As promised, here is an excerpted portion of Meghan's research on Dracula, which she recently presented at Fashion in Fiction: The Dark Side.

********************************************************************

Since its publication in 1897, Bram Stoker’s Dracula has been interpreted in a variety of ways: as a Victorian Gothic novel, vampire lore, and psychoanalytical expression of repressed sexuality. Beyond genre studies and Freudian psychology, Dracula has become a phenomenon in popular culture. Despite its continual adaptation over the last hundred ten years, the twenty-first century reader should note that the novel is truly a window into the many anxieties and transitions of turn-of-the-century England. Prior to 1897, the British Empire had a long history of spreading its power, values, and, not least of all, style of dress around the globe. While France was certainly the world capital of fashion, establishments such as Redfern and Lucile were equally influential in women’s fashions. Moreover, the somber black suit–the hallmark of the British gentleman-had become the uniform in Western menswear by the late nineteenth century, with very little opportunity for individual statements in pattern, color, or cut. Social norms in dress and etiquette were strongly upheld in England, including in literature; as a result, any variation from these norms would immediately set a character apart in the mind of the contemporary reader.

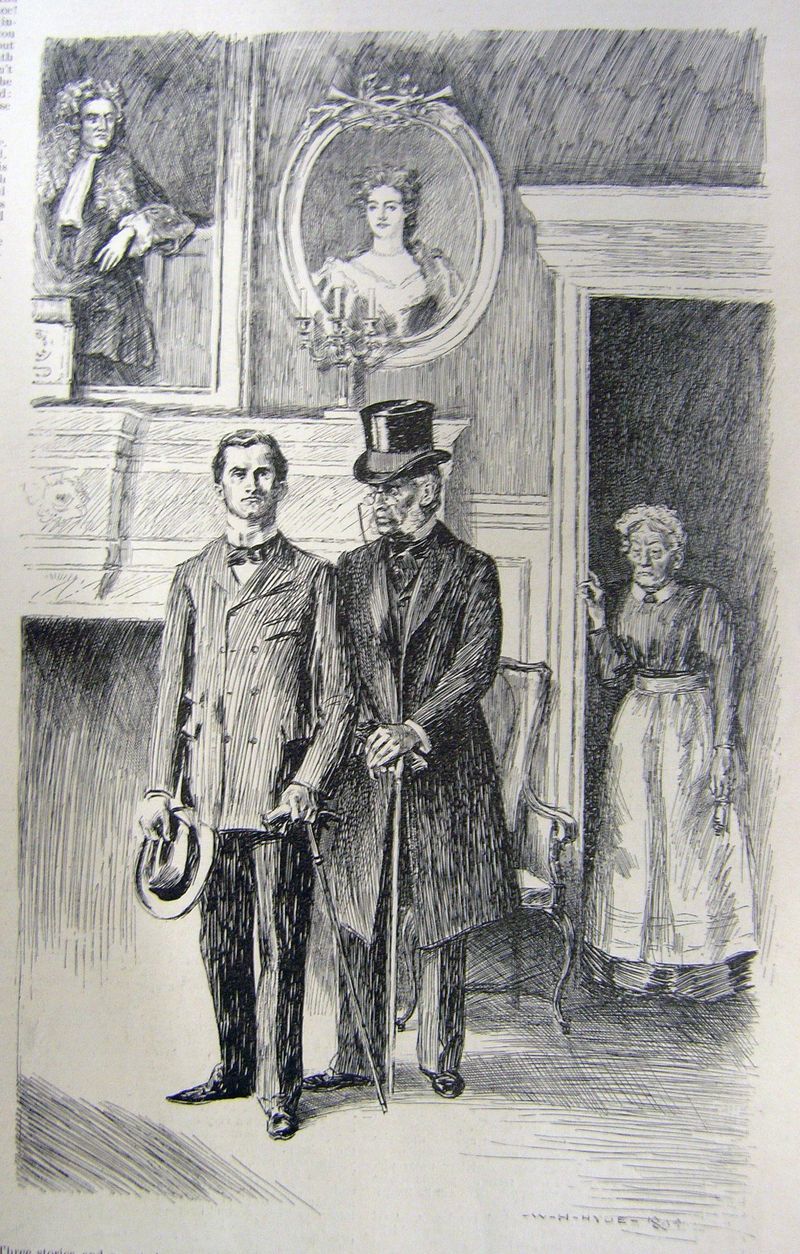

Harper’s Bazar, 21 July 1894, p. 577

Harper’s Bazar, 21 July 1894, p. 577

FIDM Museum Special Collections

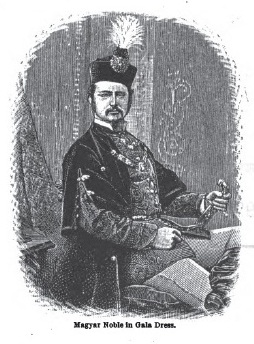

Count Dracula’s sartorial choices reflect a duality of dress as disguise and protection that is prominent throughout the novel. While he is not clothed in a dapper tuxedo with a high-collared black silk cape, as we are accustomed to see in Hollywood adaptations, the limited information provided by Stoker indicates that he is dressed in a Western-style tailored suit. In fact, Dracula’s most valued disguise is to blend in with the masses in London and to not appear foreign; as he explains to his guest, and later prisoner, Jonathan Harker, “Well, I know that, did I move and speak in your London, none there are who would not know me for a stranger…Here I am noble; I am boyar; the common people know me, and I am master. But a stranger in a strange land, he is no one; men know him like the rest, so that no man stops if he sees me, or pause in his speaking if he hear my words, to say, ‘Ha, ha! A stranger!’”1

In 1890s Britain, the most immediate indicator of foreign-ness is undoubtedly the outward appearance of one’s clothing—the English were accustomed to judging minute differences in a man’s ensemble, such as hand-sewing, ready-made versus tailor-made suits, and subtle differences in fabric qualities. Dracula is described as “clad in black from head to foot, without a single speck of colour about him anywhere.”2 Harker makes no indication that Dracula’s garb is outside the norms of English propriety, as he did in regards to the various ethnic groups encountered in his travels. This lack of differentiation indicates that Dracula is dressed in the Victorian man’s uniform: the 3-piece suit consisting of jacket, vest, and trousers, all in black.

“Magyar Noble in Gala Dress”

On the Track of the Crescent: Erratic Notes from the Piraeus to Pesth

Major E. C. Johnson

1885

Harvard College Library, Google Books

Dracula is also able to disguise himself by changing form—most often turning into a bat. The vampire bat was well-known throughout Victorian England as an intriguing, dangerous creature of South America. Through newspaper incidents relating to vampire attacks in Eastern Europe and vampire bats in South America, the English adopted the term ‘vampire’ as a metaphor for unscrupulous businessmen, swindlers, and the like. Only rarely was the term applied to the actual incident of a man drinking human blood. Notwithstanding the negative connotations, bats were a favored motif in women’s fancy dress costumes in the 1880s, as seen in this caricature and this fashion plate. Harker writes in his diary, “I saw the whole man slowly emerge from the window and begin to crawl down the castle wall over that dreadful abyss, face down, with his cloak spreading out around him like great wings.”3 Dracula’s coat foreshadows the bat wings the vampire will subsequently use to flit outside his victim, Lucy’s, window. Dracula’s transformation into a bat is simultaneously deceptive and protective, as it allows the vampire swift escape from enemies while his human form is not associated with the attack of his victims.

The original Dracula had many guises to protect himself and blend in with the crowds of Victorian England, but his image has evolved to something unrecognizable–the caped, European gentleman with dark good looks, or the brooding 20-something in designer clothes–perhaps that is the Count’s ultimate victory!

1 Boyar is the Russian term for the noble class; Leslie S. Klinger, ed., The New Annotated Dracula (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008), 52.

2 Klinger, 42.

3 Klinger, 75.

Dracula has such a cool story around him – I wonder what he would dress/look like these days!