At the end of 2020, the fashion industry lost an icon: Pierre Cardin, a cultural revolutionary whose career spanned over seven decades. Best known for his futuristic designs that embodied the youthful ideals of the Space Age and swinging sixties, Cardin contributed more than just his forward-thinking aesthetic to the fashion world. In a time when many designers looked down on ready-to-wear, licensing, and diffusion lines, Cardin saw only opportunity. His cunning business acumen kept him active and relevant in an ever-changing industry.

Wool gabardine suit

Pierre Cardin, c. 1968

Gift of Laura Jarre

87.1968.012.17AB

Pierre Cardin was born “Pietro” in a small town outside Venice, Italy in 1922. His parents, looking to escape Italy’s growing fascist regime, immigrated the family (Cardin was the youngest of 11 children) to Saint Étienne, France in 1924. He studied architecture before apprenticing with a tailor in Vichy; his understanding of architectural concepts is clear in his structural designs, such as the 1969 “egg carton dress” made from Cardine, a signature synthetic heat-molded textile. He placed the silhouette of the garment above flattering a figure, explaining that clothing was meant “to give the body its shape, the way a glass gives shape to the water poured into it.”[1]

Wool garbardine suit

Pierre Cardin, c. 1968

Gift of Laura Jarre

87.1968.012.16AB

Suit detail

After volunteering with the Red Cross during World War II, Cardin followed his passion for design to Paris, where he worked under Jeanne Paquin, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Jean Cocteau, assisting the latter in costume designs for the 1946 film La Belle et la Bête. He was hired at the nascent House of Dior in 1946, and witnessed the debut of the hourglass Bar Suit, which became a worldwide sensation. Cardin was assigned to coats and suits, honing couture tailoring skills that he would utilize in later years for both his men’s and women’s collections.

Wool twill jumper

Pierre Cardin, 1966 – 1968

Gift of Anonymous Donor

2003.40.6AB

Detail of jumper neckline; bow sits at the back of the neck.

Throughout his career, Cardin was singularly focused on business. In 1950, at the age of 28, he purchased a costume shop in the attic of a building on Rue Richepanse and officially launched his eponymous brand. Over the years, as his revenue increased, he bought floor after floor until he owned the entire building. His aesthetic in the 1950s marked a time of transition from the couture world to his avant-garde looks. The wildly popular 1954 “bubble dress” was followed by coats with dramatic oversized collars. A 1957 trip to Japan introduced him to model and muse Hiroko Matsumoto; the next year, he became a professor emeritus at Bunka Fashion College (attended by Kenzo Takada in 1958). By the end of the decade, he launched “Cylindre,” his first menswear collection that included sleek, collarless suits for men – a style later popularized by The Beatles.

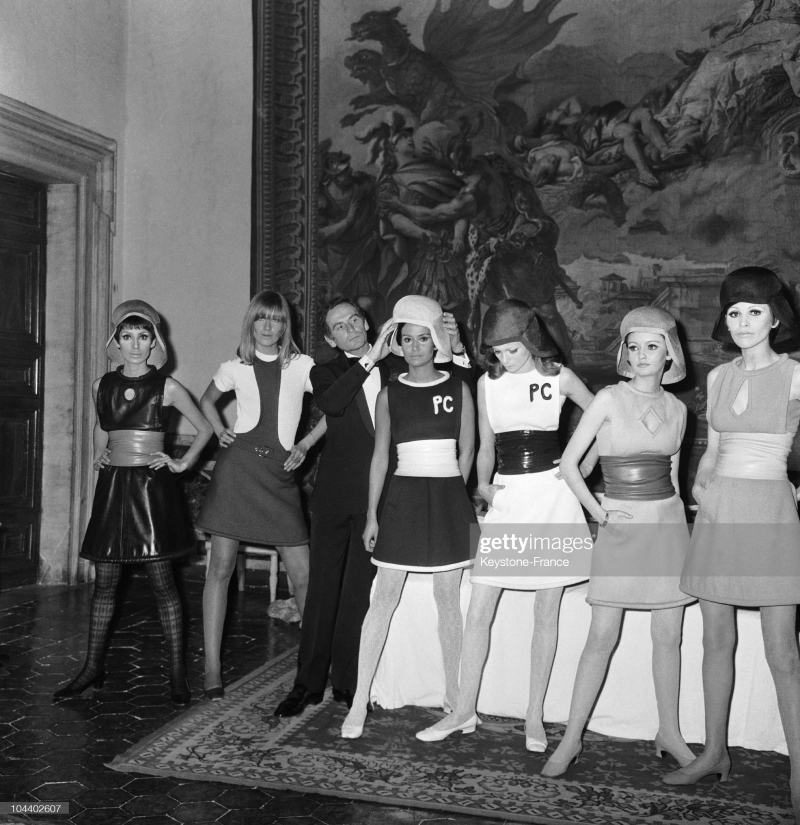

A jumper similar to the example in the FIDM Museum (second from left) is styled with a white tee-shirt. Fashion show at the Farnese Palace, the French Embassy in Rome, May 10, 1967. Photo: Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images.

The year 1959 was a turning point for Cardin: he made history by showing a ready-to-wear collection at the Printemps department store in Paris. The move caused his temporary expulsion from the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture Parisienne, the governing board of French couture designers. Cardin was later reinstated, but left again on his own accord in 1966. The show indicated Cardin’s desire to leave the rarified air of couture, and instead focus on of-the-moment designs worn by the fashion-forward youth of London, Paris, New York, and Tokyo – still constructed with the fine craftsmanship and precise tailoring he was known for. Inspired by the Space Age, Cardin incorporated new materials such as foil, vinyl, plastics, and synthetics into his clothing. Silhouettes became increasingly daring and concepts more surreal, as seen in his 1966 “cosmocorps” collection: Cardin’s imagining of what men, women, and children might wear on the moon. Models sported mod minis, jumpers worn with contrasting leggings and bodysuits, jumpsuits, and matching helmets. The FIDM Museum holds a purple wool narrow-cut jumper from this collection, which was styled with black turtlenecks or plain white tee-shirts underneath. A bow on the neckline adds a feminine touch to the simple cut.

Wool crêpe dress

Pierre Cardin, 1969

Gift of Anonymous Donor

80.1960.058.19

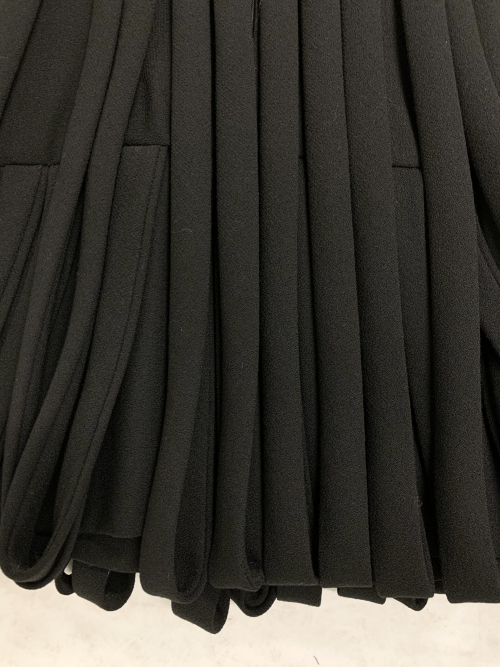

Detail of loops draping from the high bodice and attached several inches above the hem.

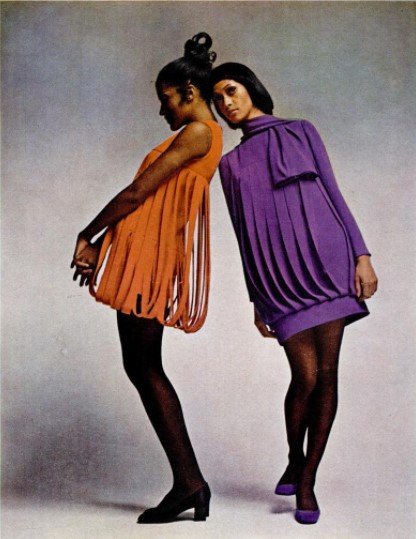

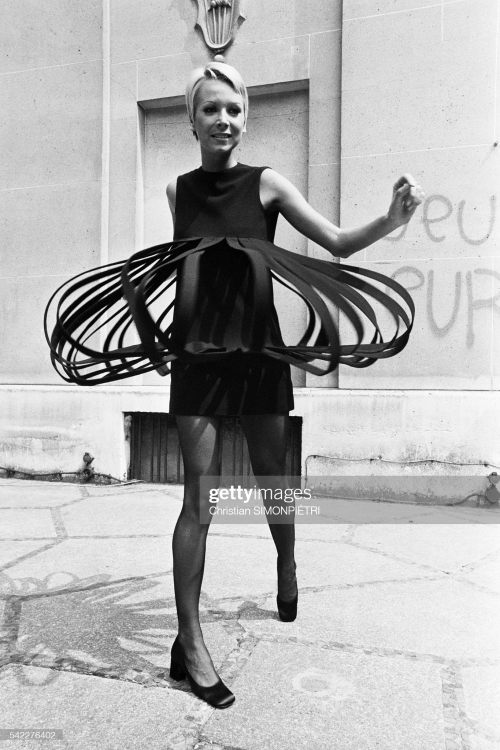

In addition to his admiration of new technologies, Cardin also took inspiration from culture and the arts. He was particularly fascinated with the Op Art movement, which uses geometric shapes and stark color contrasts to create optical illusions. Cardin experimented with the concept of negative space and geometric shapes throughout the 1960s. He began creating wool crêpe dresses and skirts with parallel strips of fabrics that swayed freely over the body. He later looped the strips of fabric to hang over a simple shift dress; dubbed the “carwash” dress because the loops resembled the oversized brushes of a drive-through car wash, the unexpected movement of the garment captures the momentum and experimental feeling of the swinging sixties.

Orange “car wash” dress (left) featured in Ebony Magazine, November 1969, page 142.

“Car wash” dress photographed in motion, July 1, 1969. Photo: Christian SIMONPIETRI/Sygma via Getty Images.

Cardin once stated, “I was born an artiste, but I am a businessman,”[2] and his strategic commercial dealings proved this to be true. In 1970, he purchased the Théâtre des Ambassadeurs, an old nightclub in Paris, and reopened it as L’Espace Cardin: an all-purpose event space for fashion shows, art exhibitions, plays, and cinema. He launched his first men’s fragrance, Pour Monsieur, in 1972 with an overtly masculine phallic-shaped bottle. As evidenced through his early studies, architecture and interior design were important to Cardin. He owned several noteworthy properties around the world, and became a cultural sponsor of sorts to the communities he resided in. In 1981, he bought and renovated the famous Maxim’s restaurant in Paris, and later expanded it as an international franchise.

Pierre Cardin Fragrance, c. 1992

Gift of Annette Green Museum at the Fragrance Foundation

F2005.860.457AB

Yet Cardin’s crowning business achievement was his proliferation of licensing contracts. He was a true pioneer of licensing and normalized the practice within the fashion industry. Clothing, accessories, furniture, household goods, automobiles, food, fragrances – no consumer field was off-limits. The New York Times estimates he once held upwards of 800 licenses in 140 countries. Loaning his initials to a product – be it a clock, chocolate bar, or set of sheets – allowed those who could not afford his fashions to own a small piece of the glamour the Pierre Cardin label represented. It ensured financial stability for his brand; Cardin maintained sole ownership in his lifetime, taking on no other investors. Cardin demonstrated an extraordinary work ethic from the day he began designing: “I don’t play cards, I don’t smoke, I don’t drink, I don’t like sports. I just work. It’s marvelous. It amuses me.”[3]

Knit cocktail dress with sequins

Pierre Cardin, c. 1968

Gift of Anonymous Donor

2018.40.609

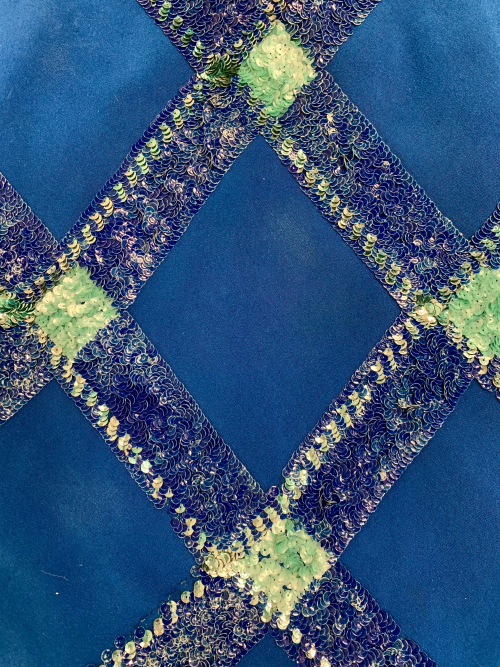

Detail of sequin pattern

Cardin began to show smaller collections and focused on reissuing his most popular Space Age styles in the 1980s and 90s. Always one to push boundaries, he was among the first high-end designers to do business with communist China, and daringly presented his 1991 collection in Moscow’s Red Square. In 2014, Cardin opened the Past-Present-Future Museum in Paris as a permanent showcase of his impressive body of work; stateside, the Brooklyn Museum held a retrospective called Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion in 2019. Cardin was named a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador in 1991, where he was celebrated for his philanthropic efforts in using the arts to promote tolerance, and received the Légion d’honneur award from the French government the same year.

A true visionary who never stopped creating, Pierre Cardin left an indelible mark on the fashion world – not only in the inventive nature of his designs but in the very fabric of how the industry does business. Always imagining the look of the future, Cardin perfectly summarized his design ethos: “The dresses I prefer are those I invent for a life that does not yet exist.”[4]

Pierre Cardin on his 1990 couture runway; photo by Michel Arnaud. FIDM Museum Special Collections.

[1] Ruth La Ferla, “Pierre Cardin, Designer to the Famous and Merchant to the Masses, Dies at 98,” The New York Times, December 29, 2020.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Morwenna Ferrier, “French Designer Pierre Cardin Dies Aged 98,” The Guardian, December 29, 2020.