For our latest blog post, the FIDM Museum’s Associate Curator Christina Johnson does a deep dive into the most American of fabrics: denim. The impetus for her research is a rare coat in our permanent collection, and her path to interpreting it winds through the complex history of cotton and enslaved labor in the United States.

When FIDM Museum Curator Kevin Jones texted me a photo of a circa 1855 man’s frock coat, I knew it might be something special because it looked like it was made from denim.1 Today, just about everyone I know has denim in the closet (possibly even a surplus of it!). We have denim jackets—maybe stone washed, maybe acid washed, maybe even covered with trendy enamel pins; then there are “jeans”— stretch, Mom-style, baggy, skinny leg, bell-bottom—and don’t forget shorts and cut-offs. Some people might have learned a denim timeline that begins when the cloth was utilized for miners’ pants during the California Gold Rush, before transitioning to tough-looking streetwear in the 1950s, and ending with its adaption as designer must-haves of the 1990s. But this now ubiquitous American clothing fabric has an earlier, broader, and more complicated history than that. Investigating the early years of denim in the United States is challenging, in part, because finding clothing made from the material dating to before about 1900 is rare.2

First, let’s define denim: it’s a heavy grade, warp-faced twill-woven cotton fabric; the twill weave structure is characterized by tight diagonal ridges. An indigo blue-dyed cotton warp and white cotton weft create denim’s famous washed or mottled look. I know of only a few pieces of pre-1900 denim garments in museum collections. The Museum at FIT has a pair of circa 1840 men’s brushed cotton pants later dyed blue and appliqued with denim patches; they also hold a woman’s bodice from about 1860 (possibly chambray). The Levi Strauss & Co. Archive has the earliest pair of their 501-style denim “jeans,” (trousers, or waist overalls) from the late 1870s. Historically, denim was also used on the interior of garments when durability was required; for example, an early nineteenth century linen and wool vest in the collection of the Indiana State Museum incorporates denim patches on the back of the pockets. The FIDM Museum owns a woman’s bathing cover-up from about 1865-70 and a pair of 1850s men’s unworn trousers, both of brown sulfur-dyed denim. Other pieces have come up at auction.3 Where or by whom an object is worn adds much to analysis. Unfortunately, the dealer we acquired the FIDM Museum denim coat from would only tell us they purchased it “in the Midwest.” It’s disappointing to not have a town of origin to work with, or the name of an associated family. Every bit of information adds to the analysis of an extraordinary piece like this.

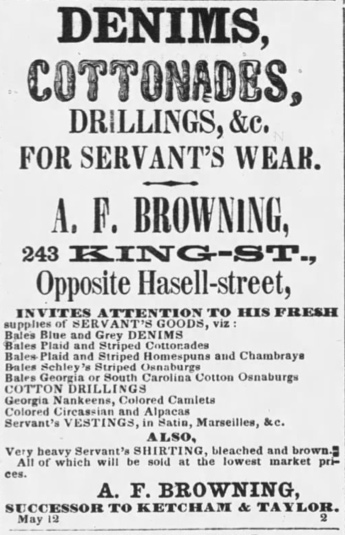

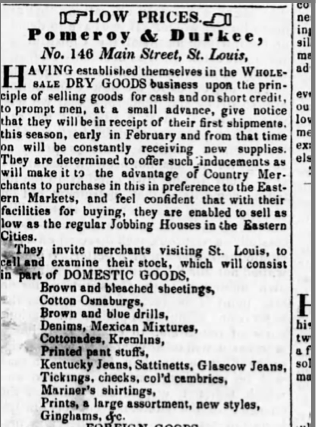

The English word “denim” is likely a corruption of the French phrase serge de Nîmes, translated as serge [silk/wool twill fabric] from Nîmes, a town in Southern France. This name would suggest the cloth was produced in Nîmes, and then exported. However, some scholars believe the name was also applied to early British-manufactured denim, because French verbiage lent cachet to consumer goods.4 In the English-speaking world, “Serge denim” (the anglicized form of serge de Nîmes) was offered for sale in British newspapers in the early eighteen century.5 Denim imported from Britain was advertised in colonial North American newspapers by the late eighteenth century.6 It’s not clear when denim transitioned from being a silk/wool blend to 100% cotton, but it’s likely related to the proliferation of cotton crops in the United States, produced and processed by enslaved laborers of African descent. One of the earlier mentions of denim being woven in the United States is from a 1789 Poughkeepsie, New York, newspaper. It describes a factory in Boston turning out “cotton dyed and printed, fustians, jeans, denims, [and] cottonades….” Although today the words “jean/s” and “denim” are used interchangeably, they signified different heavy-weight goods during the mid-nineteenth century: in part, “jean” was a twill fabric featuring a warp and weft of the same color, whereas “denim” had warp and weft colors that differed.7 American newspaper advertisements often promoted domestically produced textiles, as seen in the above 1846 ad from a Missouri shop. By the time the FIDM Museum coat was made, denim fabric was mass-manufactured in the U.S., and didn’t need to be imported into the country.8 Although it’s not known for certain (no real provenance, remember?), it’s likely this coat was constructed from an American textile.9

Before the first few decades of the nineteenth century, people’s clothes were made from hand-woven material and were entirely hand sewn. Technological developments changed this. The FIDM Museum denim coat exhibits both machine- and hand sewing. Its major seams, such as the diagonal seam attaching the cream-colored cotton lining to the denim, were done with a sewing machine. Sections that needed reinforcement for durability, such as the interior pocket, were also machine-stitched. Other areas, like the buttonholes and the jacket skirt lining, were finished by hand. American newspaper advertisements testify that new, mechanized sewing machines were in use at many tailoring establishments by about 1850; in fact, proclaiming one’s business had this technology was a novel selling point to customers! The sewing machine—described in one period source as “perfection,” “a most ingenious piece of mechanism,” and “able to perform 200 stitches to the minute”10 —was a marvel to people who had been used to only having a needle, spool of thread, and their hands for sewing.

The U.S. ready-to-wear clothing industry expanded each decade of the nineteenth century; menswear comprised a high percentage of the output, perhaps because a looser fit was generally more acceptable in male attire at this time.11 Previously, new clothing was custom-fit to individual bodies. Whether hand-sewn or machine-produced, ready-to-wear meant exactly that—a person tried-on and purchased an already finished or partially finished garment, saving time (no need to obtain fabric from a merchant, discuss styles with a tailor, or engage in numerous fittings with a seamstress) and thus, cost. However, sartorial individuality could be lost the more pre-made elements a person purchased. It’s unknown if this coat was produced ready-to-wear or tailored (with both hand and machine sewing) for an individual body. It’s a slender size, with an approximately 36” chest and 31” waist.

Carol M. Highsmith

Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress

Fertile soil and warm weather conditions in the Southern states are favorable to propagating cotton. But planting, picking, and processing the harvest was labor intensive—even with mechanical innovations like the cotton gin (invented by Eli Whitney in 1793) to speed the process. After usurping land from Indigenous Peoples, many American farmers exploited people of African descent to work their cotton crops. American enslavers made fortunes from “white gold,”12as some scholars have called cotton, and quickly took over the European market. By 1857, almost seventy percent of all cotton arriving into the United Kingdom to be woven into cloth was grown in the United States.13 American cotton’s low cost was made possible from the unpaid labor. At the time the FIDM Museum cotton jacket was constructed, more than 3.2 million Black people were enslaved in the U.S.14 As noted in this 1853 excerpt from American Cotton Planter magazine, enslavers published explanations to bolster psychological support for the monetary prosperity slave-produced cotton extended:

Slave-labor of the United States, has hitherto conferred, and is still conferring inappreciable blessings on mankind. If these blessings continue, slave-labor must also continue, for it is idle to talk of producing cotton for the world’s supply with free labor. It has never yet been successfully grown by voluntary labor.”15

Much of the raw cotton produced in the U.S. was exported into the U.K. to be woven and then imported back as whole cloth. However, copious yardage was also manufactured in the U.S.. In fact, by 1810, the federal census noted 269 cotton factories in the country.16 European immigrants also worked in the burgeoning American textile industry. One turn-of-the-nineteenth-century commentator stated:

There have arrived in the United States from Europe, a very considerable number of engine and machine makers, carders, spinners, rovers, twisters, weavers, calico printers, dyers etc., ready to work on wages as moderate as they received in Great Britain, Ireland, and other parts of Europe.”17

A substantial portion of the American population worked (unpaid and paid) in the cotton and clothing industries; many hours and many hands went into producing this denim coat.

Indigo is a plant-derived dye with a centuries-long history of cultivation around the world. Like cotton, it became a Southern cash crop during the early nineteenth century. The knowledge of indigo cultivation and dye production likely originated in West Africa. Extracting the blue pigment from the green leaves was labor intensive, and involved soaking the crushed plant in water and utilizing harsh chemicals such as lye. Small cakes of the blue pigment were formed by hand, which was absorbed into the fabric after multiple soakings and dryings.18 Oxidation (exposure to air) is responsible for producing indigo’s signature color. This blue hue was aligned with denim by the first part of the nineteenth century and many advertisements didn’t list “denim” without the modifier “indigo” first.19No other textiles sold at this time were as visually or linguistically connected with the color blue as denim was.

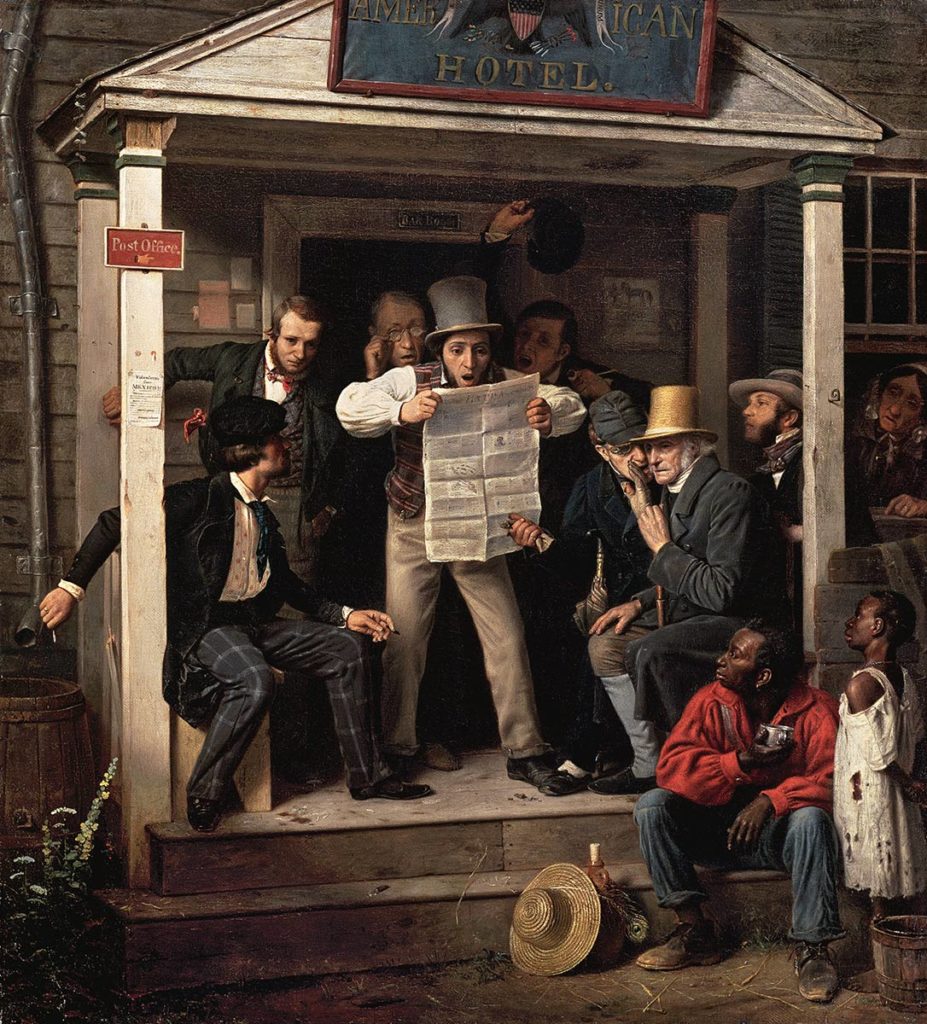

George Caleb Bingham

Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Ezra H. Linley by exchange, 50:1934

Advertising and visual imagery produced at the time the FIDM Museum coat was made suggest denim was aligned with work wear— after all, manual labor necessitated durable materials. For example, Nashville shopkeeper John Beaty offered an extensive stock of dry goods and clothing in 1849, and specifically included the descriptor: “work denim.”20 Denim was made famous by Levi Strauss, a San Francisco dry goods merchant known for his wide selection of work fabrics and clothing marketed to miners during the California Gold Rush of 1849. Later, he joined with business partner J.W. Davis to utilize a patented metal-rivet system for denim pants to increase the durability at stress points.21 Moving from landlocked shores to the seas, it’s interesting to note that mid-nineteenth century sailors also wore denim. The Seamen’s Aid Society Clothing Store was located in Boston; it sold gear intended to “fit out seamen, or other gentlemen going to sea, complete for a voyage.”22 Ready-made clothing offerings included denim “trowsers [sic] and denim frocks” (the latter referred to frock coats, not dresses).23Additionally, perusing mid-century waterscape paintings reveal tantalizing hints of denim wardrobes. For example, as shown above, Missouri-based George Caleb Bingham depicted a group of working-class men taking a break as they float along a river on a warm day, wearing sun-shielding hats, loose cotton or linen shirts, pants of varying materials, and heavy leather shoes. The card player in the red shirt wears a pair of light blue pants with hems turned up to reveal the cloth’s lighter underside.24 It’s possible he’s wearing denim.

People living in American penitentiaries and almshouses were often given uniform-like clothing to wear during this era. The handouts were generally made of inexpensive, durable materials that set wearers apart from people outside of institutionalized life. In Manhattan, people who committed crimes, were un-housed, or suffered from mental illness were often confined to Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island), situated in the East River between Manhattan and Queens. Located on the island were hospitals, an almshouse, orphanage, workhouse, and penitentiary. In 1851, the store house (supply warehouse) listed the fabric and clothing available for the confined residents, including: 1,090 yards of burlap, 505 1/2 yards of calico, 869 1/2 yards of prison cloth, and 12,899 ¼ yards of denim, among other fabrics.25 Also on hand were 400 denim frocks, thirty-three denim shirts and eighteen denim jackets; these items were made by workhouse inmates to clothe the island population.26

British advertisements provide evidence that servants have worn denim since at least the eighteenth century. In 1717, an ad describing a missing (likely indentured) servant appeared in The Post Boy, a London newspaper:

Whereas Thomas Gaile, about 20 years of age…light colour’d old cloth coat and wastcoat, with a striped Holland wastcoat [sic], a blue shirt and blue serge denim breeches, has been missing from his mistress Katharine White rope-maker.27

Denim was a serviceable choice of cloth appropriate for the physically demanding work of twisting and braiding yards of heavy jute into rope. In the U.S., the alignment of denim with servitude certainly increased in the two decades before the American Civil War, as shown again and again in newspapers advertising denim “for servant’s wear.”28 In 1854, one southern mercer hawked “blue denims for servants.”29 “Servants” was often coded language referencing enslaved Black people. Enslavers purchased or made cheap clothing out of serviceable fabrics to cut down on operating costs because hours of manual labor quickly wore out finer fabrics.30 Judging from advertisement references, denim was a popular choice, along with drill, jean, and osnaburg (a durable plain-woven linen/cotton blend also used for food storage sacks).31 Writing about the many types of cotton fabric used for clothing the enslaved, an 1853 source stipulated:

The peculiar qualities of its fibre [sic], uniting length, strength, firmness, softness and cheapness, its spiral form, its chemical properties as a non-conductor of heat and electricity, and its absorbent properties, all unite to make it the healthiest, cheapest, the most comfortable and convertible of existing materials for human clothing….”32

Merchants’ ads often divided fabric and clothing offerings as to type of intended wearer. In 1835, South Carolina merchants McDowall & Co. listed specific fabrics for “Gentlemen’s wear,” “children’s wear,” and “servants’ wear.” The listing for gentlemen included French bombasins, doe skin, ermine, fancy diagonal drill, and double merino. Available for children was Peruvian fancy drill, cassimeres, India Nankeen, and striped jeans. Servant clothing was regulated to: Hamilton jeans, unbleached linen drill, drab fustians, and blue denims.33 It’s obvious that the last wearer category only included inexpensive, durable, and plain fabrics, whereas the former two categories had fancier and more delicate yardage, including costly imported goods.

A group huddles around a newspaper being read aloud in the 1848 painting War News From Mexico. The men wear everyday dress—a mix of tailored and ready-to-wear separates made from contrasting materials. Relegated to the bottom portion of the painting sits a man segregated from the group on the porch, clothed in what appears to be patched denim pants rolled up at the ankles, along with a bright red shirt, worn-out leather shoes, and a straw hat trimmed with a peacock feather. This genre painting doesn’t depict an exact moment or location, but instead, was meant to serve as an analogy for American society (note the generic “American Hotel” sign with no further information to situate the scene as to a particular town). Then as now, wardrobes made social standing instantly visible; the man’s heavily mended denim pants and worn shoes (as well as the nearby child’s ragged shift and lack of footwear) reveals individuals of lower social and economic status than those who wear higher-quality dress.34 This painting specifically aligns (poor condition) denim clothing with a lack of monetary prosperity and outsider status from hegemonic society.

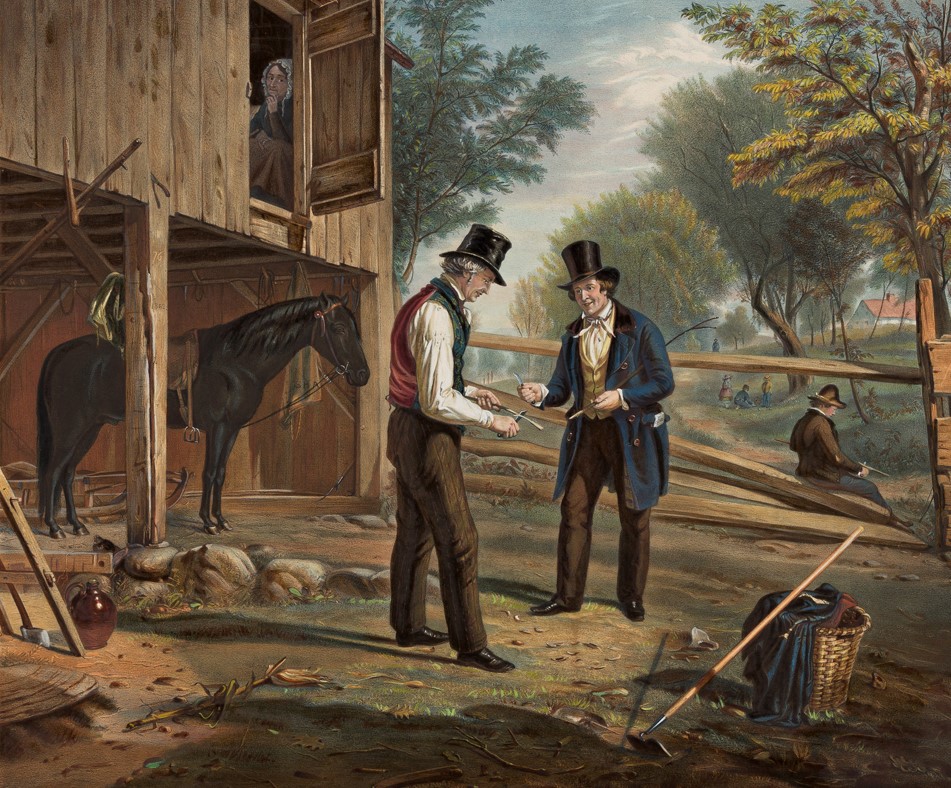

In the lithograph Coming to the Point, two men engage in conversation as they whittle wood; the title functions as wordplay to suggest not only the sharpening of twigs, but coming to a clear and direct understanding about the price of the horse just behind them. The men inhabit a rural genre scene, and stand by a rough-hewn barn surrounded by tools of manual labor—including a hoe, basket, ax, and plow. One of the men doesn’t wear a coat, suggesting this meeting is an informal occasion. The other man does have a coat on, that—with its dark blue color, details of pattern and cut, button placement, and pastel striped lining—is remarkably similar to the FIDM Museum’s example. Mid-nineteenth century lithographs democratized art for the burgeoning middle class. These mass-produced paper images were often framed, making them affordable options for decorating home interiors. Some of the most popular lithographs took on wholesome genre paintings as their subject matter. Here, admirable “American” qualities of hard work (signified by the farm implements), informal attitude and lack of pretention (suggested by the coatless farmer man and the denim-coated visitor), as well as the inherent beauty of the rural U.S. landscape (shown by people in the distance sitting in the lush countryside) permeate this illustration.

American working-class culture often bemoaned male (and particularly female) adherence to the costly European fashion system—mainly derived from Paris, France—that often necessitated over-expenditure to keep up. A misogynistic and racist quip directed to the “working-man” published in The American Mechanic and Working-Man sums up this way of thinking:

Every one [sic] is ready enough to cry out against the tyranny of fashion, yet almost every one meekly submits….I am no friend to mere fashion as a directress of life; she is a capricious sultana who mocks us into disguises, and then punishes us for compliance. Who can tell the money out of which she has cheated the mechanics of America!35

Because hardwearing denim was an inexpensive fabric—much cheaper than the typical woolen yardage that went into most coats— it didn’t compete with the fads for patterned silk brocades and velvets, instead, it remained a serviceable, monochrome (blue or brown) choice season after season.

As frustrating as it is when provenance is lost, an opportunity arises because an object transforms from a statement into a dialogue. Analyzing this coat and contextualizing it within a framework of many different written and visual sources has elucidated the complexity of American-worn denim in the mid-nineteenth century. Because it’s linked to cotton production, denim can never be extricated from slavery. But was this coat worn by an enslaved male? The provenance of a Midwestern origin makes it possible: Missouri was home to more than 87,000 enslaved people in 1850.36 But denim was also worn by a variety of people, including those experiencing institutionalized life. Additionally, denim was appropriate as everyday attire, and an alternative to partaking in an expensive foreign fashion system. Denim clothing was a manifestation of the mechanical innovations in the U.S., such as the successful textile industry and introduction of the sewing machine. Why was this coat saved for more than 150 years? It has a fashionable, elongated cut, but is worn, stained, and at one point, the buttons were even removed—probably for re-use. Did the original owner associate it with a memory or emotion they wanted to preserve? Was it re-worn by more than one member of a family or generation? Or, was it simply forgotten in an old trunk or attic? This blog entry is just the beginning of analysis into the FIDM Museum’s early denim coat. As always, we invite you to share your thoughts and ideas with us. Please join in the conversation.

Hyperlinks:

- circa 1840 men’s dyed brushed cotton pants – https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/denim-fashion-s-frontier-circa-1840-pants/agHhRGDashQcSg?hl=en

- woman’s bodice from about 1860 – http://fashionmuseum.fitnyc.edu/view/objects/asitem/search$0040/64/dynasty-desc?t:state:flow=0e2aa414-f2ab-45be-b817-13b6d3df2e60

- vest in the collection of the Indiana State Museum – https://collection.indianamuseum.org/mwebcgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=37881;type=101

- bathing cover-up from about 1865-70 – https://fidmmuseum.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/4E647D83-5943-422D-9CD3-033209318700

- Note the original buttons are missing; their circular shape is still delineated on the textile. They were likely made of gutta-percha, wood, or metal. Reproductions will be made in the future.

- Thank you to: Clarissa Esguerra, Associate Curator, LACMA, Costume & Textiles; Shelly Foote, Assistant Chair Emeritus, Smithsonian Institution, Division of Social History; and Peter Liebhold, Curator Emeritus, Smithsonian Institution, Division of Work and Industry, for their thoughtful conversations regarding this object.

- See First Empire era denim coat at Drouot auction: Textiles à Lyon #10, Oct. 7, 2021, Lot 210

- Lynn Downey, “A Short History of Denim,” 2014, levistrauss.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/A-Short-History-of-Denim2.pdf

- The Maryland Gazette (Annapolis, Maryland), August 28, 1751, 3.

- For example, in the summer of 1772, goods imported from England offered by Isaac Hazelhurst of Phladelphia, Pennsylvania, included: earthenware, Irish linen, writing paper, linen and cotton, and denim for breeches. See: The Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) June 15, 1772, 6.

- Downey, Op. cit.

- For example, in 1849, The Amoskeag Manuf. Co., in Manchester, New Hampshire, produced 13.5 million yards of “shirtings, cotton flannels and denims per year.” The Franklin Manuf. Co. in Massachusetts manufactured 380,000 yards of denim cloth per year. See: New-England Mercantile Union Business Directory, New-York: Pratt & Co, 1849.

- Sometimes the visual details of the selvage (the fabric’s woven edges on the interior of garments) can identify a region or the factory of manufacture; in the future, consulting someone knowledgeable about selvage identification will hopefully yield additional understanding about this object.

- “Important to Tailors,” The Perry County Democrat (Bloomfield, Pennsylvania), November 13, 1845, 1.

- For example, Wisconsin-based James M. Otis advertised “a very large and splendid assortment of Fall and Winter Goods” from New York City; this included “ready-made-clothing” such as “frock and over coats, pants, vests….” See: Grant Country Herald (Lancaster, Wisconsin), December 30, 1843, 3. This offer of ready-mades in the United States was nothing new: As early as 1811, W. and J. Weyman and Co. of Charleston, South Carolina, advertised “Ready Made Clothing, made up in the most complete manner, and of the best quality of Goods [sic]; which they will sell at such low prices….” Listed was a lengthy assortment of menswear, plus selections for women: “Travelling Great Coats and Cloaks, Walking Frocks and [illegible], Dress Coats and Riding Coatees, Pantaloons and small clothes, Waistcoats and under Vests, Draws, Shirts, and Dressing Gowns, Childrens elegant trimmed Hussar Suites, Youths, Servants, and Sea Clothing, of every description, Ladies Travelling COATS and silk PELISSES of the latest fashions.” See: The Charleston Daily Courier (Charleston, South Carolina) April 6, 1811, 1.

- Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Vintage Books, 2014, 88.

- Previously, it had been grown by smaller production farmers in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Beckert, Op. cit., 84.

- Statistics of the United States, Chapter 5 [partial citation available online, c. 1850], 82. www2.census.gov.

- “‘A Memoir,’ extracted from a book by Isaac Croom, Greene County,”American Cotton Planter,January 1853, 11.

- Beckert, Op. Cit.

- Tench Coxe, “On the Cultivation and Manufacture of Cotton in America,” 1802, reprinted in: Niles’ National Register, (St. Louis, Missouri), June 27, 1835, 284.

- For a world history of indigo production and usage, see: Catherine LeGrand, Indigo: The Color That Changed The World, London: Thames & Hudson, 2013.

- For example, “Indigo Blue denims” in Fogartie & Deland ad, The Charleston Daily Courier, (Charleston, South Carolina) July 11, 1855, 3; “Indigo Blue denims” in Haggarty, Draper & Jones ad, The Evening Post (New York, New York), May 1, 1851, 2; and “blue denim” in French & Jerauld ad, The Evansville Daily Journal (Evansville, Indiana), May 28, 1857, 4.

- John Beaty ad, Daily Nashville Union (Nashville, Tennessee) February 17, 1849, 3.

- https://www.levistrauss.com/levis-history; see also U.S. Patent No. 139, 121, “J.W. Davis, Fastening Pocket Openings,” May 20, 1873.

- Twentieth Annual Report of the Boston Port Society For the Year 1848-49, Boston: Eastburn’s Press, 1849.

- Ibid.

- Upon close inspection, there are white stripes on the surface of the painted pants. I’m unsure if this is a technique to capture the mottled appearance of denim, or, if it’s another type of material (possible jean) with a woven pinstripe.

- Third Annual Report of the Governors of the Alms House of New York for the Year 1851. Wm. C. Bryant & Co., Printers, 16 Nassau Street, 1852, 148.

- Ibid. 133, 136, 150.

- The Post Boy,(London, England) January 30, 1717, 2.

- A.F. Browning ad, The Charleston Daily Courier (Charleston, South Carolina) May 13, 1857, 3.

- Fogartie and Deland ad, The Charleston Daily Courier (Charleston, South Carolina) June 28, 1854, 3. Note: there are huge numbers of ads aligning denim with “servant” clothing in mid-nineteenth century newspapers.

- American illustrations of enslaved Black people are rare, but some give tantalizing suggestions of denim attire. For example, some of the coats and breeches worn by men in Music and Dance in Beaufort County, a c. 1785 watercolor in the collection the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, 1935.301.3AB.

- Katie Knowles, Fashioning Slavery: Slaves and Clothing in the U.S. South, 1830-1865. Rice University, 2014, 47-48.

- “A Memoir,” Op cit, 10.

- McDowall & Co ad, The Charleston Daily Courier (Charleston, South Carolina) April 25, 1835, 3.

- For an overview about denim’s inextricable link with African American history, including the contributions of enslaved people within the American denim industry, see https://thenewfashioninitiative.org/the-untold-history-slavery-blue-jeans.

- James Alexander, The American Mechanic and Working-Man, Vol I, New York: William S. Martien, 1847, 35.

- Statistics of the United States, Chapter 5 [partial citation available online, c. 1850] 82. www2.census.gov.

Amazing blog! I really enjoy it, <a href="Austin trim“>link text

they have amazing labels, patches, and many more