Look closely at any 18th or 19th European century painting depicting court life – chances are, there is a woman somewhere in the vignette artfully displaying an ornate fan. It is an accessory that we rarely think of today, yet just one hundred years ago, a lady was rarely seen without it. So ubiquitous was the fan that in 1711 author Joseph Addison wrote in The Spectator, a popular British magazine, “Women are armed with Fans as Men with Swords, and sometimes do more Execution with them.”[1]

Jules Donzel fils, artists

France, c. 1900

Painted silk taffeta & bone

2013.975.14AB

Countries such as China, Japan, Egypt, and India used some form of fan – folded, fixed, or brisé – for over five thousand years before Europeans acquired a taste for the novel accessory.[2] France’s King Henri III is credited with introducing the fan to court dress during his reign (1547 – 1559); his mother, Catherine de Medici, is said to have brought fans, perfume, and lace to the French court from Italy.[3] Sixteenth-century trade routes dealing in spices, tobacco, textiles, metals, and furs connected Europe to the rest of the world, thus instigating a period of great cross-cultural influence that included dress.

Jolivet, artist

Tiffany & Co., retailer

Silk taffeta, metallic net, metallic & mother of pearl sequins

2013.975.6AB

Though fans did serve an entirely practical purpose of cooling and keeping bugs at bay, they became a mandatory fashion accessory once it was introduced at the royal court. Not only did a fan advantageously display the delicacy of a woman’s hands, it could also be used as a tool in the silent, complicated diversions of a royal court. It concealed the face to hide emotions and share gossip. A woman could use it flirtatiously to communicate with a suitor, or perhaps a secret lover. The Silent Language of Fans continues to hold a romantic fascination to this day – the hidden meaning of specific gestures that conveyed everything from “I love you” to “I despise you.” Undoubtedly, women used fans as a form of expression; as Addison wrote “There is scarce any emotion in the mind which does not produce a suitable agitation in the Fan.”[4]

Fans were a staple of the European upper class wardrobe for over four hundred years. As modes changed, so too did the fan, growing or decreasing in size and extravagance to match the fashionable silhouette. Furthermore, fans showcased the finest craftsmanship in decorative arts and painting. Made of tortoiseshell, ivory, wood, or mother-of-pearl, the sticks and guards could be intricately carved, inset with gold and silver, or adorned with jewels. Specialized artists painted elaborate scenes on fan leaves made from parchment, leather, vellum, or silk; feathers, sequins, and lace were equally popular. Famous fan makers – Duvelleroy, Félix Alexandre, Tiffany – dedicated themselves to the métier d’éventail, creating magnificent works of art on a miniature scale.

Maison Duvelleroy, retailer

France, 1900-1905

Hand-carved mother-of-pearl and point-de-gaze lace

2016.975.5

Certain themes emerged as popular motifs for scenes depicted on fan leaves. Biblical stories, classical mythology, pastoral landscapes, romantic escapades, and even political propaganda featured prominently across unfurled fans.[5] Just as commemorative merchandise is sold today for royal weddings, births, and coronations, fans celebrating momentous public occasions were eagerly purchased in the 18th and 19th centuries. Souvenir fans marking trips abroad were also common; young British men completing the Grand Tour often brought home fans that showcased famous landmarks of European capitals.

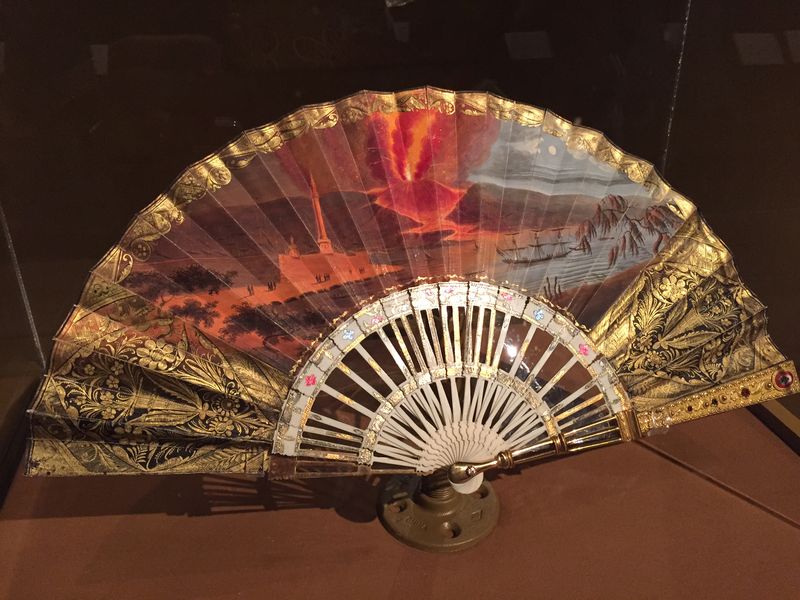

France, c. 1825

Hand-painted parchment, ivory, gilt brass & rhinestones

2016.975.4

One souvenir fan in the FIDM Museum’s exhibition A Graceful Gift: Fans from the Mona Lee Nesseth Collection portrays a dramatic moment in history: the eruption of Mount Vesuvius over Pompeii in AD 79. This tragic event experienced a cultural revival when formal excavation began on the ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum in 1748. Much like the discovery of King Tut’s Tomb in 1922, a phenomenon that sparked the Egyptomania trend in fashion and design, the volcanic eruption became a popular subject for books, paintings, architecture, decorative arts, and accessories. Droves of foreign tourists visited the buried cities and zealously purchased mementos marking their thrilling experience, much like the fan on display in our gallery.[6]

A Graceful Gift: Fans from the Mona Lee Nesseth Collection is open until July 2 – what fan discoveries will you make?

[1] Joseph Addison, The Spectator, No. 102, July, 1711. http://www.bartleby.com/library/prose/55.html.

[2] Valerie Steele, The Fan: Fashion and Femininity Unfolded (New York: Rizzoli, 2002), 10.

[3] Anna Gray Bennett, Unfolding Beauty: The Art of the Fan (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1988), 12.

[4] Joseph Addison, The Spectator, No. 102, July, 1711. http://www.bartleby.com/library/prose/55.html.

[5] Bennett, 14.

[6] Avril Hart and Emma Taylor, Fans (London: V&A Publications, 1998), 66.