In today's post, Christina Johnson, associate curator and resident photography expert, describes her long-standing fascination with historic photography. She also discusses the conservation of a mid-nineteenth century ambrotype portraying two dashing urban gentleman. In previous posts, Christina has explained how photography can be used to understand fashion history. You can find her two-part series on that topic here and here.

Ambrotype

Ambrotype

Probably United States

c. 1855-60

Glass, leather, silk velvet, metal & wood

Gift of Steven Porterfield

2010.897.25

I’ve studied fashion history since I was a little girl. When I was a teenager, I discovered my grandmother had two antique trunks jam-packed with old photographs—literally thousands of portrait photographs—dating from the 1850s to the 1950s. Grandma had inherited them from her sister-in-law, who had methodically asked for old family photos anytime a relative, however distant, died. Everyone ended up handing over all their heirloom photos to Aunt Marjorie. I spent hours poring over them, organizing and dating them by what people were wearing. They taught me fashion history. I loved looking at peoples’ clothes and their faces. I wanted to know their stories.

I became more interested in the technical side of these images in college and graduate school. My dorm room always had a pile of library books on daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, wet-plate collodion plates, and gelatin silver images right next to my towering stack of fashion books. When I started working at the FIDM Museum, I decided to found a historic photograph collection. The Museum now collects portrait photographs that clearly show people in fashionable attire. Not only are they displayed in exhibitions like Fabulous! Ten Years of FIDM Museum Acquisitions, 2000-2010, staff also use them to aid in styling mannequins.

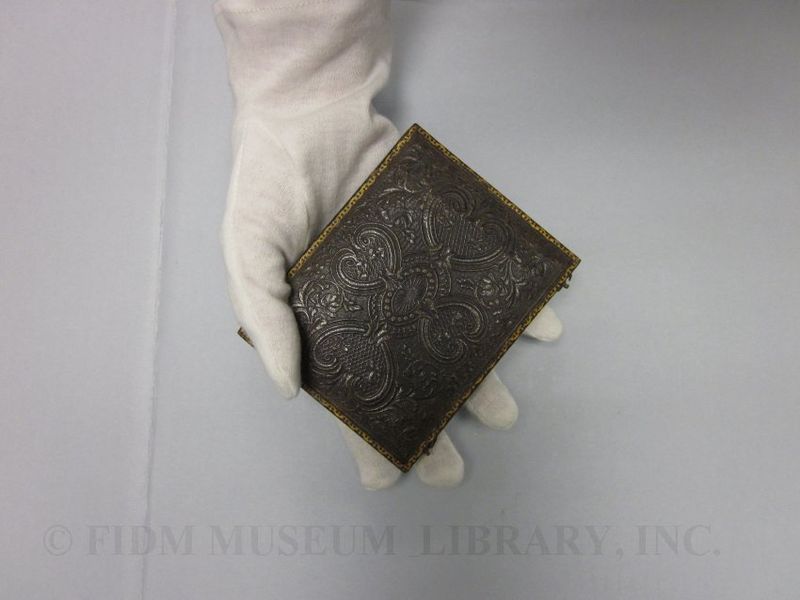

The tooled leather case of our ambrotype looks like a small, ornately decorated book.

The tooled leather case of our ambrotype looks like a small, ornately decorated book.

An ambrotype is an image that is fixed on a delicate plate of chemical-treated glass. The image can easily be smudged and scratched, even after development, so a metal mat and cover glass was placed over it and packaged together into a hard case – usually tooled leather over wood—that looks very much like a miniature book. The case holding the ambrotype of our two gentleman is pictured above.

Ambrotype before conservation. Notice the yellow lines, which indicate cracked emulsion.

Ambrotype before conservation. Notice the yellow lines, which indicate cracked emulsion.

This ambrotype was offered to the Museum as a donation. Unfortunately, it was in fair-to-poor condition when it arrived, as you can see from the image above. We generally only accept donations in very good or excellent condition because conservation can be a very expensive undertaking. We made an exception for these two fashionable gents, whose personality seemed to shine through cracked emulsion, grime, and corrosion. We knew we would be including a man’s c. 1860 frock suit ensemble in the FABULOUS! catalogue, and this would be the perfect supporting image. We sent it to conservators at The Better Image studio who cleaned and stabilized the piece, as well as filled-in the cracks with archival black pigment.

Ambrotype after conservation. The difference is remarkable!

Ambrotype after conservation. The difference is remarkable!

This ambrotype dates from about 1855-60, when the process was most popular. It was a simpler and cheaper process than the previous photographic method, the daguerreotype, which required liquid silver and many intricate sensitizing steps. This example was most likely made in the United States, which led the way in scientific improvements to photographic methods and industrial standardization of needed supplies. Commercial portrait studios were found in every American city by the mid-nineteenth century.

City living was a grimy endeavor. These two sitters wear the male uniform of civility: dark wool suits that masked soot belching from factory smokestacks or dust clouds raised by horse-driven omnibuses. They tilted their top hats to the rakish angle worn by the era’s “fast young men,” or “sports”— 1850s terms for “dandies.” Self-presentation was a serious matter for these fellows. Wide bowties were a fad, paired with broad, turndown collars, worn in the second half of the 1850s.The man on the left holds a narrow walking stick—likely meant to aid a calculated strut down the street, not to lean on heavily due to a limp. These friends even opted to pay a little extra to have their cheeks highlighted with light pink pigment and their watch chains tinged with gold. I wonder what they were thinking about when they faced the camera lens.

yes, it’s nice to see this post!

I do similar photo analyzing at our library in the history files, using “fashion” to narrow down the dates for unknown gatherings. Around this part of the Midwest we didn’t have many dandies, mostly worn-out farmers with families, a few high-minded ladies of town, and the odd scoundrel. Nothing like a good portrait to add depth (or cancel out rumors) for a person or tradition.

Beautiful conservation of image. Keep up the good work.

Thomas