“What makes Geoffrey Beene great? Is it the sophistication of his cut that makes the most bulky fabric seem airborne? The curved lines that give a graceful femininity to clothes without dipping into banality? It is all this but, more important, it is the designer’s unceasing struggle to find new materials and new shapes that flatter a woman’s body.”[1]

Photograph by Michel Arnaud

Photograph by Michel Arnaud

Geoffrey Beene at his Spring/Summer 1991 runway presentation

Gift of Arnaud Associates, SC2000.1095.1

Described as cerebral, modernist, and the “architect of American clothing,”[2] designer Geoffrey Beene (1927 – 2004) made an indelible mark on fashion in the 20th century – and his visionary creations influenced how women would dress in the next centennial, too. His journey began as Samuel Albert Bozeman Jr. in Haynesville, Louisiana, where he was born into a family of doctors yet maintained a keen eye for design throughout his childhood. He followed the family tradition and enrolled in medical school at Tulane University – legend has it he sketched Adrian gowns over the figures in his Grey’s Anatomy textbook.[3] Leaving the medical field behind, his family sent him to California to live with an aunt, and a brief stint working with the window displays at I. Magnin in Los Angeles was followed by Traphagan School of Fashion in New York City. However, it was Beene’s time in France that taught him the principles of good design and the art of dressmaking.

Evening gown Image courtesy of Vintage Hamish, Vogue.com

Evening gown Image courtesy of Vintage Hamish, Vogue.com

Geoffrey Beene, 1971

Gift of Lenore Greenberg

89.1977.059.20

Beene moved to Paris in 1948 and experienced the fervor caused by Dior’s famed New Look. Yet it was another designer he credits with opening his eyes to the whimsical possibilities of fashion: Elsa Schiaparelli. While apprenticing with couturier Edward Molyneux, he attended Schiaparelli’s collection presentations and was immediately drawn to her innovative aesthetic. “At that moment I had never seen anything but serious clothes, and this had such charm. It set off my mind.”[4] After studying at the Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne and Académie Julian, Beene returned to New York City and set about making a name for himself on Seventh Avenue.

Day dress

Geoffrey Beene, c. 1969

Gift of Roxanne, Byrnadette & Frank DiSanto

95.817.c.1969.08.48

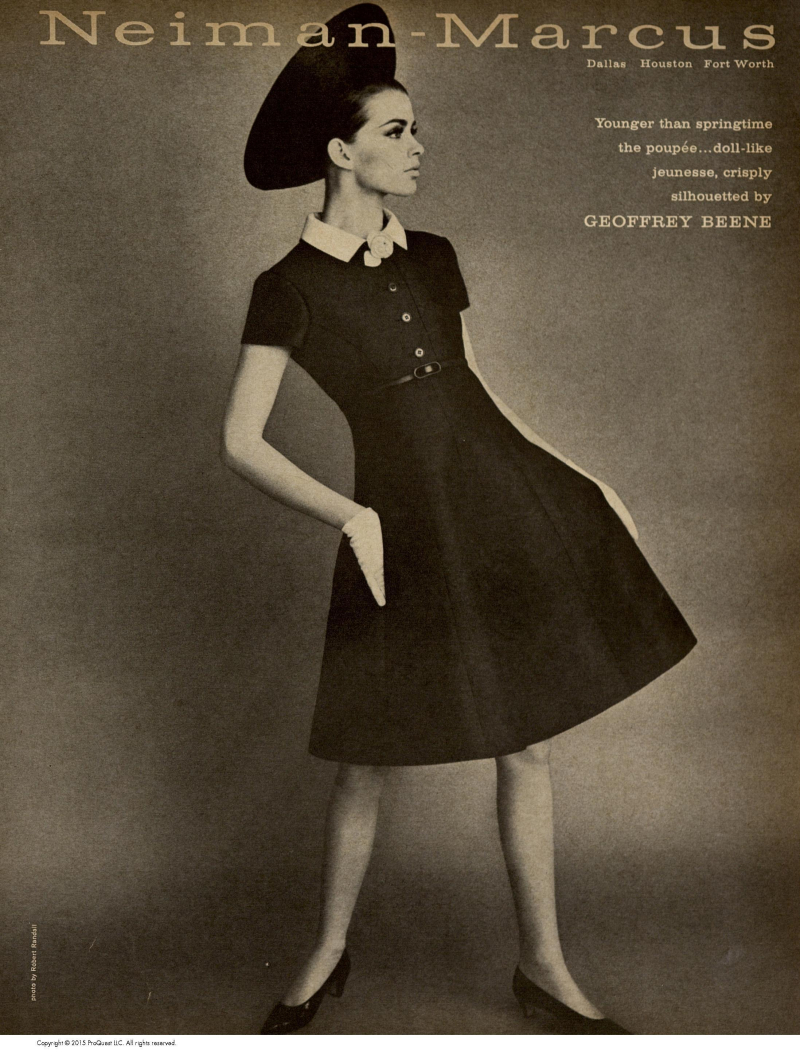

Harper’s Bazaar, February 1966

Harper’s Bazaar, February 1966

In post-war American fashion, manufacturers still reigned supreme, hiring talented young designers to produce profitable looks – for example, Claire McCardell for Townley Frocks, Rudi Gernreich for Walter Bass, and in 1952, Geoffrey Beene for Harmay. Yet while Beene was eager to experiment with new designs, Harmay only wanted interpretations of the clothes coming out of Paris. He left the brand in 1958 and found more flexibility with manufacturer Teal Traina, but it wasn’t until he opened his eponymous line in 1963 that he truly gained the artistic freedom he desired.

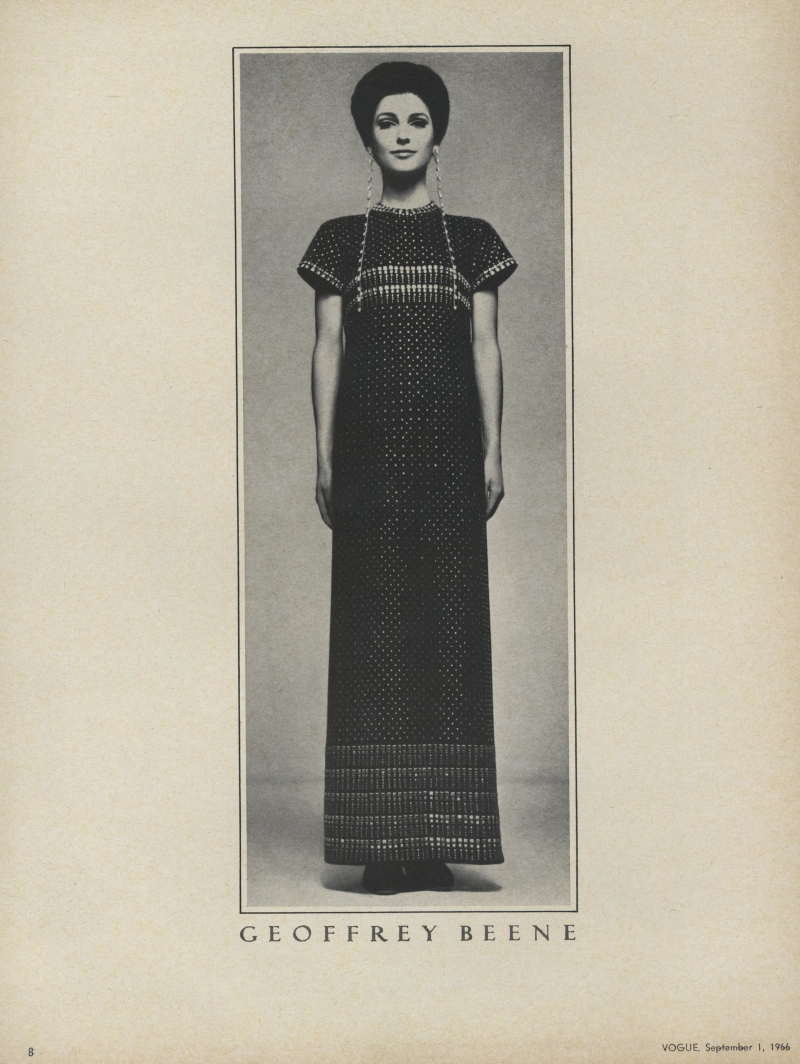

Evening gown

Evening gown

Geoffrey Beene for Robinson’s, September 1966

Gift of Judy Carroll

2014.1291.2

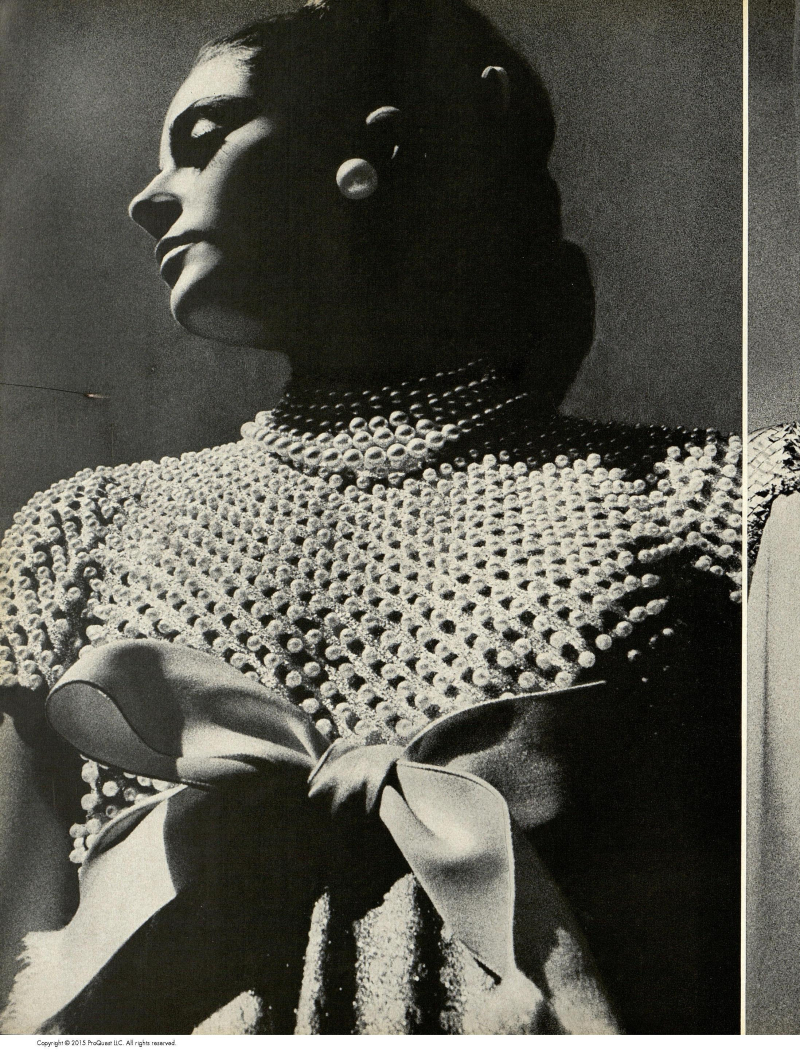

Beene’s first collection was a critical and commercial success; in 1964, he received the first of an eventual eight Coty American Fashion Critic’ Awards, the most given to any American designer.[5] He offered structured, high-waisted, short-hemmed dresses that were beautifully constructed and made with a surprising array of fabrics, from heavy silk to soft wool flannel. The wittiness he once observed on Schiaparelli’s runway made frequent appearances in his collections, such as his famous floor-length sequined football jersey gown, a dress with a bedazzled Felix the Cat, or gingham evening wear. Beene explained, “I want the clothes to be amusing – so women enjoy putting them on.”[6] His popularity earned him the commission to design Lynda Bird Johnson’s wedding gown in 1967, and he was one of the many American names that finally eclipsed the Seventh Avenue manufacturer in the 1960s: “The man behind the fashion label is no longer a faceless somebody…he is as much of a personality as an actor, with a following of social and glamorous women.”[7]

Evening gown

Evening gown

Geoffrey Beene, 1968

Transfer from The Museum at The Fashion Institute of Technology

97.c.1968.059.100

Harper’s Bazaar, November 1966

Harper’s Bazaar, November 1966

In 1973, just ten years after his label launched, Beene’s career reached a key turning point. A review in The New Yorker likened his latest collection to concrete, and asked what woman would want to wear something so unyielding.[8] Beene took the criticism to heart and went through a period of creative introspection:

“I began rethinking the question of clothes and their relation to how people lived, how comfortable they felt, how they fit into the pace of modern living. I began to conceptualize what I was doing. I spent some time in museums, looking back on the clothes people wore for five hundred years to what could be adapted for today…I decided I would aim at the younger generation, who didn’t want the stiff kind of constructed clothes other people and I had been making.”[9]

Modernity was the new guiding principle of Beene’s designs. His ability to adapt his work to the needs of real women ensured his continued success, and infused him with a renewed sense of energy and inspiration. Beene strove to make his clothing beautiful yet lightweight, effortless, and practical.[10] His medical training helped him to understand the movement and proportions of the human form, allowing him to design three-dimensionally, as an architect.[11] He began experimenting with geometric shapes – particularly triangles and circles – and curved seams to improve a garment’s fit on the body. Anything extraneous was eliminated: “The more you learn about clothes, the more you realize what has to be left off. Cut and line become increasingly important.”[12] Cropped bolero jackets and jumpsuits – ensembles that could be worn for day or night – became collection staples.

Ensemble

Geoffrey Beene, c. 1975

Gift of Mrs. Alice Avery

95.c.1975.11.02A-D

Day dress

Geoffrey Beene, c. 1975

Gift of Larry Belger & Susan Belger

2010.1130.3

In 1981, Beene was able to buy-out his partners and gain complete control of his label and aesthetic. Unlike many of his peers, he was able to design free from the burdens of commercial success thanks to the financial viability of his menswear fragrance, Grey Flannel, and the profits from licensing men’s dress shirts. In 1974, Beene had introduced a diffusion line called Beene Bag, replacing the earlier incarnations Beene Bazaar and Beene Boutique. He maintained the integrity of the line (which was open until 1984) by using almost identical designs as his ready-to-wear collection, but using less expensive fabrics to keep costs down.[13]

Ensemble

Ensemble

Geoffrey Beene, c. 1975

Gift of Mrs. Alice Avery

S95.69.1AB

Day dress

Day dress

Geoffrey Beene, c. 1970

Transfer from The Museum at The Fashion Institute of Technology

S97.291.36

Beene’s clothes are often immediately recognizable thanks to his unique choice of fabrics. Textiles were the basis of his creative process, and throughout the 1980s, he paired textures and materials together into unexpected combinations, such as quilting together linen and lightweight silk, appliquéing lace, or adding trapunto to a wool jersey evening gown (a material he called “a cure-all” [14] in fashion). Often times the interior of the garment was just as beautifully designed as the exterior, lined in a patterned taffeta only the wearer would see. Beene was also an early advocate of blurring the lines between sportswear and evening wear – in many ways, he was a fashion Nostradamus, predicting that “jumpsuits are the ballgowns of the next century”[15] (check) and that “by the turn of the 21st Century clothes will be extremely simple and functional”[16] (yes, athleisure is here to stay).

Photographs by Michel Arnaud

Photographs by Michel Arnaud

Geoffrey Beene, Spring/Summer 1995 runway presentation

Gift of Arnaud Associates, SC2000.1095.1

Beene once again proved ahead of his time when he moved away from traditional runway presentations in the 1990s. A long-time supporter of dance – he served on the board of the American Ballet Theatre – and eager to demonstrate just how flexible his garments could be, he hired dancers to perform choreography while modeling his Spring/Summer 1994 collection. The following season, for a collection inspired by Santa Monica, the dancers tossed beach balls and played with hula hoops.

Evening gown

Geoffrey Beene, 1969

Gift of Larry Belger & Susan Belger

2010.1130.5

His ground-breaking designs were praised repeatedly in the press…at least by those he allowed into his shows. Though he was a consummate Southern gentleman (he was always addressed as Mr. Beene, never Geoffrey), he was also known to be stubborn and played by his own set of rules – and that did not include pandering to journalists. He held mutual grudges with John Fairchild, the publisher of Women’s Wear Daily, and Diana Vreeland, and famously did not invite Anna Wintour to his runway presentations. The New York Times, at least, remained in his good graces and consistently recognized his originality with effusive reviews such as “He has worked out a way of dressing that suits contemporary life. It is so fluid and effortless that it makes the usual fashion descriptions worthless.”[17]

Geoffrey Beene passed away in 2004, but his legacy lives on in American design. The CFDA named their Lifetime Achievement Award after Beene, and his foundation provides millions of dollars towards fashion scholarships (among other noteworthy charity causes) annually. However, it is his singular design aesthetic – uniquely American, uniquely Mr. Beene – that continues to be completely relevant today. As one reviewer put it, “He hasn’t presented simply a collection of dresses. He has evolved a Style of dressing, which is something bigger.”[18]

[1] Bernadine Morris, “Beene, as Usual, Forges Fashion’s Path,” The New York Times, April 7, 1990. https://www.nytimes.com/1990/04/07/style/beene-as-usual-forges-fashion-s-path.html

[2] Peter McQuaid, “Clothes Made the Man,” The New York Times, October 20, 2002. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/10/20/magazine/style-clothes-made-the-man.html

[3] James Wolcott, Beene by Beene Geoffrey Beene (New York: Vendome Press, 2005), 21.

[4] Nina Hyde, “Geoffrey Beene, Simply Elegant” The Washington Post, April 19, 1987, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1987/04/19/geoffrey-beene-simply-elegant/117ca3b3-24eb-4979-9ee3-a85993bf5a15/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.37346ecf30b8

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Beene’s New Direction,” Women’s Wear Daily, January 5, 1973.

[7] Patricia Peterson, “The Names Behind the Labels,” The New York Times, June 27, 1965, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1965/06/27/97214435.html

[8] Anne-Marie Schiro, “Geoffrey Beene, Innovator of American Fashion, Dies at 77,” The New York Times, September 29, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/29/obituaries/geoffrey-beene-innovator-of-american-fashion-dies-at-77.html

[9] Barbara Walz and Bernadine Morris, The Fashion Makers (New York: Random House, 1978).

[10] Anne-Marie Schiro, “The Incredible Lightness of Beene,” The New York Times, November 1, 1994, https://nyti.ms/298FhbS

[11] Nina Hyde, “Geoffrey Beene, Simply Elegant” The Washington Post, April 19, 1987, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1987/04/19/geoffrey-beene-simply-elegant/117ca3b3-24eb-4979-9ee3-a85993bf5a15/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.37346ecf30b8

[12] Daphne Merkin, “Where You Beene?,” Elle, February 18, 2011, https://www.elle.com/fashion/a11544/geoffrey-beene-american-designer/

[13] Wolcott, Beene by Beene Geoffrey Beene,34.

[14] Bernadine Morris, “Fashion with Style: 30 Years of Geoffrey Beene”, The New York Times, February 18, 1994, https://nyti.ms/2983WJU

[15] Geoffrey Beene and Grace Mirabella, Geoffrey Beene: Unbound (New York: Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, 1994).

[16] “Pro Talk: Geoffrey Beene,” Women’s Wear Daily, April 23, 1969.

[17] Bernadine Morris, “Beene: Becoming a Milestone in American Fashion,” The New York Times, November 9, 1977, https://www.nytimes.com/1977/11/09/archives/beene-becoming-a-milestone-in-american-fashion.html

[18] Bernadine Morris, “Beene: Becoming a Milestone in American Fashion,” The New York Times, November 9, 1977, https://www.nytimes.com/1977/11/09/archives/beene-becoming-a-milestone-in-american-fashion.html