Our most popular blog post of 2013 examines a clever Victorian accessory: the skirt lifter. Researched and written by summer intern Joanna Abijaoude, the post explores skirt lifters from a variety of perspectives. Thanks to Joanna for sharing her research on this object!

**********

Today's post was researched and written by FIDM Museum's summer intern Joanna Abijaoude. Over the past several weeks, Joanna has assisted with multiple projects, including digitizing ephemera from The Helen Larson Historic Fashion Collection and compiling research for an upcoming exhibition. Joanna is a 2014 M.A. candidate in the Visual Culture: Costume Studies M.A. program at New York University. In preparation for her thesis, she is researching Hollywood costume and 20th century designer Walter Plunkett. During her internship, Joanna became interested in skirt lifters, a distinctly Victorian accessory. In today's post, she explores the function, aesthetics, and cultural implications of a c. 1876 butterfly-motif skirt lifter in our collection.

**********

Though the Victorian era is well known for its ingenious inventions, this week I was introduced to a particularly clever gadget in the FIDM Museum’s Collection that served a practical sartorial purpose: the skirt lifter.

Skirt Lifter

Skirt Lifter

c. 1876

Museum Purchase

2007.5.18

A skirt lifter resembles a pair of small tongs, or scissors with padded circular discs instead of blades. The Museum’s example is brass and features a decorative butterfly that sits in between the handles. A small ring at the top would have held a cord, ribbon, or chain to suspend the tool just below the waist. Modern historians refer to the object as a “skirt lifter,” while period sources predominately use the term “dress holder.” When I initially encountered this object, several questions immediately came to mind: how was the dress holder incorporated into an ensemble and what occasions demanded its use? Did all classes of women utilize it? Why was the butterfly a popular decorative motif for this accessory?

Fortunately, the Museum’s dress holder gives us a helpful clue to start our research in the form of a patent date stamped on the side of the handle: October 16, 1876. In the later nineteenth century, more women participated in outdoor sporting hobbies such as promenading, croquet, and archery. An 1876 article in The Queen states “As the trains of outdoor dresses get longer and longer a serviceable dress holder becomes more and more indispensable.”1 Other dress holders were simpler and came in pairs to wear for cycling and similarly rigorous activities.2 There was also a resurgence of the polonaise dress during this period, an ensemble consisting of an overdress gathered up in elegant drapes to expose a decorative petticoat – a look that referenced the eighteenth century robe à la polonaise. The skirt lifter both pulled the dress up to avoid soiling the hem and created the fashionable gathered drapes of the polonaise. According to The Atlanta Constitution, dress holders were worn “suspended from the right,”3 as seen in these two fashion plates:

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, 1870

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, 1870

Peterson’s Magazine, June 1879

Peterson’s Magazine, June 1879

Fashion scholar C. Willet Cunnington suggests dress holders were worn as early as 1846 to pull the dress up while walking,4 but the trend reached its peak of popularity from the 1860s to the 1880s. As promenading and other outdoor pursuits became stylish, the tool was “much used by the elegantes to raise the trains of their walking dresses,”5 making skirt lifters a definitive fashion statement. Apparently, though, it was not a universally admired accessory, as Godey’s Lady’s Book called the dress holder “useful but not pretty.”6 Other cord and loop mechanisms were employed to pull the dress into folds, but many of these were hidden under the skirt, or disguised by ribbons and bows. The skirt lifter was the most visible and decorative accessory used for this purpose. It could be worn on its own, or as one of the multiple tools dangling from a chatelaine, an ornamental belt with chains and clasps to hold a lady’s various accoutrements: fan, parasol, eyeglasses, sewing scissors.7

Chatelaine dress holders and belt clasps featured in The Queen, October 14, 1876

Chatelaine dress holders and belt clasps featured in The Queen, October 14, 1876

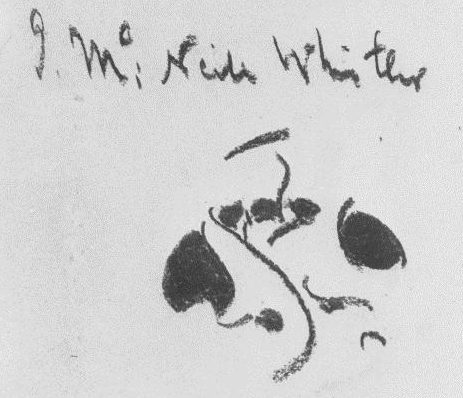

We now know who wore the dress holder and why, so let’s turn our attention to the charmingly detailed butterfly that covers the handles. The FIDM Museum’s dress holder was made in 1876 during the height of the Aesthetic movement, which eschewed the mass produced goods of industrialism in favor of artistic ideals and quality craftsmanship – “art for art’s sake.”8 The butterfly represents Aestheticism’s embrace of Asian design influences, so much so that the renowned painter James Whistler, a major proponent of this artistic movement, created a signature monogram with his initials stylized into a butterfly.9 Though this skirt lifter was mass produced, the manufacturer was marketing its products according to the fashionable motifs of the era.

Butterfly embroidery featured in La Mode Illustrée, February 21, 1875

Butterfly embroidery featured in La Mode Illustrée, February 21, 1875

James Whistler, “Butterfly Monogram,” Charcoal on paper The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 23.230.8

With this one lovely accessory, we have gleaned information about the sartorial, social, and cultural trends of the mid-to-late nineteenth century. It represents women’s progression out of the home and into the public sphere, and as their participation in outdoor recreation continued to grow, their desire to elegantly adapt fashion for physical activity was met by this dress holder.

1 Ardern Holt, The Queen, November 1876.

2 Genevieve E. Cummins and Nerylla D. Taunton, Chatelaines: Utility to Glorious Extravagance (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club Ltd., 1994), 161.

4 C. Willet Cunnington, English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century (London: Faber & Faber, 1937), 145.

5 Le Follet, “Fashions for August,” The Manchester Guardian, July 29, 1876.

6 “Chitchat on Fashions for September,” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine, September 1878.

7 Cummins and Taunton, Chatelaines, 160.

8 David Jaffee, “America Comes of Age: 1876-1900,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007), http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/amer/hd_amer.htm.

9 Barbara H. Weinberg, “James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903),” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010), http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/whis/hd_whis.htm.