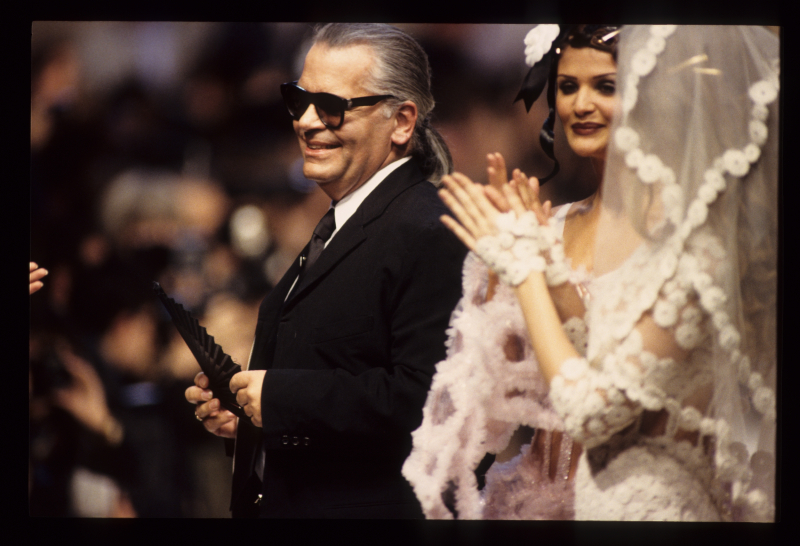

Dark glasses, ponytail, and a crisp starched collar: even for those outside of the fashion industry, designer Karl Lagerfeld (1933 – 2019) was an immediately recognizable self-made icon. Known for his acerbic wit (quoted eagerly in the press) and irreverent attitude, Lagerfeld was the definition of a Renaissance man. His relentless curiosity and quest for knowledge, dedication to art and literature, and voracious collecting – the amassed books in one of his homes is said to have stretched over three miles long[1] – set him apart, but it was his innate understanding of culture and “ability to identify, articulate, and frequently anticipate changes in the zeitgeist”[2] that defined his spectacular career. Lagerfeld’s work for top fashion houses such as Chloé, Fendi, and Chanel proved his creative dexterity, and more importantly demonstrated how to keep fashion (and brand names) relevant over decades of collections: “If all the world changes, you have to change your designs, too.”[3]

Karl Lagerfeld on the Chanel Couture runway

Karl Lagerfeld on the Chanel Couture runway

S/S 1993

Photograph by Michel Arnaud

Gift of Arnaud Associates, SC2000.1095.1

Born to a wealthy family in Hamburg, Germany, Lagerfeld often spoke of the influence his strong-willed mother had on his childhood. It was she who encouraged him to read and converse cleverly from a young age – by his account, his quick and forceful manner of speaking was a by-product of her impatience with listening to his youthful tales.[4] He was perpetually fascinated with fashion, and as a teenager moved to Paris to pursue the field; he got his start at age 21 when he won the 1954 International Wool Secretariat competition in the coat category (18 year old Yves Saint Laurent famously won the same year in the dress category). The competition led to Lagerfeld’s hiring at the couture house of Pierre Balmain, where he stayed for three years before moving to Jean Patou for five years.[5] Enticed by the refreshingly rebellious attitude of ready-to-wear in the 1960s, he left the world of couture to act as a freelance designer for youthful, chic brands including Krizia, Charles Jourdan, and Tiziani.

Evening ensemble on display in Capturing the Catwalk (2018)

Karl Lagerfeld for Chloé, S/S 1984

FIDM Museum Purchase

2009.5.8A-C

It was at Chloé, a French house known for its romantic, bohemian aesthetic, that Lagerfeld learned to become “the shape-shifter”[6] – a designer capable of adjusting his collections to suit the cultural climate. Art nouveau references alternated with outrageous trompe l’oeil surrealist embellishment (as seen in his final S/S 1984 collection, an homage to dressmaking). After working with the house for a decade, Lagerfeld was named the head designer in 1974, a position he held until 1983 – though he returned for a brief period in the mid-nineties to inject his signature brazenness back into the brand. His mantra at Chloé, and perhaps throughout his career, was that “Fashion does not have to prove that it is serious. It is the proof that intelligent frivolity can be something creative and positive.”[7] In the meantime, Lagerfeld had maintained a close relationship with the Italian house Fendi since 1965; he was still designing as Creative Director at the time of his death. Lagerfeld was responsible for creating Fendi’s signature “FF” logo, foreshadowing his frequent use of the interlocking double C’s during his time at Chanel. He has said that the double F’s stood for Fendi Fun, Fendi Fur, or Fun Fur, depending on the interview – either way, the logo was undoubtedly a nod to Lagerfeld and Fendi’s inventive (if controversial) use of fur in ready-to-wear.

Evening ensemble

Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel, 1994-1997

Gift of Mrs. Alfred Bloomingdale

S2010.116.1A-D

Cocktail dress on display in Capturing the Catwalk (2018)

Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel, 1985

FIDM Museum Purchase: Funds generously donated by Barbara Bundy

2006.37.4

Of course, it was Lagerfeld’s time at Chanel that truly launched his name into fashion stardom and made him a celebrity in his own right. Thanks to Lagerfeld’s masterful reinvention, it’s often forgotten that the renowned French house struggled to find its footing after the death of its founder in 1971 – so much so that Lagerfeld claims he was warned against taking the helm of the then-tired and outdated brand when the position was offered to him. Yet he saw potential in Chanel’s ‘les elements eternels,’[8] the iconography associated with the house since its inception: tweed, quilted bags, the camellia, braided trim, chains, two-toned shoes, black and white, costume jewelry, and those quintessential interlocking C’s introduced by Madame Chanel herself. In the three and a half decades that followed Lagerfeld’s 1983 appointment, it became clear that his particular mix of impertinence, whimsy, and cultural awareness was the perfect answer to reviving the revered house. There is arguably no other designer who could have interpreted Chanel’s symbolism in a way that both honored and subverted its origins. As more young designers took the reins of venerated fashion houses throughout the 80s and 90s, inspiration from a brand’s history became expected – Tom Ford at Yves Saint Laurent, Alexander McQueen at Givenchy, John Galliano at Dior – yet it was Lagerfeld who perfected it and continued to exercise it (profitably) throughout his tenure. In his mind, “Tradition is something you have to handle carefully, because it can kill you. Respect was never creative.”[9]

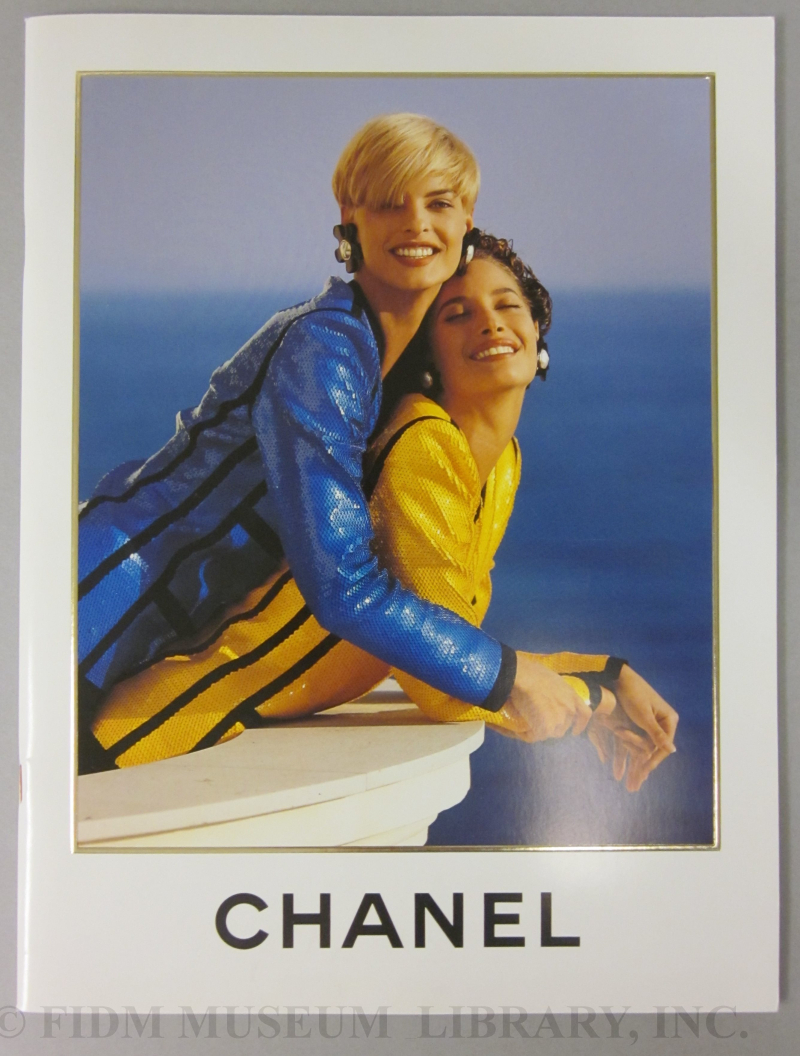

Chanel catalog

Chanel catalog

S/S 1991

Gift of Dorothy Washington Sorensen

SC2010.1110.416

Chanel catalog

Chanel catalog

F/W 2014-2015

Gift of Barbara Bundy

SC2014.37.5

Lagerfeld’s tactics successfully marketed the brand to a younger audience, who now clamored for anything with a Chanel logo. Lagerfeld’s street-style references included “punk, surfer, hip-hop, biker, and fetish fashions,”[10] all executed in the context of Chanel’s visual lexicon. He thoroughly embraced celebrity culture, and was an early adapter of technology – particularly social media. The over-the-top runway presentations, each more extravagant than the next, took advantage of the instantaneous dissemination of images on the internet.[11] The main hall of the Grand Palais was transformed completely into Chanel-branded supermarkets, carousels, airplanes, beaches, brasseries, icebergs, rocket ships – and for his final posthumous show, an alpine Swiss village. Nothing was too outlandish to capture the public’s attention.

Lagerfeld for Chanel accessories on display in Capturing the Catwalk (2018). From left: earrings, S/S 1988, FIDM Museum Purchase, 2005.5.68AB; bracelet, S/S 1933, Gift of Dorothy Washington Sorensen, 2010.1110.73; moon boots, F/W 1993-1994, FIDM Museum Purchase, 2014.5.49A-D.

That isn’t to say Lagerfeld did not respect the artistry and skill required of elite dress-making. His couture collections celebrated the talent of the house’s legendary ateliers. In the 1980s, under the subsidiary Paraffection, Chanel began purchasing several small Parisian métiers de couture to save them from extinction and continue the legacy of craftsmanship.[12] Lagerfeld then showcased the output of the workshops – dedicated to embroidery, featherwork, pleating, lace, millinery, jewelry, shoes, gloves, and more – in Chanel’s lavish Métiers d’Art fashion shows.

Evening jacket

S/S 1991

Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel

Gift of Linda & Steven Plochocki

2009.899.2

In the fast-paced world of fashion, Lagerfeld was one of the few designers immune to collection fatigue; at the time of his death he was still creating up to 14 collections per year for Fendi, Chanel, and his eponymous brand Karl Lagerfeld, which he launched in 1984. When asked how he was able to “to speak the languages of many different brands at the same time,”[13] Lagerfeld responded that each brand brought out different versions of his design instinct[14] – and as for creative exhaustion, he maintained that “ideas come to you when you work.”[15] On top of his fashion commitments, he pursued his passion for photography, often capturing his own advertising campaigns; decorated his homes in a succession of Art Deco, 18th century, and futuristic themes; and even wrote a diet book after his dramatic weight loss in 2001. Despite his unforgiving schedule, Lagerfeld never took his profession too seriously: “Please don’t say I work hard…Nobody is forced to do this job, and if they don’t like it they should do another one. People buy dresses to be happy, not to hear about somebody who suffered over a piece of taffeta.”[16]

Lagerfeld on the Karl Lagerfeld runway

Lagerfeld on the Karl Lagerfeld runway

F/W 1994-1995

Photograph by Michel Arnaud

Gift of Arnaud Associates, SC2000.1095.1

A self-described caricature, Lagerfeld was an active participant in the creation of his status as a fashion icon. The legacy he will leave the fashion world is unlike that of Balenciaga, Dior, or even Chanel herself. Instead, “he transformed the way in which fashion operates and the way in which people relate to it.”[17] Rather than introducing a revolutionary silhouette or design concept, he reimagined how the public could interface with fashion – and what they wanted from it. His designs consistently provided relevancy and status.[18] Lagerfeld moved forward relentlessly, always pursuing the next idea without expectation: “I have no idea of the future, never, ever. That’s what I like about fashion. It’s paradise now.”[19]

[1] Fraser Kennedy, “The Impresario: Imperial Splendors,” Vogue (Sept 1, 2004): 708-824.

[2] Andrew Bolton, “(Post)Modernity: Chanel and Lagerfeld,” Chanel (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005): 34-37.

[3] Kathleen Madden, “Vogue’s View: Lagerfeld: On His Own,” Vogue (May 1, 1984): 294.

[4] Vanessa Friedman, “Karl Lagerfeld, Designer Who Defined Luxury Fashion, Is Dead,” The New York Times (Feb 1, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/19/obituaries/karl-lagerfeld-dead.html

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Bolton, “Chanel and Lagerfeld,” Chanel , 34-37.

[8] Kennedy, “Imperial Splendors,” Vogue (Sept 1, 2004): 708-824.

[9] Madden, “Lagerfeld: On His Own,” Vogue (May 1, 1984): 294.

[10] Bolton, “Chanel and Lagerfeld,” Chanel , 34-37.

[11] Friedman, “Karl Lagerfeld,” The New York Times (Feb 1, 2019)

[12] Robin Mellery-Pratt, “Chanel, the Saviour of Savoir-Faire,” Business of Fashion (April 19, 2015): https://www.businessoffashion.com/community/voices/discussions/how-can-traditional-craftsmanship-survive-in-the-modern-world/chanel-saviour-savoir-faire

[13] Friedman, “Karl Lagerfeld,” The New York Times (Feb 1, 2019)

[14] Madden, “Lagerfeld: On His Own,” Vogue (May 1, 1984): 294.

[15] Friedman, “Karl Lagerfeld,” The New York Times (Feb 1, 2019)

[16] Ibid.

[17] Robin Givhan, “Karl Lagerfeld Didn’t Have a Signature Design – But He Invented a New Kind of Designer,” The Washington Post (Feb 19, 2019): https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/karl-lagerfeld-didnt-have-a-signature-design–but-he-invented-a-new-kind-of-designer/2019/02/19/334b4f9e-344c-11e9-854a-7a14d7fec96a_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.f040f6a0bc68

[18] Ibid.

[19] Kennedy, “Imperial Splendors,” Vogue (Sept 1, 2004): 708-824.