For our next two blog posts, Iesha Coppin-Forde takes us on a journey through the pages of Ebony magazine. Iesha was the FIDM Museum’s Lori and Sal Santamaura 2021 Summer Study Grant Digital Intern; she is a recent graduate of the School of Art and Design History and Theory at Parsons School of Design, where she received her MA in Fashion Studies with a pathway in Fashion Curation. She previously received her BBA in Fashion Merchandising and Publishing from LIM College. A significant component of her research is dedicated to the cultural analysis of fashion as dress and bodily practice. Her work interrogates the intersections of identity, memory, gender, and race embodied through the Afro-Caribbean experience and its intricate connections to martial and visual culture and design history. Iesha’s thoughts on her internship make us brim with pride:

Over the last several months, entering the virtual space hasn’t been the most effortless transition; from grad school to graduating over Zoom, it has become my “new normal.” A new normal which has created some fantastic opportunities, including a digital internship with FIDM Museum. My experience was both rewarding and fulfilling; guest lectures from industry professionals and online tutorials and training enriched projects which focused on my research interests, and honest communication centered around inclusion, diversity, and the overall future of museum practice. I can’t thank the staff at FIDM Museum enough for allowing me to become one of their first digital interns and recipient of the Lori and Sal Santamaura Summer Study Grant. I’m very much looking forward to the incredible work produced by future digital interns.

Thank you, Iesha, for enriching us!

PART I

“It was part of the politics of representation. It disturbed the ‘field of vision’ of its time.” 1

– Stuart Hall, 1984

Over the course of eight weeks, my research at The FIDM Museum offered greater insight into the personification of Blackness in America; from public awareness of race and visual representation to Black women’s integration into entertainment, fashion, and politics, the images proliferating the pages of Ebony magazine acted as a symbolic pillar that infiltrated popular culture. This post seeks to continue these significant and often fragmented conversations surrounding the ambiguity of black culture, black beauty, and resistance as a husband-and-wife duo altered the narrative of Black life in corporate America and beyond.

The Johnson Publishing Company: Imaging Ebony Magazine

Alan Barth, an American journalist, specializing in civil liberties, once said, “News is the only first rough draft of history.”2 This quote would reverberate throughout journalism during the mid-twentieth century, as publications such as The Saturday Evening Standard Post, Look Magazine, and Reader’s Digest were viewed as a staple of communication that focused on white America; a realization that motivated the introduction of Ebony Magazine.

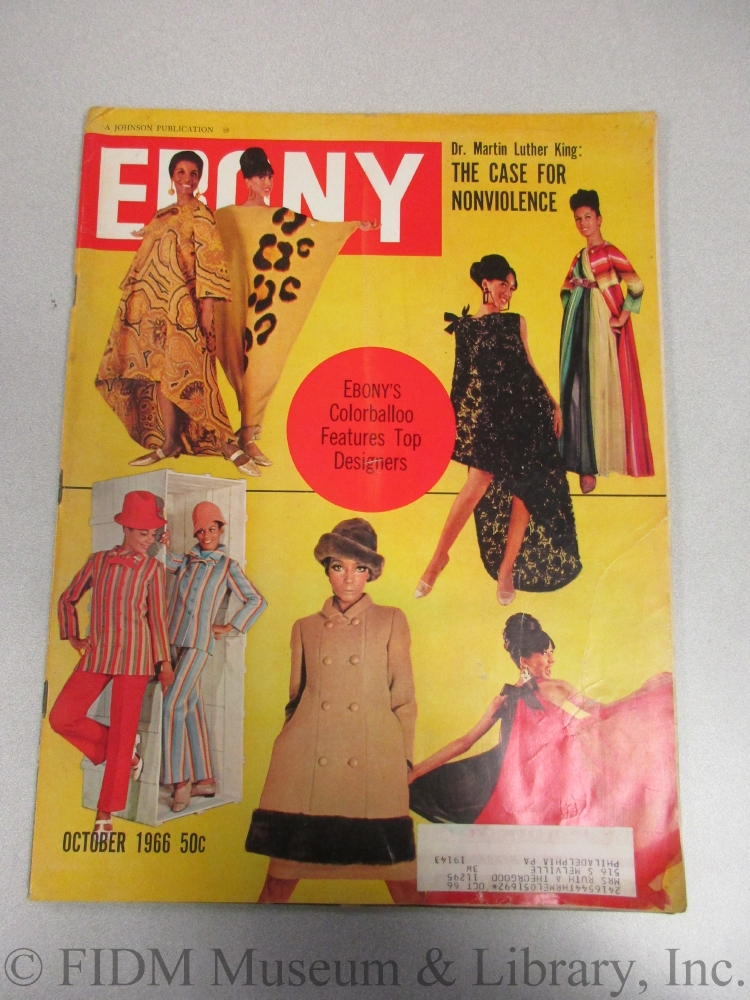

Considered a “love letter to the Black elite,”3 Ebony magazine, founded in 1945 by Chicago publishing mogul John H. Johnson anchored a positive and affirming dialogue for middle-class Black America, which echoed their tumultuous racialized history while also addressing their triumphant victories. When conceptualizing the famed African-American-focused magazine, John Johnson mentioned, Ebony “mirrored the happier side of Negro life—the positive everyday achievements from Harlem to Hollywood.” The highly coveted publication and its sister magazine, Jet, soon became a permanent fixture on the coffee tables of homes, beauty parlors, and barber shops, promoting a commodity for black culture while creating consumer culture within the black community.

According to a New York Times article by American author Brent Staples, Ebony magazine reached more than “40 percent of the nation’s black adults—a reach that was said to be unmatched by any other general-interest magazine in the country.”4 Ebony was modeled after white-owned publications such as Life magazine, amplified by its captivating photojournalism, becoming a blueprint for the Black-oriented publication. Johnson emphasized the use of photography in relation to Black historical matter, combating the racial articulations of Black life, portrayed through the lens of staff photographers Moneta Sleet Jr., G. Marshall Wilson, and Maurice Sorell.

When interpreting the essential purpose of image-making within the Black community, cultural critic and social activist bell hooks argues,

Access and mass appeal have historically made photography a powerful location for the construction of an oppositional black aesthetic. In the world before racial integration, there was a constant struggle on the part of black folks to create a counter-hegemonic world of images that would stand as visual resistance, challenging racist images.5

Staples reiterates the dehumanizing images that plagued Black America, as Johnson acknowledged a photographic publication capturing high-achieving African-Americans was both a lucrative venture and a way to advance Black claims of equal rights.6This ideology further indicated layered meanings into the Black experience through cultural nuances surrounding race, class, gender, power, and style. The Johnson Publishing company would expand its national reach through books, cosmetics, television, and radio, redefining the notion of blackness as a cultural conglomerate.

Hidden Figures: Eunice Johnson & The Crème Of Black Society

In 1958, Ebony introduced the Ebony Fashion Fair (1958 – 2009), what began as a charity event conceived by the wife of Dr. Albert W. Dent, president of Dillard University, to raise money for the Women’s Auxiliary of Flint-Goodridge Hospital in New Orleans, Louisiana, would later become the world’s largest traveling fashion show.7 When speaking to Veronica Jones, a fashion retail consultant and entrepreneurship coach for non-profit organization Custom Collaborative, Jones mentions the publicity surrounding the traveling fashion show,

“The Ebony Fashion Fair was publicized in all major Black newspapers. Virtually every large city in America with a significant African-American population had newspapers directed to the Black market, including The Philadelphia Tribune, The Pittsburgh Courier, The New York Amsterdam News, The New York Beacon, and The Crisis Magazine of the NAACP. We have a rich cultural history in this country that has been documented for us and by us.”

The Ebony Fashion Fair raised approximately $55 million, pouring back into the Black community funding civil rights groups, hospitals, community centers, sororities, and African-American-focused scholarships, while also enhancing sales and circulation of the publication. According to Audrey Smaltz, former fashion editor and sales coordinator for Ebony magazine, John Johnson gifted a 1-year subscription of Ebony and a 6-month subscription of Jet magazine to attendees of the fashion show, ultimately increasing readership and recognition. The Ebony Fashion Fair proved transformative images of African-American beauty, but its acclaimed success was not dependent on the consumer dollar, rather on the sartorial ingenuity of Eunice Johnson (1916 – 2010).

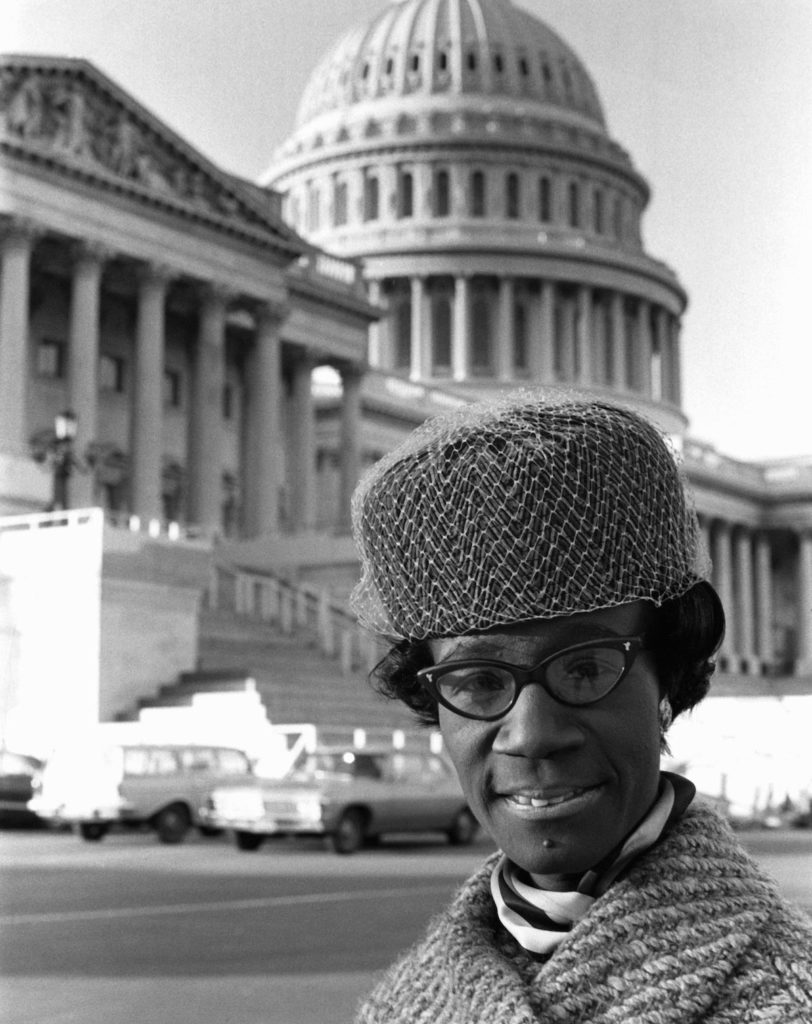

Before Eunice Johnson, wife of John Johnson, was appointed the visionary behind the Ebony Fashion Fair, her predecessor Freda DeKnight produced the show. Deknight was the first food editor for Ebony magazine, famously known for her column “A Date with a Dish.” Upon DeKnight’s passing in 1962, Eunice Johnson was allotted showrunner, where she provoked questions of classism and racism, challenging an unspoken “othering” often associated with the fashion and beauty industries.

In the words of Alex Abury, Director of the Fashion Resource Center at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Mrs. Johnson “changed the colour of fashion forever,”8 bringing haute couture and ready-to-wear to African-American audiences across the United States. Mrs. Johnson purchased an estimated 8,000 garments spending upwards of $1.5 million per year, which was often unheard of, especially for a woman of color. Her bespoke field of vision for both the glossy pages and the runway allowed the fashion industry to view the African-American community as a viable audience.9

Eunice Johnson’s sociopolitical mission to amplify blackness and radical cultural production drew audiences from coast to coast, as she reminded the Black community to boastfully take pride in themselves fueled by some of the most notable events in African-American history, including the March on Washington (1963), the establishment of the Black Panther Party (1966), and the “Black is Beautiful” movement (1960s – 1970s). The Ebony Fashion Fair toured over 200 cities nationwide on a greyhound bus with 11 models, outselling auditoriums in small-town America from the northeast to the segregated deep south as white supremacist group the Ku Klux Klan rallied outside their hotel.10 These discriminatory incidents did not discourage Mrs. Johnson, yet her multifaceted approach to the fashion industry as a producer, fashion director, editor, buyer, and writer allowed her to sew diasporic threads, essentially gaining international recognition that traced Canada, the Caribbean, and Europe.

Sources:

- Aubry, Alex. “Chronicles of chic: Mrs. Eunice Johnson,” System Magazine, System issue No.1, 156-167.

- Hall, Stuart. “Reconstruction Work: Images of Postwar Black Settlement [1984].” In Highmore, Ben (ed). The Everyday Life Reader. London and New York: Routledge, 2002, 262-272.

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia. “Bill Blass.” Encyclopedia Britannica, June 18, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bill-Blass.

- hooks, bell. “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” In Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. New York: The New Press, pp. 54-64.

- James, Frank. “Eunice Johnson Remembered For Linking Blacks, Fashion,” NPR, The Two-Way, January 5, 1-2. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2010/01/eunice_johnson_remembered_for.html

- Lewis D., Shawn. “Two Decades of Ebony Fashion Fair,” Ebony Magazine, December 1977, 146-148. https://books.google.com/books?id=7EJj7NQsAmYC&pg=PA146&dq=ebony+fashion+fair+Caribbean+spring+tour&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwifyqbUr73xAhU3l2oFHfcrCdkQ6AEwBnoECAoQAg#v=onepage&q=ebony%20fashion%20fair%20Caribbean%20spring%20tour&f=false

- Staples, Brent. “The Radical Blackness of Ebony Magazine: [Editorial].” New York Times, August 12, 2019, Late Edition (East Coast), pp. 1-4.

- Unknown. “Ebony Fashion Fair Opens Spring Tour in the Caribbean,” Jet Magazine, January 1980, 12-16.

- Unknown. “75 Years of Ebony Magazine,” Smithsonian National History Museum of African American History & Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/collection/75-years-ebony-magazine.

- Valenti, Lauren. “Naomi Campbell’s Guide to a Glamorous 10-Minute Beauty Routine,” Vogue Magazine, June 2020, 1-2.

End Notes:

- Stuart Hall. “Reconstruction Work: Images of Postwar Black Settlement [1984].” In Highmore, Ben (ed). The Everyday Life Reader. London and New York: Routledge, 2002, pp. 260.

- Staples, Brent. “The Radical Blackness of Ebony Magazine, New York Times, August 2019, 1.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- bell hooks. “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” In Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. New York: The New Press, pp. 57.

- Brent Staples. “The Radical Blackness of Ebony Magazine, New York Times, August 2019, 2.

- Shawn D. Lewis, “Two Decades of Ebony Fashion Fair,” Ebony Magazine, December 1977, 146-148.

- Alex Aubry. “Chronicles of chic: Mrs. Eunice Johnson,” System Magazine, System issue No.1, 156.

- Frank James. “Eunice Johnson Remembered For Linking Blacks, Fashion,” NPR, The Two-Way, January 5, 1-2.

- Aubry, Alex. “Chronicles of chic: Mrs. Eunice Johnson,” System Magazine, System issue No.1, 159.