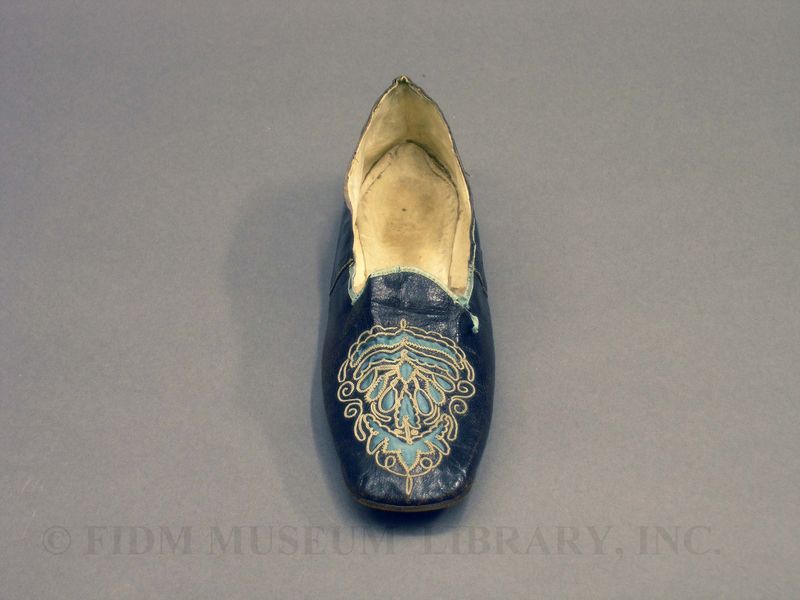

Our Study Collection offers FIDM students, faculty and researchers hands-on access to historic garments and accessories. Objects find a home in our Study Collection for a variety of reasons. Sometimes we have near multiples in the Permanent collection, or a donated object shows signs of age or wear. All Study Collection objects are accessioned because they have something to offer. Though well-worn, this single leather slipper is evidence of a nineteenth century footwear trend while also offering insight into nineteenth century conceptions of public and private space.

Slipper

Slipper

Leather, satin, linen

1850-75

Gift of Steven Porterfield

S2009.897.188

During the second half of the 19th century, strict rules of etiquette dictated appropriate dress. To quote from our blog post on an 1863-65 cotton wrapper, "displaying an understanding of appropriate dress (including accessories) for any given occasion was a way of demonstrating good taste, thus ensuring social standing." Soft leather slippers like those pictured here were worn exclusively indoors. Because they were worn indoors, they have a relatively high survival rate. According to shoe historian Nancy Rexford, the most commonly surviving indoor shoe is that seen here: a slipper of calf or kid with vamp cut-outs backed with pink or blue satin and embellished with machine embroidery. A quick survey of museum collections turned up two pairs with pink or red satin cut-outs: one with low heels, and one flat. This pair features a blue fabric rosette in addition to blue satin cut-outs. Not surprisingly, slippers with a cut-out vamp may have been a revival of an earlier fashion. This pair of 1797 shoes or slippers with blue satin cut-outs on the vamp are remarkably similar and a possible predecessor of the nineteenth century cut-out slipper.

The color of this slipper may differ depending on your monitor. In life, it's a shiny black, though not as glossy as patent leather. This finish was created through a process called bronzing. Many items made of calf or kid leather were bronzed in the nineteenth century, including shoes and gloves. Though I haven't been able to find any information on the process itself, bronzing somehow used the cochineal bug (which also produces a vivid red dye used today in cosmetics) to obtain a slightly metallic or iridescent finish on black leather. Any suggestions regarding where to look for info on the details of bronzing are welcome! Preliminary research unearthed only an 1884 patent for a leather bronzing process using egg white, glycerin and water soaked leather coated with multiple layers of varnish and a metallic finish.1 Given that the egg protein would attract hungry pests and deteriorate over time, any leather goods treated with this bronzing process have probably disappeared.

Slipper Notice that this slipper has a slightly different pattern than the one above.

Slipper Notice that this slipper has a slightly different pattern than the one above.

Leather, satin, linen

1850-75

Gift of Steven Porterfield

S2009.897.187

When researching nineteenth century footwear, the term slipper can be confusing. Slippers referred to both footwear worn at-home and fancy footwear worn to evening functions. To make matters even more complex, a slipper could have either a flat or slightly elevated heel. Most nineteenth century fashion periodicals touch only briefly on footwear, and fashion plates rarely picture shoes or slippers of any type, making it difficult to pinpoint a particular style. When slippers appear in Godey's or Harper's Bazar, it is most often as a DIY slipper pattern to be sewn and embellished as a gift for a friend or family member.

Despite the great variety within nineteenth century slippers, in general, they were worn only indoors. Within the category of indoor slippers were multiple subcategories, including morning slippers, evening slippers and dressing slippers. As was the case with garments, each type of slipper was worn only within its appointed place and time, though there was surely some overlap due to practicality and economic constraints. In 1855, Graham's Magazine unequivocally stated, "slippers, no matter of what material, (we mean dressing slippers), even though they are of velvet, embroidered in gold, should never leave the precincts of the bedroom." Instead, a "neat kid shoe, or a light single-soled boot, should be kept exclusively for the house."2 As bedroom slippers were associated with that most private and intimate of spaces, they were completely unacceptable for other parts of the home. When a woman ventured outdoors, she had yet another pair of shoes to wear, depending on her planned activity. The same delineation between public and private is evidenced in nineteenth century dress. Our c. 1895 morning gown is an example of a relatively private garment worn only at home, specifically in the morning. This strict division between indoor and outdoor dress suggests the Victorian view of the home, as a sanctuary that protected the family from the annoyances and dangers of the outer world. To protect this conception of the home sphere, it was essential to create and maintain sartorial divisions between between garments worn at-home and those worn out in the world.

1 "Miscellaneous Inventions." Scientific American. 12 April 1884; Vol. L., No. 15: 233.

2 "Fashion." Graham's Magazine. June 1855; VOL. XLVI., No. 6.: 577.