Meet Madame Olympe! Curator Kevin Jones relays the story behind the mysterious, intriguing southern businesswoman who thrived in a world of male-dominated industry, and survived an internal conflict that threatened to tear this country apart…

The genesis of my knowledge about Olympe Boisse was the donation to the FIDM Museum in January 2007 of this beautiful 1860s gown by jewelry and fashion collector Cathy Gordon. The outfit had recently sold through the Whitaker Auction Company in New Hope, Pennsylvania, in 2005.1 Made from black silk faille brocaded with flower sprays of violets, bachelor buttons, red poppies, white daisies, white roses, purple asters, lilies-of-the-valley, and bleeding hearts, it is trimmed with floral-patterned silk ribbons, floral-enameled buttons, and an unusual polychrome fringe edging the neckline.

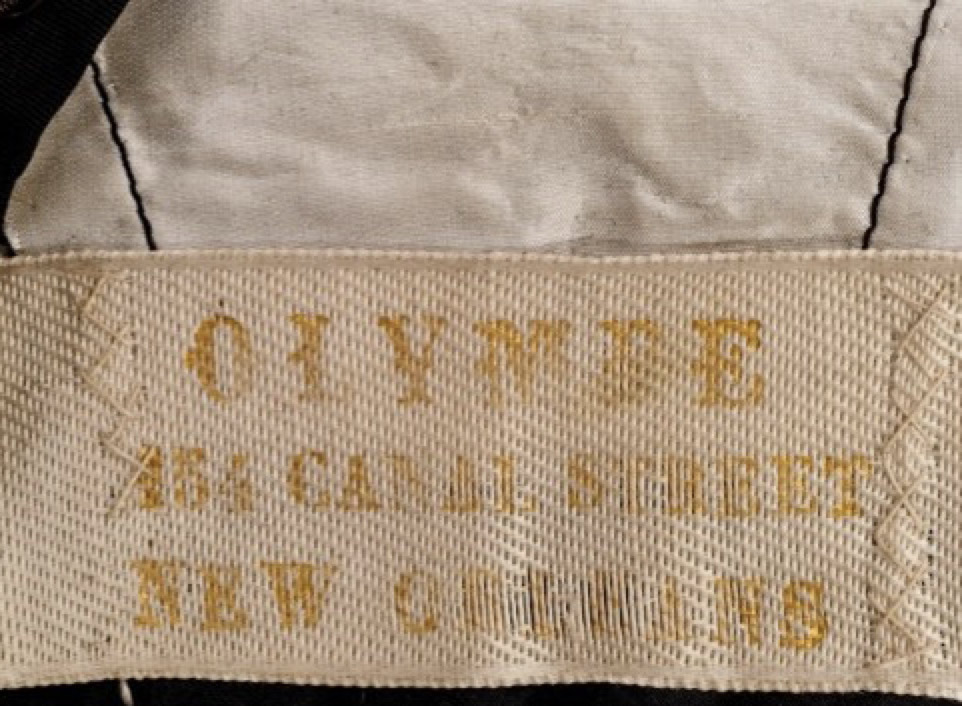

What makes the FIDM Museum gown so rare, though, is that its bodice petersham—an inner ribbon waistband—is labeled “Olympe.” Most of us are familiar with the famous “man-milliner” Charles Worth who with business partner Otto Bobergh established what is generally considered the first haute couture house in Paris, France, in 1858.2 Sometime in the early 1860s, Worth & Bobergh added a stamped gilt name to its petershams, a brilliant marketing strategy soon copied by other fashion houses, including Olympe. Historically speaking, labeling had been around for a hundred years, most often in accessories such as hats and shoes.3 However, precious few garments bear identification prior to the 1870s, and most of them have French addresses.4 The FIDM Museum ensemble stands out from other early-labeled garments because of its printed address and city of origin: 154 Canal Street, New Orleans. This gown is one of the oldest American-labeled garments, but as we shall see, it is actually more closely related to its French cousins than its American roots suggest.

So who was “Olympe” and where did this outfit originate? The dress was donated to the Denver Art Museum in 1958, and soon thereafter was published in its quarterly journal as a highlight of the costume collection.5 Unlike accepted display practices today, live modeling of historic garments was then a typical way of bringing them back to life, but this often resulted in alterations and damage to the garments. In this case, the skirt waistband was reset, which threw the balance of the skirt off slightly to the proper left, and, inexplicably, it was lined in a synthetic organza; perhaps to strengthen the garment for additional wearing. The lining has since been removed and the waist re-pleated into a more period-appropriate configuration. Interestingly, a tucker of machine lace was tacked onto the low center-front neckline of the bodice, providing modesty for the model and revealing a less relaxed standard of propriety a hundred years after the gown was created! The tucker has also been removed and otherwise the bodice was not altered, though a pleated, floral-patterned silk ribbon encircling the proper-right wrist is now missing.

According to Denver Art Museum provenance records, the gown was originally owned by a “Miss Mary May,” but her identity remains a mystery, as does the circumstance when the dress was first worn.6 A spurious, romantic story notes that Miss May danced in the outfit with none other than Edward, Prince of Wales, at a ball held in his honor in New Orleans in the fall of 1860.7 The seventeen-year-old prince was the first member of the British royal family to visit North America on a good-will mission representing his mother, Queen Victoria. Among the U.S. cities on his itinerary were Boston, New York, Pittsburgh, Washington, D.C., and New Orleans.8 But this story cannot possibly be true on three accounts: 1. The unaltered bodice stylistically dates to the later 1860s; 2. The bodice style is less formal than required for such an important social function as a ball for European royalty, though there once may have been a coordinating ball bodice; and, most importantly, 3. Olympe was not at 154 Canal Street until December 1865 (a point that I will come back to later). Unfortunately, nothing more is known about the ensemble, but there is a great deal to be learned about its creator.

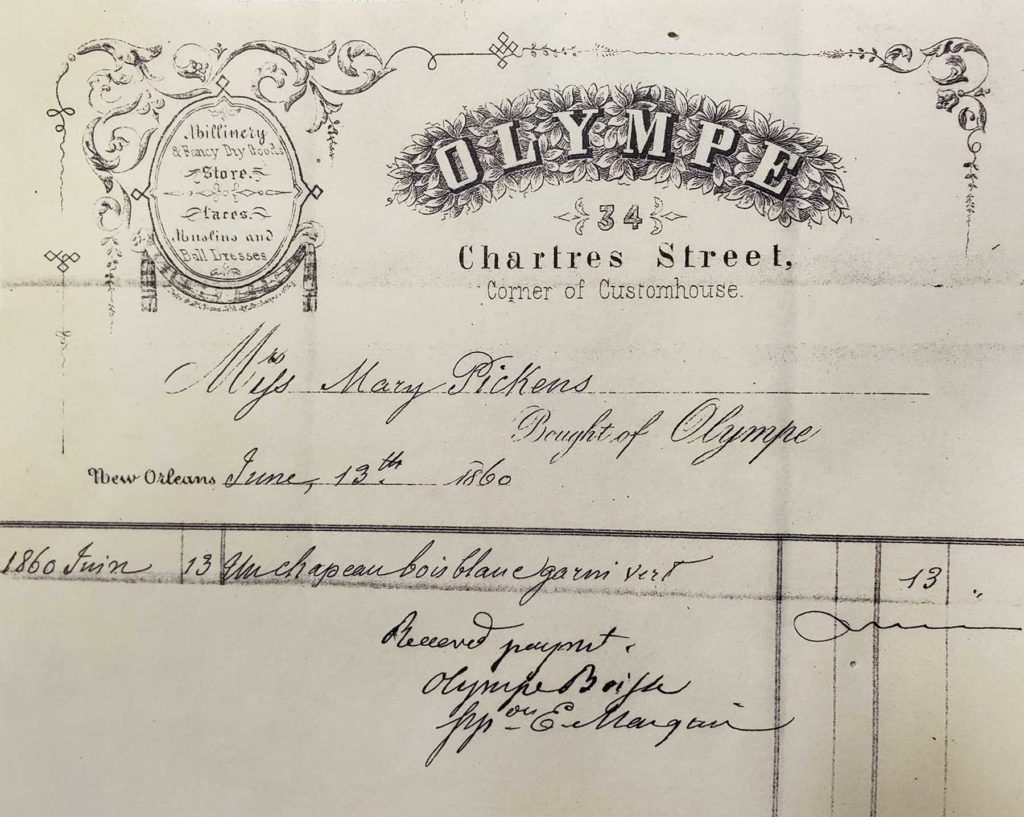

Olympe Boisse was a French native who probably immigrated to the U.S. in the 1840s. The Louisiana Census of 1850 records her as living in a single-family dwelling with six other women and lists her age as 28, placing her birth date about 1822.9 Confusion arises, though, because both the 1860 and 1880 censuses document her birth year as 1830 (possibly falsified for the sake of vanity?).10 Whichever is correct, in 1853, Olympe took over the successful New Orleans millinery establishment of A. Mace at 34 Chartres Street “selling nothing but goods of the finest and richest quality.”11 Mace had been in business since 1845 importing French millinery and “fancy dry goods,” and, according to the 1849 census, had “a husband in France & a lover here.”12 Mace died in 1853. Olympe changed only the name of the store, but maintained its quality of merchandise, customer base, and importing practices.

In 1854, Mademoiselle Boisse married Frenchman Émile de la Grange and was thereafter known in business circles as “Madame Olympe.” Her husband was not part of her enterprise. However, Olympe did take on a male partner, Germain Ducatel, who handled the day-to-day operations of the Chartres Street shop leaving time for her to travel to and from Paris where she acquired the tempting delights enjoyed by her customers.13 She had a keen eye for the stylish, maintaining “the most brilliant and fashionable store in the city” and “always [had] a rush of customers.”14 By 1858, Olympe expanded beyond millinery and began importing laces, muslins, ball dresses, and “ladies furnishing goods,” selling her imports “at very large profits.”15 Ducatel stayed with her until 1860 when they dissolved their business relationship by mutual consent. All-in-all business was brisk and Olympe was listed in every business directory (except 1854, the year she was married) until 1862, the year of the blockade.

Beginning in 1861, the war-between-the-states slowly wrought havoc on the lives of every American, particularly in the South where most of the fighting raged. Southerners were an agrarian society used to importing goods and were soon feeling the effects of northern restrictions—particularly New Orleans, a primary target seized by the Union army in 1862.16 In April 1863, a J.B. Jones noted, “Pins are so scarce and costly, that it is now pretty general practice to stoop down and pick up any found in the street.”17 The Confederacy quickly realized that without the skill and daring of blockade-runners, the Yankees would effectively halt all communication with foreign ports. An estimate 8,000 round trips were made by a fleet of 1,650 vessels along the 3,500 miles of southern coastline with 189 harbors and inlets.18 But the South was still losing the war, and possibly because of fashion. Due to the traffic in luxury goods instead of badly needed military supplies, in February 1864, the Confederate Congress passed a law requiring permits (!) for blockade running and limiting imports to necessities. One Richmond newspaper lamented, “No more watered silks and satins; no more Yankee and European gewgaws; nothing but Confederate sackcloth!”19

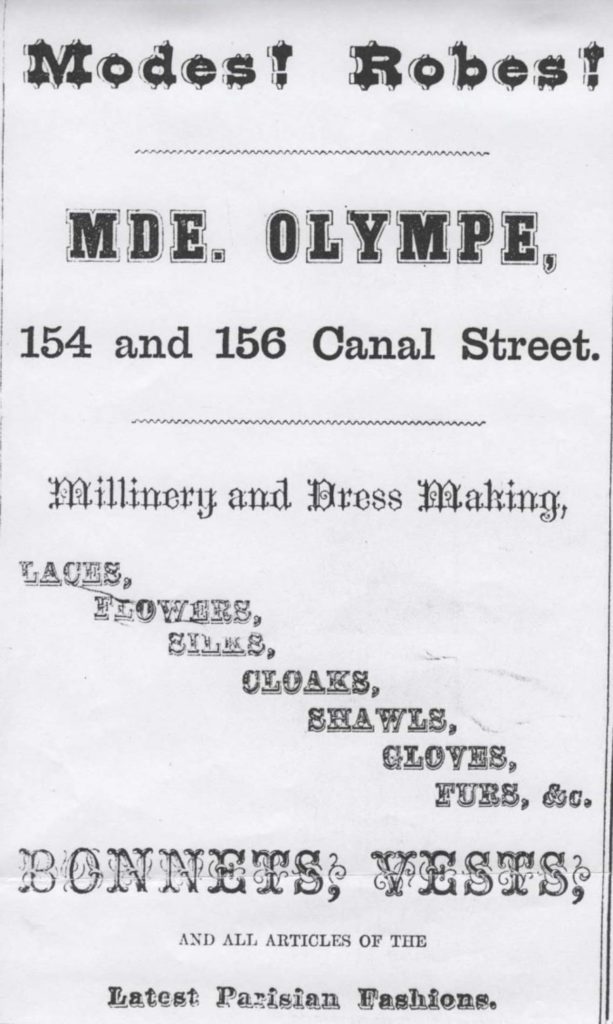

Likely due to the circumstances of war, there are no city directory listings for Madame Olympe between 1862 and 1864. It is unknown if she even stayed in the city. With property in France, it may have been tempting to wait out the war in her native land. Aside from the blockades, the war introduced other importing difficulties that would affect Olympe’s business for years to come. First in 1861, and then again in 1864, the Federal government substantially increased taxes on imported silk goods to an average of 60 percent (remaining virtually unchanged until 1883) in an effort to raise much-needed revenues for the Union treasury. Interestingly, these taxes became unintentional protective tariffs on the fledgling American silk industry.20 Despite these difficulties, and the fact that the South was in ruins, by war’s end in 1865, Olympe was listed in the city business directories as “making money.”21 She signed a five-year lease for new premises at 154 and 156 Canal Street in May 1865, and moved in the following December—”No better location in New Orleans.”22 According to contemporary social historian Eliza Ripley, it was an astute business decision as Canal Street was “more commodious and less crowded…Olympe, the fashionable modiste, was the venturesome pioneer.”23 Probably prompted by the soon-to-expire lease and a lawsuit brought by her landlord for unauthorized interior construction, she moved again in 1869 to 144 Canal Street, formerly the Maison Doré restaurant.24 Though Olympe had been a successful businesswoman for 15 years, the period of Reconstruction proved challenging.

Olympe’s standing in the business community was exceptional. In hard-to-read but beautifully scrolled penmanship, the city’s 1871 directory repeatedly praises her work ethics: “Very prompt to meet all obligations…Stands well and in good credit, is honest reliable woman…An honest straight forward good woman.” But for the first time there is also a sobering note: “Not making much money.”25 Such a remark was not a slight to Olympe personally, but more an observation of how the business world had changed since the Civil War. The South was under military occupation, silk goods (her specialty) were heavily taxed, and New Orleans experienced epidemics of cholera, scarlet fever, smallpox, typhoid fever, typhus, and yellow fever.26 The challenges were great indeed and similar business notations continued throughout the 1870s.27 In 1883, the building she leased was sold and there was yet another move, this time to her final place of business at 110 Canal Street.28 In the same year, the city directory mentioned that Olympe was shipping goods from New York, suggesting that her trips to Paris were less frequent, probably to help defray some of the exorbitant import taxes and to keep her store stocked with fashionable merchandise (New York had long since surpassed New Orleans as a fashion capital).29 It is possible that Olympe was now working solely to keep her doors open and maintain her impeccable reputation. Nevertheless, the end finally did come and Madame Olympe closed her business of 30 years sometime between 1885 and 1886.30

Sadly—especially for dress historians—there are precious few surviving examples of Olympe’s work. At this date, only two other complete ensembles are known: a pink moiré dress with day and evening bodices dating to ca. 1866 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a late-1870s cream satin wedding gown stripped of its lace trimmings in a private collection.31 The Louisiana State Museum owns one labeled bodice with draped overskirt of green brocade worn by Elizabeth Poitevent Holbrook at her second marriage in 1878.32 She was a prominent New Orleans businesswoman known as “Pearl Rivers” who published the Daily Picayune from 1876 to 1895. The only other labeled objects are two fans: one in its original box in the Louisiana State Museum and the other in The Historic New Orleans Collection.33 A bodice supposedly worn by Confederate First Lady Varina Davis and a cream point-lace scarf are two associated objects, though neither is labeled.34 Even with so few examples, it can be surmised that Olympe attracted patrons who were not only fashionable, but also prominent in business and politics. What could be better than to dress the very woman who reported the latest social, political, business, and fashion news of the city? Additionally, to dress the wife of the southern president would have been as important for Madame Olympe as it was for Charles Worth to dress the wife of the emperor of France. With no known documented images of either Olympe herself or her dressed clients, only contemporary literature and court records give a sense of how she interacted with her patrons, how much she charged, and descriptions of her merchandise.35

New Orleans appeared to be a venturesome city when it came to sartorial display. Author John Mackie noted in his 1864 book From Cape Cod to Dixie and the Tropics that “nowhere in all its course does the American sun behold so high-colored muslins, such flaunting silks and roseate ribbons. New York has no show of millinery to compare with it.”36 However, Madame Olympe most likely did not create the objects she sold. She probably purchased from Parisian textile and fashion houses the materials needed for bonnets and headdresses—in addition to completed examples—and model dresses of paper or muslin patterns for her seamstresses to use as guides for adaptations in materials desired by her clients.37 Eliza Ripley observed that Olympe was really more of a flatterer who “did not—ostensibly, at least—make or even trim chapeaux. Olympe’s ways were persuasive beyond resistance” and she “met her customer at the door with ‘Ah, madame’—[I have] brought from Paris the very bonnet for you! No one had seen it…an inspiration!”38 The client was hooked and the object of desire was soon in a box ready for delivery. Olympe was an entrepreneur, as well, developing costly merchandising techniques that added a luxurious touch to a general shopping expedition: “Mme. X had her special bonnet sent home in a fancy box by the hand of a dainty grisette. Olympe was the first of her class to make a specialty of delivering the goods. And Monsieur X, though he may have called her ‘Old Imp,’ paid the bill with all the extras of specialty and delivery included, though not itemized.”39 This selling technique probably explains why a gown bought for $100 by Lovel Ledoux, Sr., was invoiced for $200: the basic dress cost was quoted to this father unfamiliar with shopping for his daughter, but the ribbon and lace trimmings—and “special” delivery charges—doubled its price.40

What did these creations look like? Unfortunately, no known bonnets survive—though they were the specialty of the house. Eliza Ripley briefly mentions complex coverings on head-enveloping poke bonnets: “Light blue satin shirred lengthwise; crêpe lisse, same color, shirred crosswise over it, forming indistinct blocks; and a tout aller, of raspberry silk, shirred ‘every which way’.”41 Ripley also relays the desirability of Olympe’s creations in what is now a racially disturbing account about a purloined bonnet and two enslaved girls overcome by temptation due to the beauty of their mistress’s bonnet: “See the satin strings! And just look at the cape at the back! And the feather poppies! It was of the ‘skyscraper’ shape, made on stiff millinette, that is more easily broken than bent. Mashed sideways, it showed in its flattened state as much of the satin lining as of velvet cover.”42 Incidentally, the bonnet cost $20.00, not an insignificant sum.

Generally, how expensive were Madame Olympe’s creations? Recollections vary. John Mackie recorded the gossip coming from the fashionable St. Charles Hotel: “You hear it whispered about, that the dress of white point lace worn by the young belle standing before you cost papa two thousand dollars. Yonder miss has hidden herself in the corner, because, for the embroidered muslin she has on, Madame Olympe did not charge but two hundred dollars.”43 From an 1862 letter by Marie Villere in New Orleans to her sister Therese Roman at Oak Alley Plantation: “I saw some dresses for you at Olympe for $38 and $46. I found that a little too expensive.”44 Perhaps the price differences had something to do with the war and the blockade of New Orleans harbor that same year. No matter the expense, such creations were deemed necessities, as John Mackie noted: “Every box she [Olympe] orders from Paris produces, when opened, the effect of another Pandora’s, turning half the ladies’ heads in the Mississippi country, and emptying all their purses.”45

Unfortunately, sometime clients’ desires got the better of them. The same Lovel Ledoux, Sr., who ventured into chez Olympe to acquire a dress for his daughter, ended up in a lengthy court case still under appeal five years later over the “fabulous” $1,336.85 invoice that minutely detailed his deceased wife’s many acquisitions between February and October 1865. His claim of ignorance of the purchases did not hold up, he lost the case, and was ordered to pay the balance, interest on the sum, and the court costs.46 And the New York Times headlined an April 1874 lawsuit Olympe brought against Aristide Bienvenu, a New Orleans stockbroker, whose wife also ran up a large bill for millinery and dressmaking. Olympe’s attorney, A.B. Phillips, was “grossly abused and insulted” by Mrs. Bienvenu outside of the Jackson Square courthouse with, apparently, the full support of her husband. As a result, Phillips “knocked him down.” Insulted and no doubt embarrassed by this physical act, Bienvenu challenged Phillips to an illegal duel. The weapons of choice: double-barreled shotguns at forty paces! Ironically, Bienvenu was shot through the head and killed over his wife’s millinery. The reporter did not publish Olympe’s reaction, nor what happened to her lawyer.47

What ultimately became of Madame Olympe after the closure of her lauded fashion establishment is a mystery. Perhaps she moved back to France with her husband to live out the remainder of her life; her death date and burial place are unknown. In the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration conducted gravestone surveys in New Orleans, but no records listed an Olympe Boisse or de la Grange.48 Archives in France may hold the answers.

Acknowledgments

For this research paper, I am acting as a privileged editor of much previously gathered material. Many anonymous volunteers at the Louisiana State Museum combed through city directories over the years and compiled their findings under the leadership of long-time curator Maud Margaret Lyon. Equally diligent in searching out bits of information was Kim Weiss, curatorial assistant to Elizabeth Ann Coleman at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Additionally, thanks goes to Shelly Foote, Julia Long, and Wayne Philips.

OLYMPE BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Browne, Ray B. and Lawrence A. Kreiser Jr. The Civil War and Reconstruction. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2003.

- Catton, Bruce. The American Heritage Picture History of The Civil War. New York: American Heritage Publishing, Co., 1960.

- Coleman, Elizabeth Ann. The Opulent Era: Fashions of Worth, Doucet and Pingat. Exh. Cat. New York: The Brooklyn Museum of Art, 1989.

- Dunham, Lydia Roberts. Denver Art Museum Costume Collection. Denver: Denver Art Museum Quarterly, 1962.

- Field, Jacqueline and Marjorie Senechal, Madelyn Shaw. American Silk, 1830-1930: Entrepreneurs and Artifacts. Texas: Texas Tech University Press, 2007.

- Gardner’s New Orleans Directory. 1868.

- Laborde, Peggy Scott and John Magill. Canal Street: New Orleans’ Great Wide Way. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., 2006.

- Louisiana Census, Roll M432-235, 23.

- Mackie, John Milton. From Cape Cod to Dixie and the Tropics. New York: G.P. Putnam, 1864.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Chronicles of the Civil War, 1861. New York: MacMillian Publishing Company, 1989.

- New Orleans Business Directory. Vol. 9. Boston: Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- New Orleans Business Directory. Vol. 11. Boston: Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- New Orleans Business Directory. Vol. 12. Boston: Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- New Orleans Census. Louisiana: 1860 & 1880.

- New Orleans City Directory, 1877, 1886.

- Parmal, Pamela A. Fashion Show: Paris Style. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2006.

- Ripley, Eliza. Social Life in Old New Orleans: Being Recollections of my Girlhood. New York and London: D. Appleton and Company, 1912.

- Tallant, Robert. The Romantic New Orleaneans. Dutton: 1950.

- The New York Times. New York: April 5, 1874.

- Thieme, Otto Charles and Elizabeth Ann Coleman, Michelle Oberly, Patricia Cunningham. With Grace & Favor: Victorian & Edwardian Fashion in America. Exh. Cat. Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum, 1993.

- Tozer, Jane and Sarah Levitt. Fabric of Society: A Century of People and their Clothes, 1770- 1870. Wales, Scotland: Laura Ashley Limited, 1983.

- Whitaker Auction, Lot 827[November 19, 2005]. See also Parmal, 208 (Note: 53).

- Elizabeth Ann Coleman, 12.

- Tozer, 112.

- Thieme, 94 (Note: 6).

- Dunham, 26-27.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Louisiana State Museum clipping file.

- Louisiana Census. Roll M432-235, 23. (Brooklyn Museum clipping file).

- New Orleans Census, June 1860. & June 1880. (Brooklyn Museum clipping file).

- New Orleans Business Directory Vol. 11, 9. (Louisiana State Museum clipping file).

- Ibid. Vol. 9, 18. (Brooklyn Museum clipping file)

- Ibid. Vol. 11, 9.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Catton, 171.

- McPherson, 171.

- Catton, 203.

- Ibid.

- Field, XXII & 266.

- New Orleans Business Directory Vol. 12, 121. (Louisiana State Museum clipping file).

- Kunemann v. Boisse, 19 La. Ann. 26 (January 1867), Louisiana Supreme Court, No. 1007, https://cite.case.law/la-ann/19/26/ [March 31, 2022]. And Ibid: New Orleans Business Directory Vol. 12.

- Ripley, 58.

- New Orleans Business Directory Vol. 12, 121. (Louisiana State Museum clipping file).

- Ibid.

- Browne, XVI.

- New Orleans City Directory, 1877 (Louisiana State Museum clipping file).

- New Orleans Business Directory Vol. 12, 384. (Louisiana State Museum clipping file). See also: Tallant, 223.

- Ibid. Vol. 12, 384.

- New Orleans City Directory, 1886 (Louisiana State Museum clipping file).

- Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. H. E. Rifflard, 1932. Accession: 2009.300.3009a–d.

- Louisiana State Museum, Gift of Mrs. Ashton Fisher & Mrs. Carl Corbin, 1981.122.40.

- Louisiana State Museum, M248; The Historic New Orleans Collection, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1966.13.

- Louisiana State Museum, Gift of Mrs. Paul B. Leeds, 5050; and Gift of Mrs. Rene T. Beauregard, 7223.

- Alva Erskine Vanderbilt Belmont (née Smith) wrote in an autobiography that during her childhood in Mobile, Alabama, her mother, Phoebe Desha Smith, order clothing from Olympe twice a year for herself, Alva, and her sister, and that there was much anticipation of unboxing the packages. Elizabeth L. Block, Dressing Up: The Women Who Influenced French Fashion (Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: The MIT Press, 2021), 18. See Chapter 2, Citation 18: Alva E. Belmont, Alva E. Belmont Memoir, 1917, Matilda Young Papers, Rare Book Manuscript and Special Collections Library, Duke University, Durham, NC, 30-31. The birth and death dates of Olympe, and birth location, noted in Dressing Up are not correct; presently, this information is unknown.

- Mackie, 159.

- Parmal, 54.

- Ripley, 60.

- Ibid.

- Olympe Boisse, Wife, Etc., Respondent, versus Lovel Ledoux, Appellant (January 27, 1870), Supreme Court of Louisiana, No. 2597, [March 31, 2022].

- Op. Cit., Ripley, 61.

- Ibid. 228-229.

- Mackie, 160-161.

- Translation from French (?) into English. (Brooklyn Museum clipping file).

- Mackie, 160.

- Op. Cit., Olympe Boisse, Wife, Etc., Respondent…

- The New York Times. April 5, 1874: 1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Notation in letter to Kim Weiss at the Brooklyn Museum from Rose Lambert at the Louisiana Historical Center, February 1, 1988 (Louisiana State Museum clipping file).

Fascinating! And with family from NOLA & France..

Leads me to want to know more!

Love the HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION. FRANCES JUMMONVILLE was always a great help

Thank you,

Jacquelyn Goudeau

Bay Area, Ca

I have some fabric labeled “from a dress made by Olimpe, Canal Street, New Orleans” which belonged to my great-great-grandmother, E J Phillips who was an actress in New Orleans 1868-1869 and 1871-1875. There’s an image on my website https://www.maryglenchitty.com/clothes.htm and a little information. Thanks so much for your terrific article and research. I’m trying to write a biography of her and working on the New Orleans chapters now. Mary

How fascinating–thank you for sharing with us & good luck with your biography!