FIDM Museum Registrar Christina Frank shares her research on the life and work of Fabrice Simon, the fashion designer celebrated for his dazzling evening wear.

In 1986, the Baltimore Sun ran a headline, “Top American Designers Dream Up Fashions for Diana’s Visit to the States.” The headline and accompanying article were referring to Princess Diana’s hotly anticipated stateside visit. Knowing Diana, the Princess of Wales, to be both fashionable and glamorous, the Baltimore Sun solicited suggestions from American fashion royalty: Geoffrey Beene, Donna Karan, Calvin Klein, Carolyn Roehm, Bill Blass, Arnold Scassi, and the Haitian American designer Fabrice Simon. Most of these designers have remained firmly in the fashion history canon while Fabrice Simon, a Black designer who died of AIDS at the age of 47, has largely been forgotten. In 2022, the FIDM Museum acquired a bright-pink and yellow silk chiffon mini-dress with precise rows of black bugle beads framing an overall pattern of hearts, squiggles, splotches, and backwards math equations, all realized in beadwork. This playful, eye-catching dress prompted the following examination of Simon’s life and contribution to 20th-century fashion.

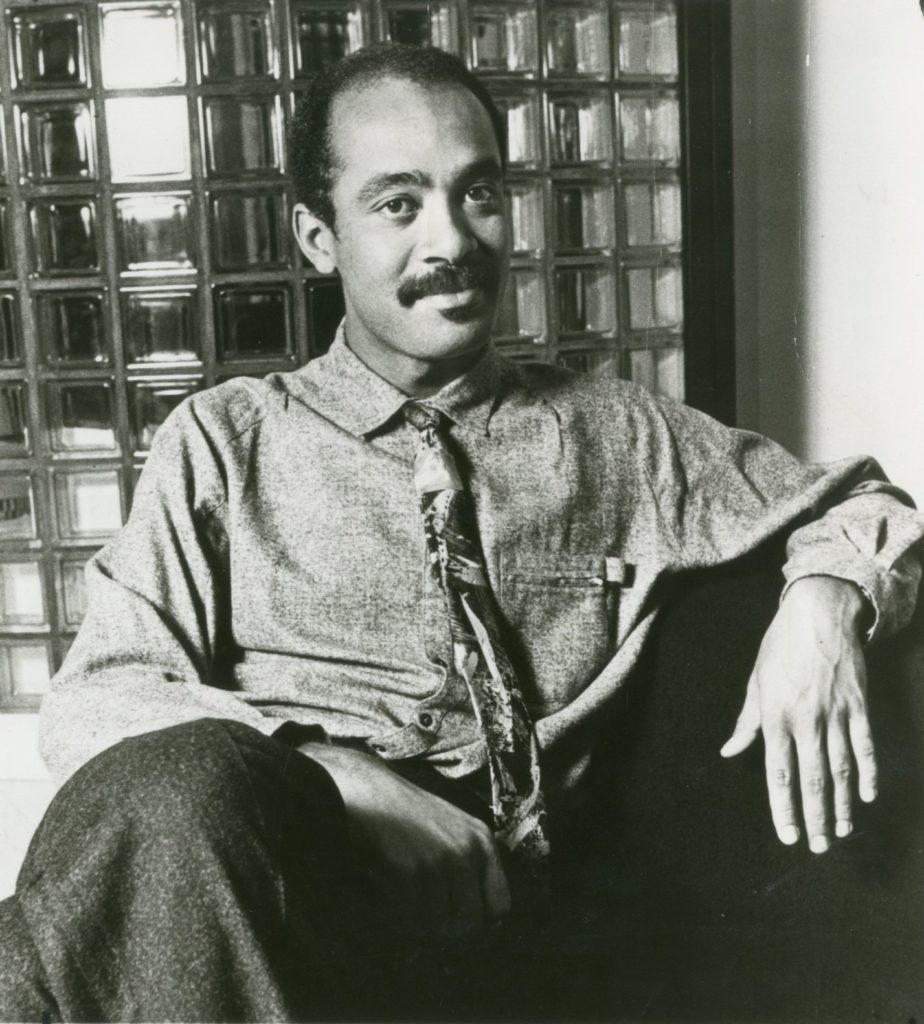

Fabrice Simon was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in 1951. He emigrated to New York with his family as a teenager. Simon attended Flushing High school in Queens; on the recommendation of an art teacher, he began working at the United Merchants and Manufacturers fabric house.1 He left to study textile design at the Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, and returned to the fabric house as a textile and wallpaper designer.2 His next move as an independent fashion designer seems pre-ordained: his grandmother owned a successful couture establishment in Port-au-Prince and his mother worked as an independent dressmaker and seamstress for the American designer Geoffrey Beene.3 Under his given name Fabrice, Simon launched his first collection in 1975, elevating simple, draped garments by painting directly onto the fabric in allover patterns or engineered patterns that spoke to his expertise as a textile designer.4

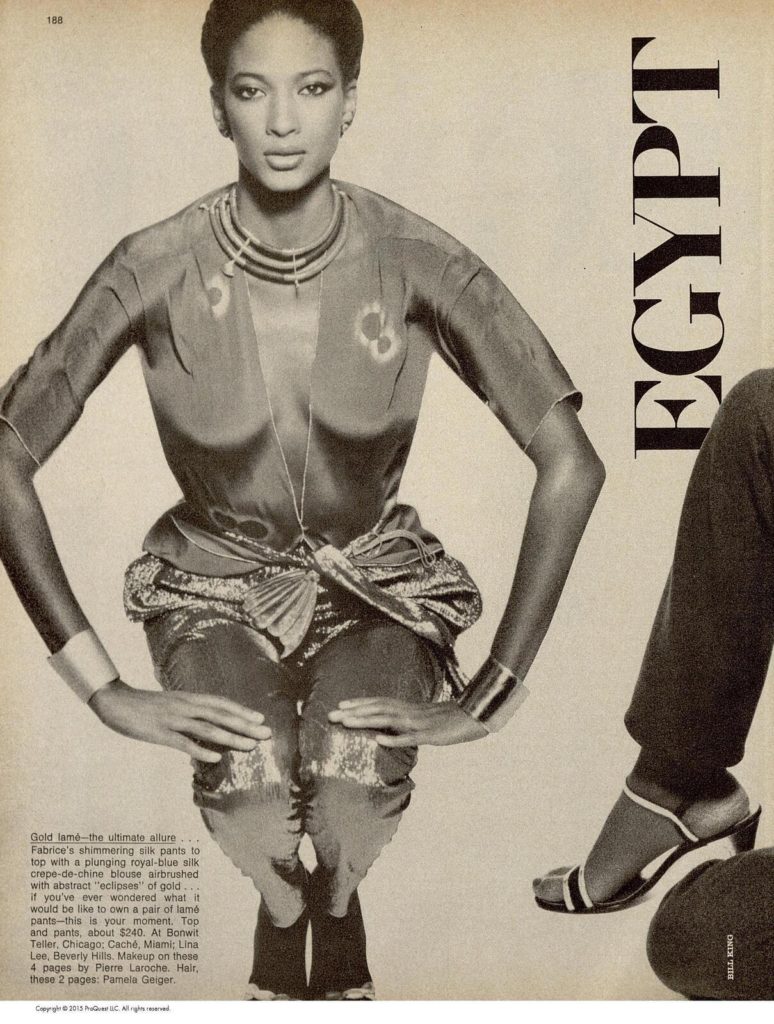

Simon started his brand with an initial personal investment of a mere $3,000. By 1986 his label was grossing over a million dollars a year with 20 full time employees at his factory in Haiti.5 Henri Bendel was the first upscale department store to carry Simon’s work.6 After several years, his practice shifted, and his signature style emerged through a change in medium. He moved from using paint on fabric to “painting” with intricate, dazzling beadwork. Simon credited this new direction to his sister, Brigitte Stiebel, who ran production in the early days of his line. Steibel returned from a visit to Port-au-Prince, Haiti with a piece of beaded fabric and asked her brother to create a gown from it.7

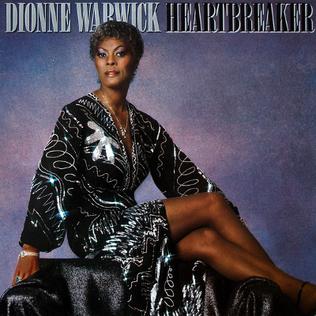

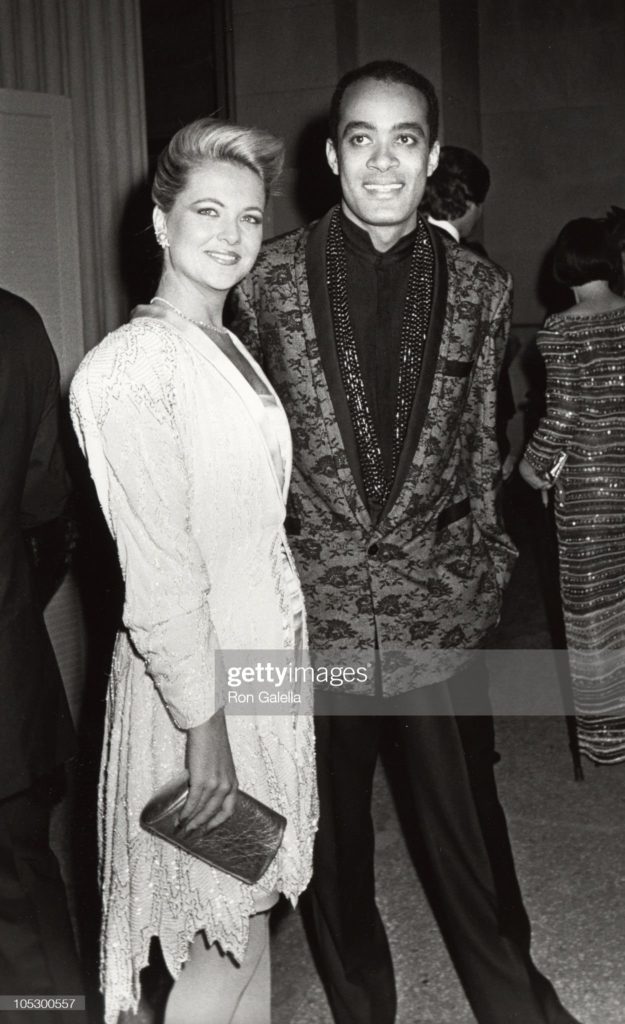

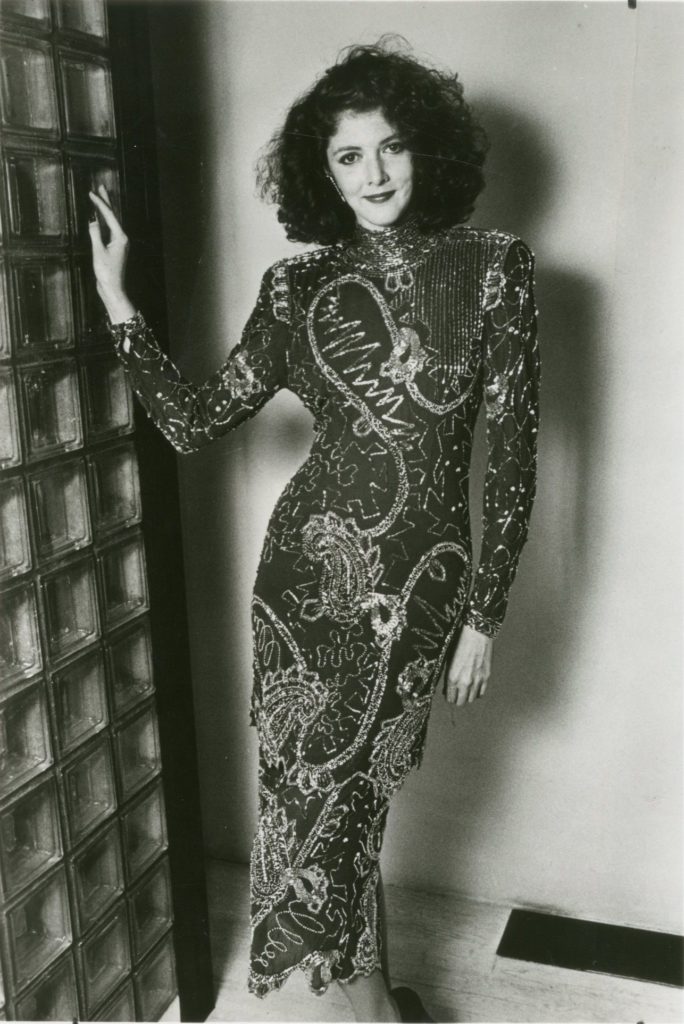

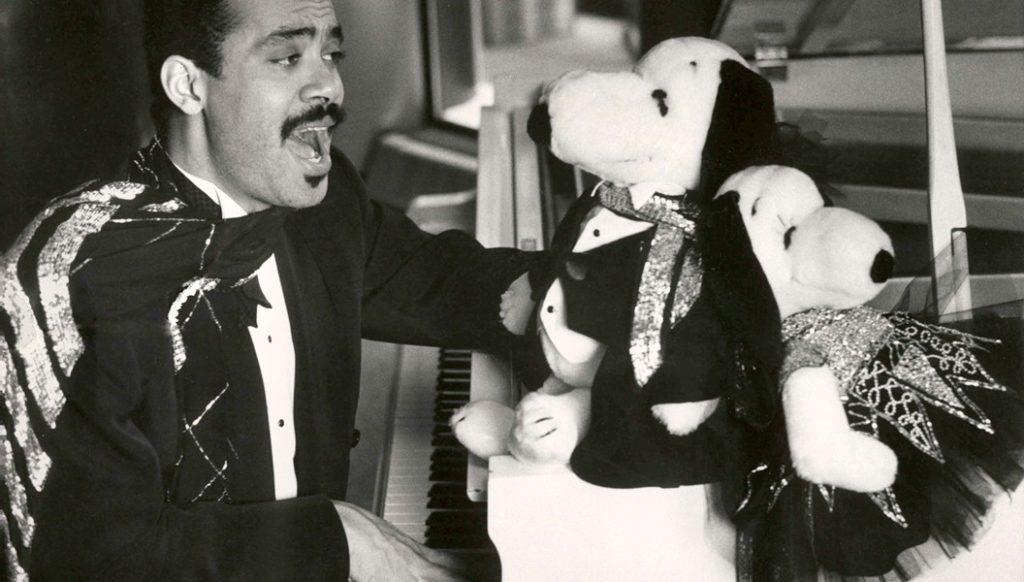

By embracing beadwork, success came relatively quickly to Simon. He was named ESSENCE Magazine’s ‘Designer of the Year’ in 1980 and received a Coty Award in 1981. Simon exclusively designed evening wear, and these dazzling gowns with elaborate beadwork were in heavy rotation by New York City nightlife elites, Hollywood actresses, and pop stars. Simon was close friends with the socialite Cornelia Guest, daughter of CZ Guest, and the two were frequently photographed at hot-spots such as Studio 54–Cornelia glittering in a Fabrice cocktail dress and Simon elegantly standing by.

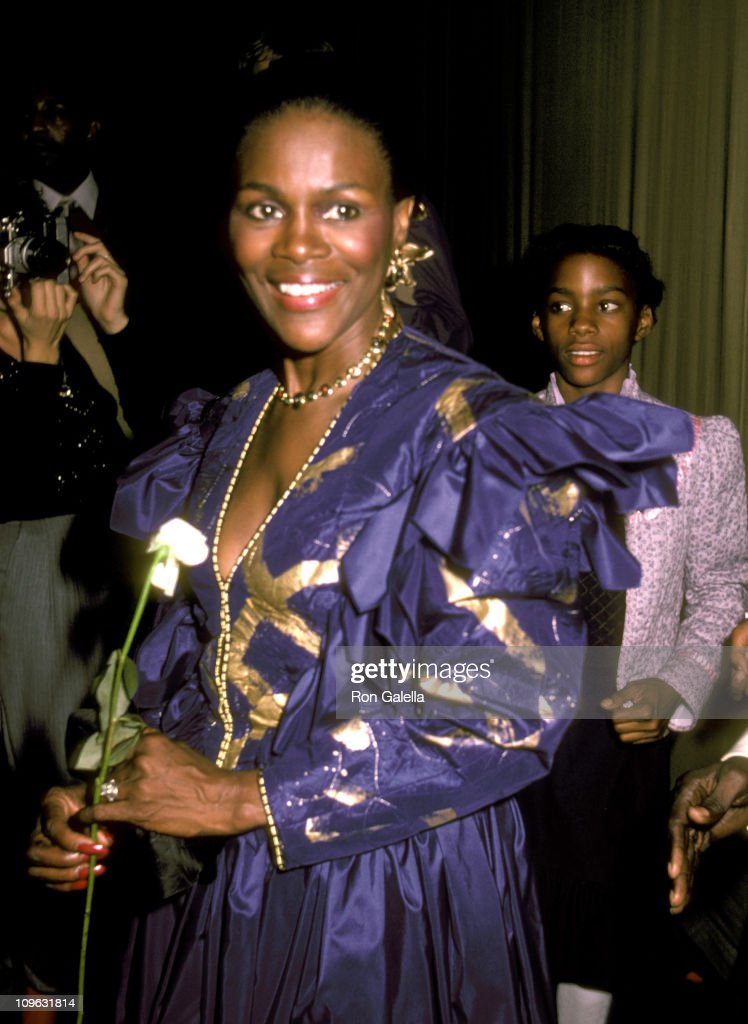

Fabrice’s client list reads like a “who’s who” of the 1980s: Anita Baker, Natalie Cole, Anne Douglas, Morgan Fairchild, Roberta Flack, Nina Griscom, Iman, Eleanor Lambert, Rita Moreno, Veronique Peck, Elizabeth Taylor, Kathleen Turner, Cicely Tyson, and Dionne Warwick all wore and were photographed in Fabrice.8

At first, the label catered to an exclusive clientele: a fully-beaded evening gown came with a price tag of around $8,000. While the fashion press reported on Fabrice’s work, his gowns gained a larger audience through televised events. Whitney Houston famously wore Fabrice to the 1988 Grammys and Shirley MacLaine donned Fabrice when she won an Academy Award in 1984.

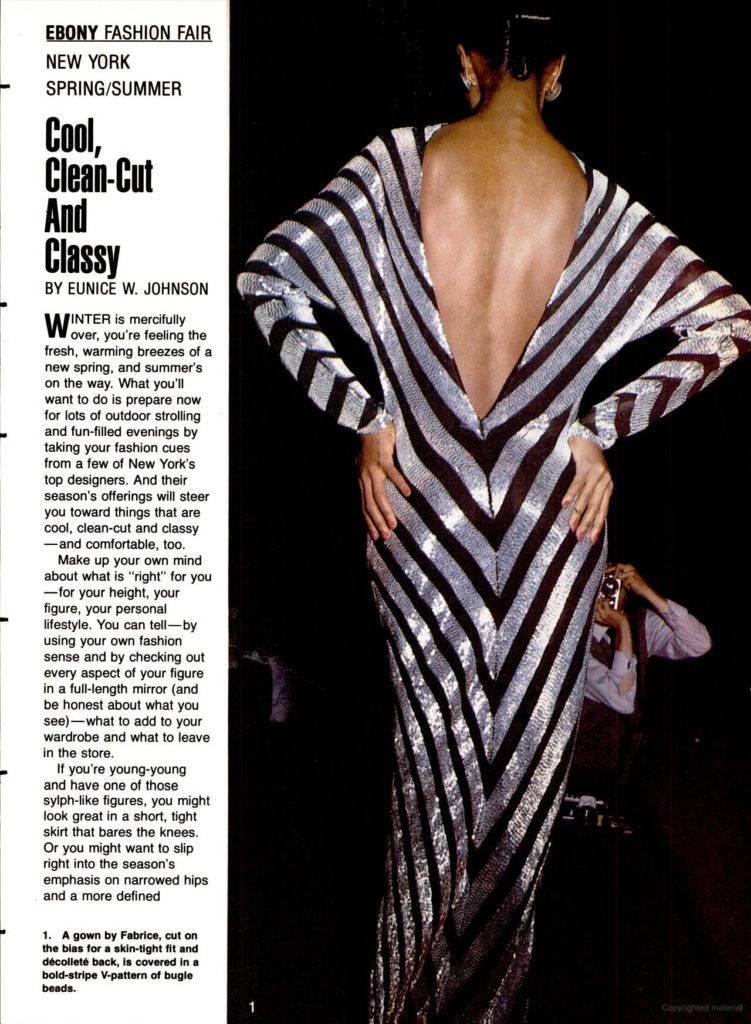

As the label gained traction in the early 1980s, Simon’s parents, who had moved back to Haiti in the 1970s, began overseeing a small factory in Port-au-Prince that produced hand-beaded fabric.9 Simon’s beadwork patterns, often in bold geometric shapes or amorphous swirls, were developed according to the proportion each opulent garment required.10 The beadwork was never without purpose: the strategic pattern lines defined a woman’s figure, reflecting light in all the right places.

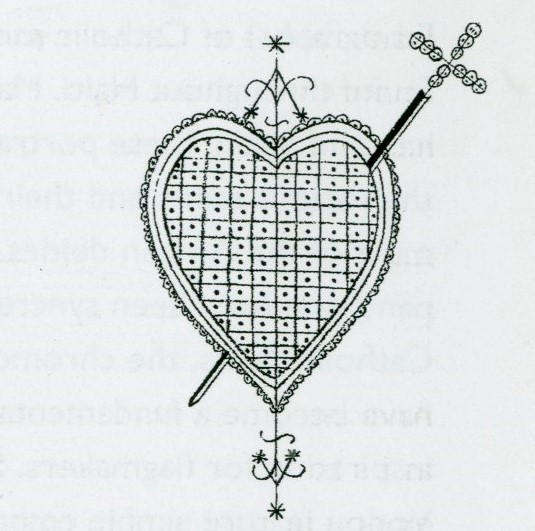

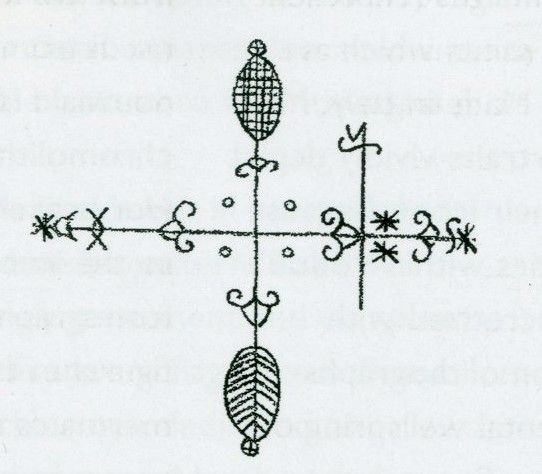

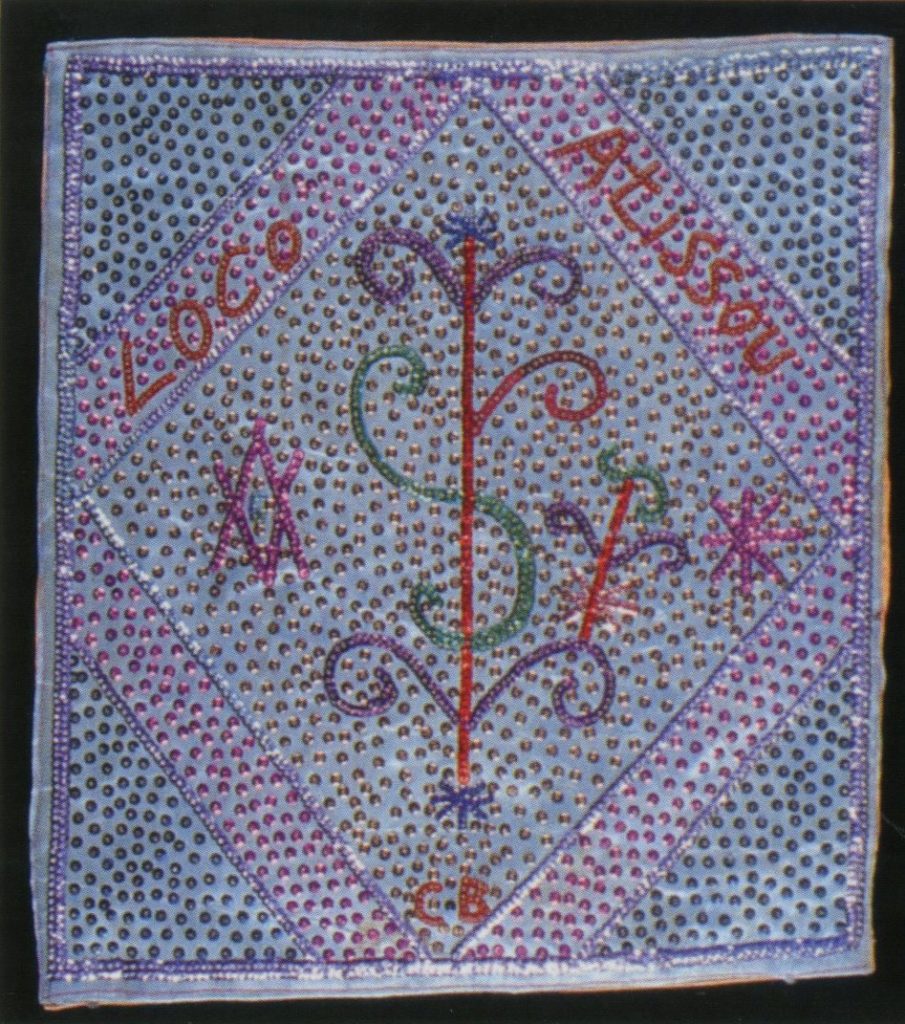

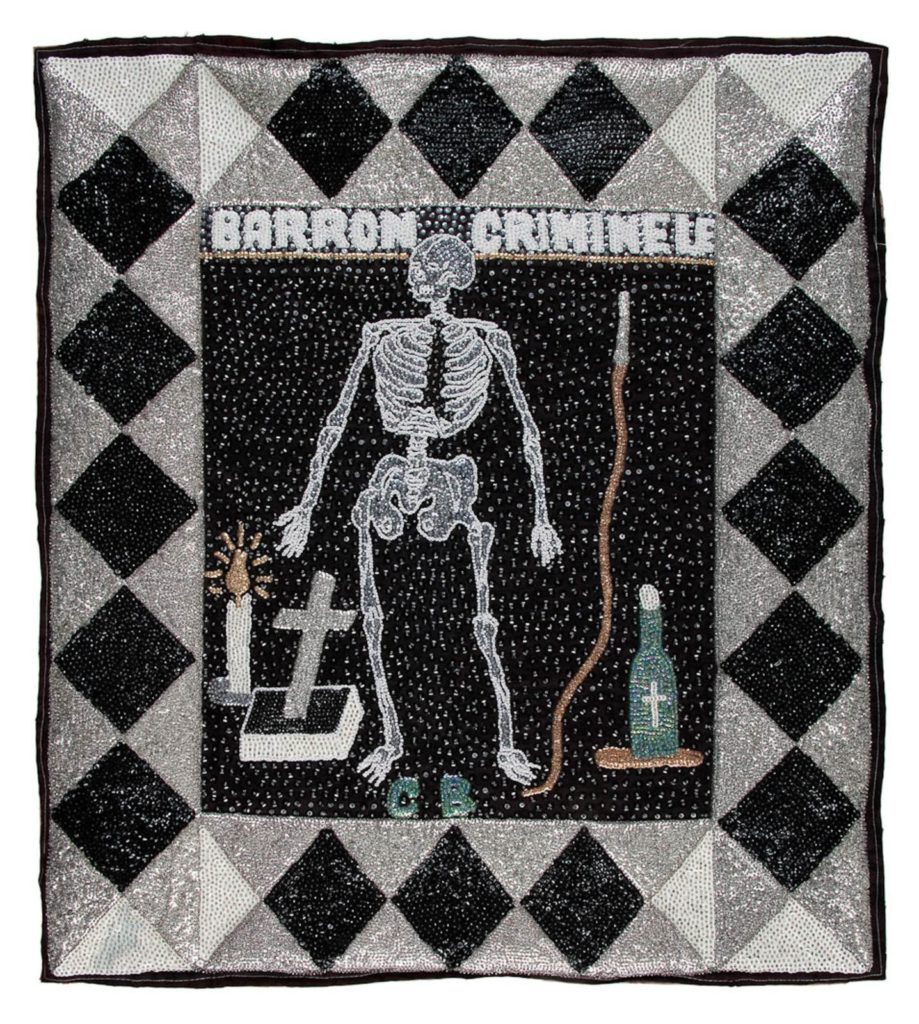

Simon’s beadwork designs were immediately linked to symbolism used in Haitian Vodou, a religion that blends elements of Roman Catholicism with traditional West and Central African religions. Haitian Vodou was developed under slavery and the religion claims the formerly enslaved statesmen and generals who led the 1804 Haitian Revolution into their pantheon of deities known as Iwa.11 During ceremonies, Haitian Vodou priests or priestesses summon these deities or spirits by creating fine-lined, ritual drawings using materials such as oil or ash. Each Iwa is represented by specific imagery. 12 These drawings, or vèvè, are also used to decorate drapo (ceremonial flags and banners) which have become increasingly elaborate over the years.13

More recently, artisans have incorporated allover beadwork and sequins to the flags, many of which are intended for the art or tourist market. Simon’s sister explained that the family grew up surrounded by Vodou imagery, and that the integration of this symbolism into Fabrice’s designs came naturally to him.14 A true family affair, Simon‘s Port-au-Prince factory was established by his sister and operated by his parents. A factory dedicated to the production of beadwork was an anomaly at the time15; however, there were artisans–likely versed in creating flags–that were hired to realize Simon‘s designs.

Of the bead workers he employed in Haiti, Simon said, “the artisans who do my beading were trained in the old tradition, but now share my interest and skills in creating post-modern patterns and textures.”16 Although more research is needed to establish the direct crossover between Vodou artisans and the dressmaking industry, the playful, “post-modern” interpretations of the forms and techniques of Haitian flags is apparent in Simon’s work.17

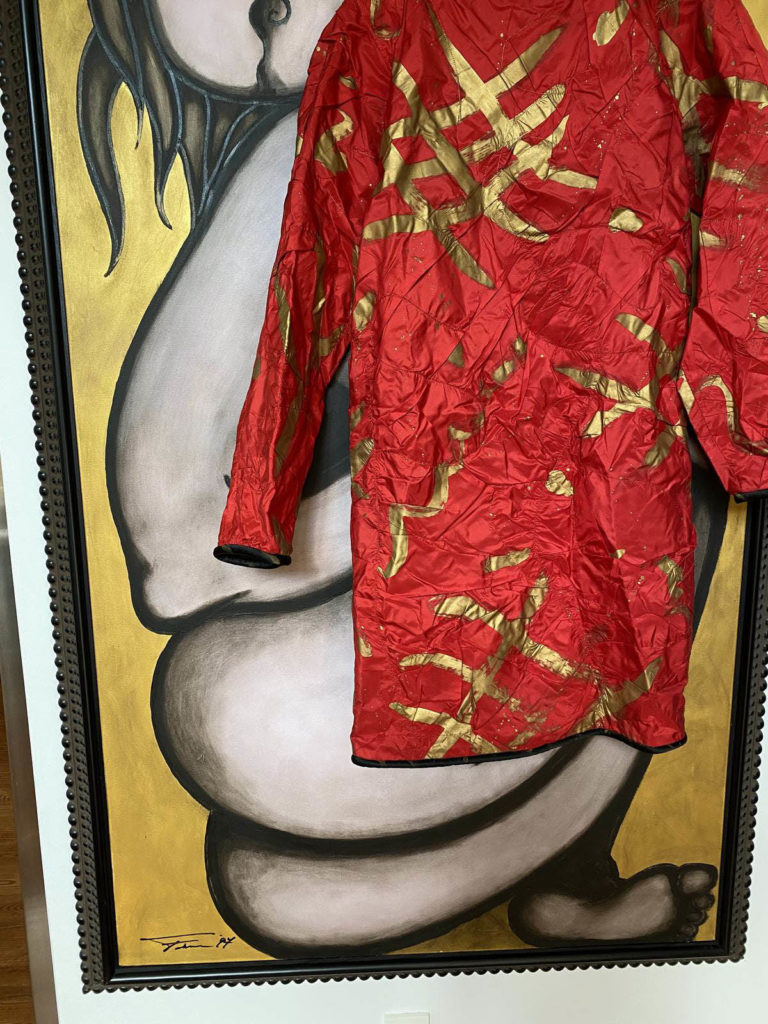

David Nash, an author and collector who has written extensively and passionately about Simon’s legacy, generously donated a Fabrice evening jacket to the FIDM Museum in early 2023.18 This ivory, silk jacket with tone-on-tone bead, sequin, and button embroidery is an excellent example of Simon’s use of Vodou symbolism. The large heart with flourishes, realized in buttons and beads, at center back and on each sleeve references the vèvè for the spirit, Ezili Freda. A flirtatious goddess of love, Ezili Freda represents feminine beauty and luxury–a perfect symbol for a custom-made, hand-embellished garment.19

Other less straightforward, stylistic elements of Haitian Vodou are also present in Simon’s work. Many Fabrice dresses, including the one in FIDM’s collection, feature a defined border or frame that contains the beadwork patterning. This mirrors the practice of drapo artisans who typically incorporate borders into their flags.20

After years dressing socialites and celebrities in his custom and ready-to-wear pieces, Simon’s work attracted the interest of investors.21 In 1989 Simon partnered with the He-ro Group, and began producing two diffusion lines: Fabrice Silhouette, which was designer-priced and Fabrice Graffiti, a more affordable line.22

As part of his licensing deal, Fabrice and his investors had plans to launch lingerie, accessories, and fragrances in addition to his two ready-to-wear lines.23 Sadly, these plans never came to fruition; the He-ro group struggled financially in the early 1990s and Simon, battling health complications due to HIV/AIDS, shuttered his custom and diffusion lines in 1994.

After leaving the garment industry, Simon chose to concentrate on his artwork. Before his death in 1998, his paintings were shown in Palm Beach, Florida and at the James Whyte Gallery in New York City.24 This shift from dresses to canvas was not unexpected. In interviews, Simon repeatedly positioned himself as an artist rather than a fashion designer, treating the fabric (often silk georgette) as a canvas for his creativity. In 1987 he explained to a reporter that his evening wear was, “more art oriented than fashion oriented. I don’t consider myself part of the fashion industry…I don’t just follow. I do exactly what I think is right.”25 While the tiresome debate of whether fashion is art continues, Simon’s fashion designs–influenced by “high” art such as the work of Matisse and Kandinsky along with imagery from his own culture–are undeniably singular artistic expressions.

When Simon passed, Steibel was contacted by a New York Times journalist tasked with writing his obituary. When asked about the cause of death, she responded without hesitation that her brother had died from AIDS.26 While some of the stigma of AIDS has now receded, this type of transparency was extremely unusual in 1998. As Simon’s caregiver, Steibel knew firsthand the ravages of this disease and she elected to spread awareness rather than keep up appearances.

Despite many successes during his lifetime, Simon was largely forgotten. His brand was emblematic of a more carefree and glamorous time, and by the mid-90s, fashion had moved towards minimalism, androgyny, and “grunge” in place of glitz. Today, Stiebel recognizes the racism and homophobia in the fashion industry, noting that Simon “as a Black man, a gay Black man, [meant] we had to work harder.” Unfortunately, this hard work extends to preserving his legacy, something Steibel has attempted to do over the years. While names like Halston and Perry Ellis have been lauded for decades, Simon’s name is finally being recognized; in 2022, Fabrice garments were included in the Costume Institute exhibition, ‘In America: A Lexicon of Fashion,’ and in the Crystal Bridges exhibition, ‘Fashioning America: Grit to Glamour.’ This renewed exposure—or as Steibel termed it, “bringing it to the light”–is something she says would have absolutely thrilled her brother.27

The FIDM Museum favors an object-based approach to research, making the acquisition of pieces from previously overlooked, obscured, or underrepresented designers like Simon so important. In a 1983 interview with People Magazine, Simon mentioned how he started going to museums in his youth to find inspiration.28 While Simon’s life and career were cut tragically short, the hope is that his designs are able to inspire as we, and other institutions and researchers, continue to collect, exhibit, feature, and otherwise make his work accessible.

- Brigitte Stiebel, SImon’s sister, interview by author, January 23, 2023.

- Bernadine Morris, “Fabrice Simon, Not Household Name, Yet! But Glamour Girls ‘Screaming’ About Him,” N.Y. Times News Service, The Times Tribune, September 24, 1983.

- Eleanor Lambert, “Designers Headed for Stardom,” Standard Speaker, January 15, 1983; David Nash, “Fabrice’s Lavish Beaded Dresses Defined 80s Party Culture. It’s Time He Got His Due,” Town and Country, June 23, 2020, accessed November, 2022, https://www.townandcountrymag.com/style/fashion-trends/a32870442/fabrice-fashion-designer/.

- “Fashion RTW: New Find,” Women’s Wear Daily, December 10, 1975.

- Michele Hancock, “Fabrice: Designer Puts Glitter in Spring Wear,” Fort Worth Star Telegram, January 15, 1986; Betty Goodwin, “Fabrice has a Good Bead on What’s Hot,” Los Angeles Times, March 6, 1987.

- Anne-Marie Schiro, “Fabrice Simon, 47, Designer of Glittery Evening Clothes,” New York Times, August 5, 1998.

- David Nash, “Fabrice’s Lavish Beaded Dresses Defined 80s Party Culture. It’s Time He Got His Due.”

- David Nash, “Fabrice’s Lavish Beaded Dresses Defined 80s Party Culture. It’s Time He Got His Due.”

- David Nash, “Fabrice’s Lavish Beaded Dresses Defined 80s Party Culture. It’s Time He Got His Due.”

- Bernadine Morris, “Fabrice Simon, Not Household Name, Yet! But Glamour Girls ‘Screaming’ About Him.”

- Patrick Arthur Polk, Haitian Vodou Flags, (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1997) 10.

- Karen McCarthy Brown,”The ’Veve’ of Haitian Vodou: A Structural Analysis of Visual Imagery,” Temple University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1976, 10.

- Patrick Arthur Polk, Haitian Vodou Flags, 18.

- Brigitte Stiebel, interview by author, January 23, 2023.

- Brigitte Stiebel, interview by author, January 23, 2023.

- Karen Monget, “Making an Entrance? Make it Sparkle with Fabrice,” Palm Beach Daily News, October 29, 1983.

- See the work of Myrlande Constant who worked in a wedding dress factory in Port-au-Prince in the 1990s before using her skills with beadwork to create Vodou flags that are lauded by the art world, https://fowler.ucla.edu/exhibitions/myrlande-constant/.

- David Nash, “Fabrice’s Lavish Beaded Dresses Defined 80s Party Culture. It’s Time He Got His Due.”

- Patrick Arthur Polk, Haitian Vodou Flags, 13-19.

- Patrick Arthur Polk, Haitian Vodou Flags, 21.

- David Nash, “Fabrice’s Lavish Beaded Dresses Defined 80s Party Culture. It’s Time He Got His Due.”

- “Fabrice,47, Eveningwear Designer,” Women’s Wear Daily, August 6, 1998.

- “Fabrice Eyes Future In-Store Shops,” Women’s Wear Daily, January 19, 1988.

- Anne-Marie Schiro, “Fabrice Simon, 47, Designer of Glittery Evening Clothes.”

- Betty Goodwin, “Fabrice has a Good Bead on What’s Hot.”

- Brigitte Stiebel, interview by author, January 23, 2023.

- Brigitte Stiebel, interview by author, January 23, 2023.

- Lee Wahlfert-Wihlberg, “Taking a Bead on Night Life, Designer Fabrice Updates That Old Shimmer and Slither,“ People Magazine, April 25, 1983.