough to fashion fans, hats, parasols, bags, and even garments; it was particularly suitable for fancy dress ensembles, as the wearer could make an outlandish costume for a fraction of the cost. Starting in the 1890s and continuing throughout the early 20th century, crêpe paper costume parties for both adults and children became a popular amusement.[7]

Child’s fancy dress costume: dress and fan

Crêpe paper, 1920s

Gift of Steven Porterfield, SC2014.897.27AB

Child’s fancy dress costume: dress and hat

Crêpe paper, c. 1910-1915

Gift of Manlove Family, 2006.870.37AB

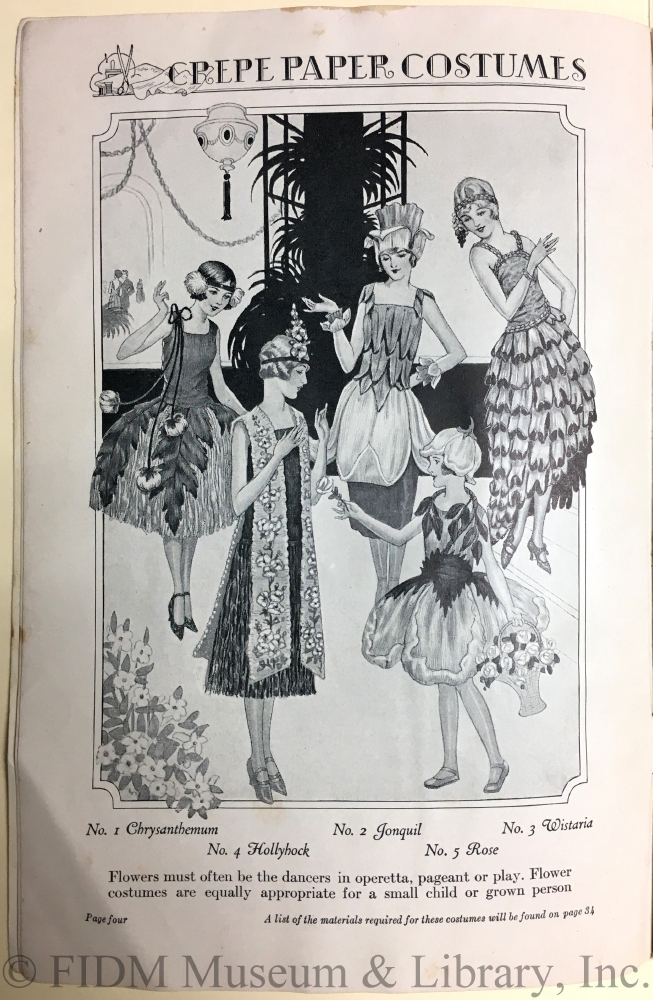

Children’s fancy dress parties, inspired by the masquerade balls adults had participated in for centuries, were introduced in the mid-19th century, and rose in popularity after Queen Victoria and Prince Albert held a costume party for their children in 1859.[8] Butterflies, harlequins, fairies, storybook characters, and animals were well-loved choices, but for little girls the flower was a perennial favorite. Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar included drawings and instructions on how to make charming roses, lilies, or poppies out of crêpe, and Dennison’s Manufacturing Co. continued to release annual booklets with crêpe costume patterns. The assembly was fairly straightforward, as crêpe paper was strong enough to be sewn directly onto a fitted muslin slip that formed the base of the costume. Crêpe’s unique texture gave a realistic appearance to skirts made of layered petals, demonstrating “what wonders may be accomplished with paper.”[9]

Child’s fancy dress costume

Crêpe paper and fabric flowers, 1920-1925

Gift of Jay E. Hampel, 2008.801.2

Flower costumes from How to Make Crepe Paper Costumes

Dennison Manufacturing Co., 1925

Gift of Ron Bernstein, SC2011.1145.2

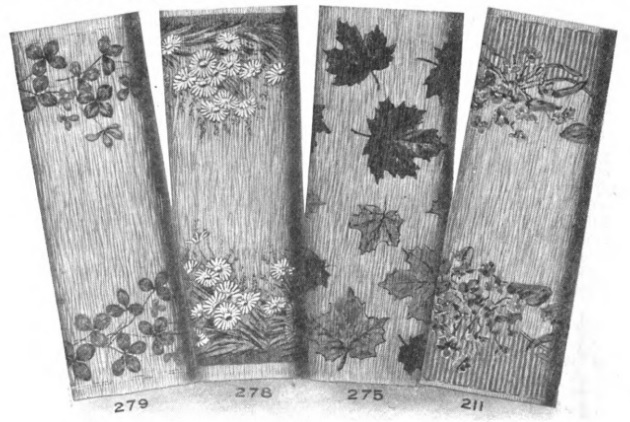

Of course, crêpe was not used exclusively for costumes. A c. 1897 girl’s dress in the FIDM Museum Collection reflects a fashionable children’s style made with crêpe paper sewn to a cotton underdress. At first glance, it is nearly impossible to tell that the garment is paper – the printed pattern of violets on cream crêpe adds to the fabric-like appearance. Though difficult to maintain over multiple wears, a child’s garment would eventually be outgrown; crêpe was a clever solution to providing new frocks at an affordable price.[10]

Girl’s dress

Crêpe paper and cotton, c. 1897

Gift of Steven Porterfield, 2007.897.3

Printed crêpe paper selections in Art and Decoration in Crepe and Tissue Paper, Dennison Manufacturing Co., 1917, via hathitrust.org.

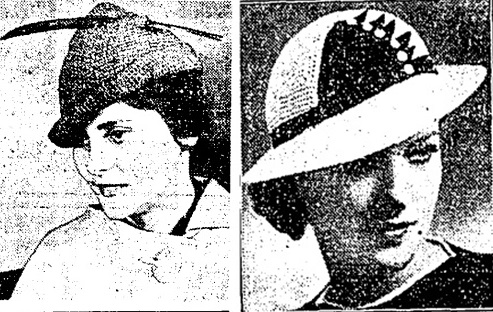

The low price point of crêpe paper led to its resurgence as a stylish material for accessories in the 1930s. During the global economic depression, women turned to inexpensive accessories to update and enliven their wardrobes when new garments could not be purchased or sewn.[11] Newspapers advising savvy readers on how to stay fashionable on a budget celebrated the “practical and wearable”[12] attributes of twisted crêpe paper, which promised to hold up in the rain, survive a strong scrub brush, and give the appearance of expensive straw. Outfits were bestowed new life with a crocheted crêpe paper hat, jabot, handbag, or belt – so thrifty and easy to make, readers were encouraged to whip up “one for each dress.”[13]

Crocheted crêpe paper hats. Left: Los Angeles Times, April 9, 1935 (A9), Right: Los Angeles Times, May 29, 1936 (A8)

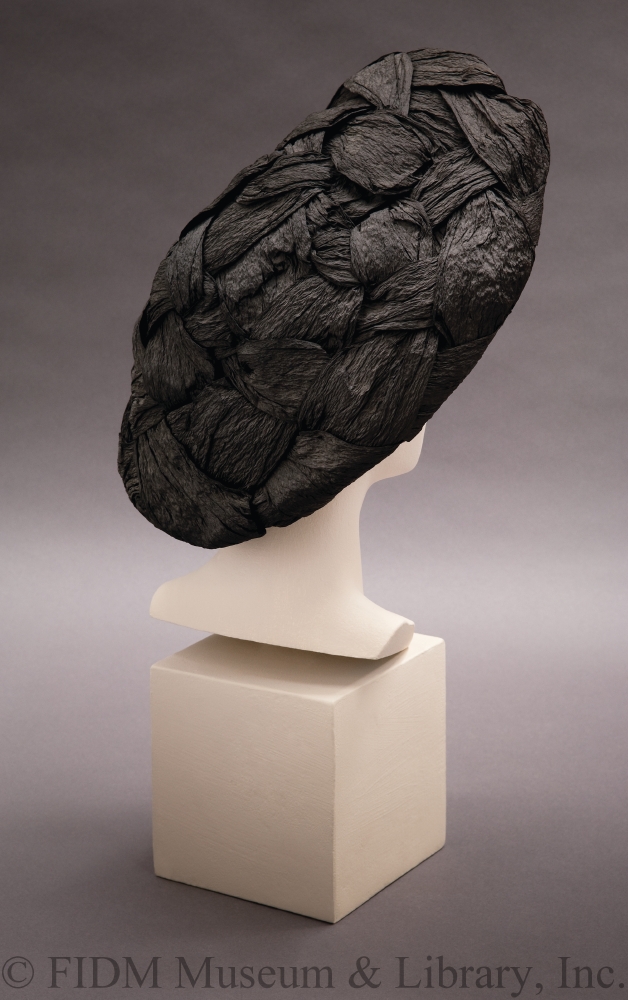

The ingenuity of depression-era fashion continued into the 1940s during WWII, as the scarcity of materials and government-mandated fabric restrictions encouraged creativity in clothing. Much like the 1930s, fashion advice focused on adding accessories to liven up a tired ensemble, with hats in particular being “the best source for a bit of wartime novelty.”[14] The Parisians had long set the bar for exquisite millinery, producing styles that inspired the rest of the world every season; now, their skills were put to the test as shortages abounded in their occupied city. Not to be deterred, milliners used every cast-off scrap to create innovative headwear – maintaining the elegance and integrity of Parisian fashion became an act of subtle defiance against their intruders.[15] Wood-shavings, twine, newspaper and yes, even crêpe paper became viable resources to construct a new chapeau, such as the 1942 black bowl-shaped crêpe hat in the FIDM Museum Collection by French milliner Rose Valois (active 1927 – 1970). The hat’s natural fiber – often the only material available – and woven pattern follow similar Rose Valois designs from the same period. The millinery house, founded by three women, had a unique connection to the war; not only did they set to work making caps for the nurses of the American Hospital in 1939,[16] but one of its original partners, Vera Leigh, left the business to join Britain’s Special Operations Executive in 1940.[17]

Hat

Crêpe paper

Rose Valois, French

FIDM Museum Purchase, 2003.5.33

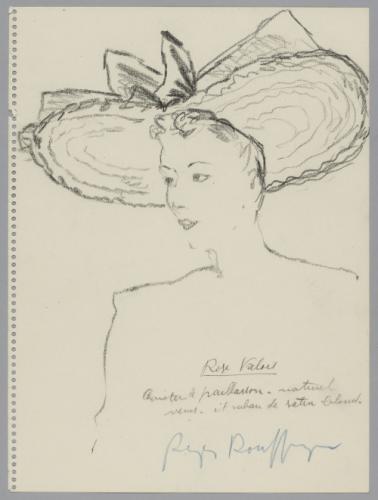

“Rose Valois natural fiber hat”

Illustration by Roger Rouffiange, 1942

Palais Galliera, 1980.55.14.64

From fancy dress frivolities to economical accessories, novelty party décor to defiant wartime resourcefulness, the 130 year history of crêpe paper has produced creative fashion at its finest. As designers continue to experiment with the unique qualities of crêpe paper, the prediction of a 1894 newspaper article promoting the benefits of the new material rings true: “Necessity is no longer the best mother of invention. Ingenuity has usurped the throne.”[18]

[1] Eleanor Dumfries, “Paper Frocks: Pretty Fancy Dresses Made of the Improved Crepe Paper,” Los Angeles Times, November 25, 1894, 20.

[2] Seventy-Five Years: 1844-1919 (Framingham: Dennison Manufacturing Company, 1920), 45. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=bc.ark:/13960/t84j1b084;view=1up;seq=1

[3] Ibid.

[4] M.B. de Rennes, “Gifts of Braided Crepe Paper,” Harper’s Bazar, December 1912, 616.

[5] “Pin-Money Frocks,” Harper’s Bazar, April 1916, 77.

[6] Dumfries, “Paper Frocks,” Los Angeles Times, November 25, 1894, 20

[7] “A Crepe-Paper Party,” Harper’s Bazar, July 17, 1897, 596.

[8] “Fashion Plate – Fancy Ball Dresses for Children,” V&A Museum, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O36454/fancy-ball-dresses-for-children-fashion-plate-unknown/.

[9] “Seen in the Shops,” Vogue, February 12, 1910, 18.

[10] Kevin Jones and Christina Johnson, Fabulous (Los Angeles: FIDM Museum Press, 2011), 143.

[11] Colleen Hill, “Great Chic from Little Details Grows: Women’s Accessories in the 1930s,” in Elegance in an Age of Crisis, eds. Patricia Mears and G Bruce Boyer (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2014), 223.

[12] “Crocheting Hats with Crepe Paper,” The Washington Post, August 11, 1933, 9.

[13] “Gifts to be Made at Home Range from Smart Knitted Dresses to Box Pillows,” The Washington Post, November 19, 1933, AM10.

[14] Jonathan Walford, Forties Fashion: From Siren Suits to the New Look (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2008), 97.

[15] Jones and Johnson, Fabulous, 211.

[16] “The Pulse of Fashion,” Haper’s Bazaar, November 1939, 49.

[17] Anne Sebba, Les Parisiennes: Resistance, Collaboration, and the Women of Paris Under Nazi Occupation (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2017), 167.

[18] Dumfries, “Paper Frocks,” Los Angeles Times, November 25, 1894, 20