For the next two weeks, we’ll be featuring posts from our extensive blog archives. Today’s post was written by Meghan Hansen, FIDM Museum Registrar, in 2009. In this post, she dives into our fragrance archive with an investigation into a counterfeit Chanel No. 5 box and bottle.

**********

“Bathtub Perfume Traps Pool Shark”1 “Pair Arrested in Sale of 11c Perfume for $15”2

These headlines suggest the rampant problem of piracy in the perfume industry, a criminal activity prevalent in any field in which luxury goods are involved. For an example of the legal battles that can ensue from the selling of pirated fashions, check out this New York Times blog post. Though Chanel’s fragrances were not the only French perfumes targeted by counterfeiters, Chanel No. 5 consistently turns up in smuggling arrests, counterfeit busts, and consumer warnings about cheap perfume scams. Chanel No. 5 has a cachet that everyone wants, but where does this reputation come from?

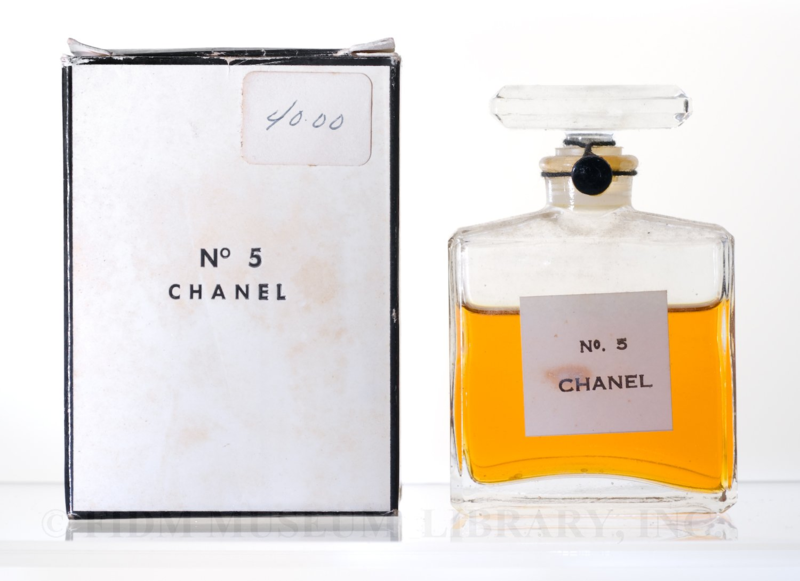

Counterfeit Chanel No. 5 Bottle and Box

Counterfeit Chanel No. 5 Bottle and Box

c. 1950-1959

Gift of Annette Green

F2005.860.986AB

This perfume bottle and packaging, from the Annette Green Perfume Archive at the FIDM Museum, is an example of the persistent copying of Coco Chanel’s famous perfume. While Chanel’s distinctive suit has been imitated since its creation, by the House of Chanel’s own designer Karl Lagerfeld as well as many other designers, the box and bottle above are examples of criminal counterfeiting. For more on Coco Chanel’s design legacy, take a look at this recent article.

No. 5 Bottle

No. 5 Bottle

Chanel

c. 1960-1969

Gift of Annette Green

F2005.860.856

When Chanel No. 5 was released in 1921, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel became the first couturier [a high-end custom clothing maker who belongs to the French Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture Parisienne] to make her name world-renowned through a signature fragrance. With unmistakable synthetic ingredients and modern packaging, Chanel No. 5 became the most recognizable fragrance on the market. The fame of Chanel No. 5 began with its scent, the first to make bold use of synthetic aldehydes. Today Chanel No. 5 is part of the lexicon of fragrance that pervades American culture, but in 1921 it was an entirely novel smell.

The packaging design for No. 5 reflects the emerging ideas of modernity of the early 1920s. While perfume-making was not Coco Chanel’s specialization, the packaging design for No. 5 fit nicely into her fashion design repertoire. Chanel chose a man’s toiletry bottle, square and simple in shape, as the basis for the Chanel No. 5 bottle. Between 1921 and the present, only slight modifications have been made to the proportions of the bottle.

No. 5 Boxes

No. 5 Boxes

Chanel

c. 1957

Gift of Annette Green

F2005.860.1009AB

Similarly, the simple rectangular cardboard boxes of white with black borders have remained nearly the same since the 1920s. When first introduced, the exterior packaging referenced men’s suiting with two narrow pinstripes across the front, like in her fashion design. Later, the pinstripes were removed, giving the packaging still further simplicity. Following the decadent bottle and packaging designs of the belle époque, Chanel’s simplicity was extraordinary. The sparse black and white gave Chanel No. 5 a distinction and elegance that became much desired.

No. 5 Bottle and Box

No. 5 Bottle and Box

Chanel

c. 1930-1959

Gift of Annette Green

F2005.860.981AB

This simplicity lent No. 5 an ease of manufacture that other high-end fragrances could not achieve with their hand-painted labels, intricately molded bottles, and tassel bedecked cardboard boxes. With the straightforwardness of manufacture came the attendant effortlessness for copyists. They could easily procure white boxes and square bottles on which to print counterfeit labels in black ink. In the case of the FIDM Museum’s counterfeit example (first image), neither bottle label nor box text includes “Paris” where it would normally be printed in large font to emphasize the French origin of the product. The bottle is slightly out of proportion and its label is clearly typewritten, exhibiting clear indentations where the typewriter striking head came in contact with the paper. Finally, the box is slightly narrow in comparison to authentic Chanel No. 5 boxes in the collection. All this evidence adds up to a greater mystery: Where did the counterfeit bottle and box come from? Who made it and who bought it?

1 “Bathtub Perfume Traps Pool Shark” New York Times 6 Dec. 1958, p. 25.

2 “Pair Arrested in Sale of 11c Perfume for $15” New York Times 9 July 1965, p. 33.

An interesting post posing intriguing questions. Of course it fits in with other areas in the arts – where it has been estimated that 30% of master painters’ works in the marketplace are forgeries, with a likely comparable in museum collections. I have personally noticed forgeries in costume design sketches for iconic stars and costume designers. And they sold at outrageous prices!